How Sharing Data Drives Supply Chain Innovation

In the late 1980s, Mike Graen of Procter & Gamble Co. moved to Arkansas to work on the company's Walmart team. At that time, Walmart was P&G's fifth largest customer, and data sharing and collaboration between suppliers and retailers was in its infancy. Graen was charged with improving the economics between the two companies using information technology. According to Graen, "Within the first eight months, we made a $50 million swing in profitability [in terms of Walmart's profitability selling our product]."

Before this change, the only thing that P&G knew about its product demand was that another order for a truckload had arrived. Graen called this level of data sharing and collaboration a "whole new world," which he attributed to the ability to see -- for the first time -- inventory levels, store-level sales data, and everything from when P&G shipped an item to Walmart to when it was sold at the register.

The legendary story of how Walmart profited from data sharing and how it improved logistics through better forecasting and inventory management is well understood; however, it has not been replicated to the same level by any other retailer to date. This can be attributed to the genius of Sam Walton, a Big Data analytics pioneer. By taking it to the next level, the information sharing had a network effect, as Walmart expanded its data sharing from P&G to every supplier that wanted in. As Tom Muccio, P&G's president of Global Customer Teams, who began collaborating with Walmart in 1987, said, "We had the ability to invent the future."

An Innovation Magnet

This whole new world of data sharing and collaboration not only improved forecasting and marketing, but also created new points of competition between suppliers within Walmart's growing supply chain. In the early 1990s, Walmart formalized its Retail Link system, which provided sales data -- by item, store and day -- to all of its suppliers. This information translated to lower merchandising cost for Walmart, and also saved suppliers time and expense in planning their production and distribution. The surprising side benefit to Walmart and its customers was that each of its suppliers also competed with each other to make Walmart smarter, allowing Walmart to pass on the savings.

For example, Supplier X might argue that Walmart should dedicate more shelf space to its products because of its high sales volume and high profit margin. Supplier Y would then crunch the numbers and argue that reducing shelf space of its brand might not seem so negative on its face, but that shoppers of its product also often buy additional products that carry high margins for Walmart. While Supplier X and Supplier Y jockeyed back and forth, providing greater insight with each analysis, Walmart gained a wealth of understanding about what was going on in the business. Each brought an alternative approach to forecasting, estimated their own and cross-price elasticity and shelf out-of-stock rates, calculated store and DC fill rates, analyzed assortment decisions, estimated inventory investment and cost analyses, derived return on investment for the shelf space, and illuminated category trends and its drivers.

With so much competition for new and improved insights, new analyses were routinely conceived and birthed. With access to so much data at such a granular level came the need for careful data cleansing and also possible calculations that pushed analytical skills and creativity to their limits.

Walmart itself did not possess the resources to develop focused analyses on a given product because it carried hundreds of thousands of products. But its suppliers did because they had relatively small sets of products and significant vested interest in seeing those products' performances optimized. In addition, the suppliers were the experts on their categories and end consumers. Walmart was an expert on its stores and retail business.

These analyses became increasingly insightful as suppliers placed analytical and creative people on teams working with Walmart because the opportunities for improvements and the strategic value of the competition with other suppliers were greater there than at other retailers who did not provide the information and/or engage in collaboration. Thus, when Walmart began sharing its data, it did more than take the noise out of forecasting for suppliers;it became a magnet attracting innovators to a place where new ideas would be continuously developed and improved to everyone's benefit. (It is well known that, when it comes to demand, forecasting, order and shipment data have significantly more noise than point-of-sale data.)

A Culture of Collaboration

Innovations introduced first at Walmart reverberated throughout the retail/consumer goods industry,but Walmart and its suppliers benefitted first. (Actually, these innovations have reached other industries as well. Companies from many other industries have studied this collaboration and information sharing.) By the time its echoes reached the competition, the next phase of advancement had already been made at Walmart.

This data collaboration effect was a culture of innovation, progress and entrepreneurship among Walmart suppliers in northwest Arkansas. Companies brought their best people from all over the world to tap the potential of information systems and its impact on the retail business. The networks of creative individuals who understood the opportunities and challenges associated with analysis of data clustered together; this resulted in intense competition and innovation in Walmart's supply chain ecosystem.

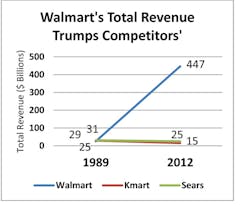

Keep in mind, when Walmart first started sharing this data in 1989, it was a company with about $25 billion in annual revenue. Sears and Kmart were bigger retail competitors, at $31 billion and $29 billion, respectively. Walmart was not the largest retailer in terms of revenue and even its largest suppliers had significant brand equity over them (consider at that time P&G's relative strength with consumers).

The question that begs to be asked, then, is, "Why didn't more retailers follow Walmart's lead in regards to data sharing, in order to spur innovations within supply chain ecosystems?" It clearly wasn't for lack of size, but more likely a lack of understanding and strategic thinking regarding Big Data analytics. The graph below demonstrates Walmart's astronomical growth pattern over Sears and Kmart.

A Change in Retail Culture

The tactical benefit of sharing information was to improve forecasting and reduce the bullwhip effect, creating more efficient supply chain networks and improved merchandizing. (The bullwhip effect is a description of the phenomenon that uncertainty in demand grows with information that is available at higher nodes in the supply chain. When analyzing point-of-sale data, a more accurate forecast of demand is generated than when analyzing shipment data to retailers.)

The strategic benefit was that sharing its data made Walmart the place where suppliers competed to innovate. Other retailers are now beginning to share information and this is the future of success in retail -- innovation and insightful analysis, not negotiation. Any retailer can hire great negotiators, but creating a culture of innovation and collaboration takes strategic thinking and analytical capabilities.

Because of the benefits of data sharing to retailers and suppliers, Adam Smith's invisible hand will be at work and other retailers will increasingly adopt similar practices. Many of those retailers that do not adopt data sharing and collaborative practices risk going out of business. Similarly, a number of lesser-known retailers will come into prominence.

Listed below are five trends in retail data sharing and collaboration that we will see over the next 10 years.

- Data democratization: Resulting in even more open innovation and improving efficiency of the entire retail/consumer goods supply chain.

- Data harmonization: Integrating data from many different sources including retailer (point-of-sale), supplier, syndicated, sensor, customer sentiment, pricing, and promotional data, as well as internal shipping and invoicing data, which will drive new business insights, higher margins, decreased costs, and improved data accuracy.

- Data innovation: Fostering improved internal/external collaboration with a shift in focus on increasing the pie and creating new market niches.

- Data condensation: Providing focus on foresight for specific opportunities in pricing, assortment, inventory management, new product introductions, etc.

- Data learning: Creating algorithms to provide continuous improvement in analysis from multiple sources of data, where the output becomes input, curating actionable decisions thru adaptive learning systems and data-driven analytics.

Lessons Learned from Walmart

Current and future retailers would be wise to look to Walmart for lessons on knowing their suppliers and shoppers to grow their business. Three things retailers of all size can learn from Walmart are:

- Collaboration drives innovation, where shoppers, retailers and suppliers all benefit from sharing data and creating a central point of truth.

- Innovation occurs when there is healthy competition between and among suppliers in the supply chain ecosystem.

- In turn, retailers and suppliers can gain insight by working with trusted third-party partners who can leverage data sciences to provide foresight for early action. These early actions reduce cost of merchandising, make supply chains more efficient, and cultivate enduring shopper loyalty.

Matt Waller is chair of Orchestro Science Network and chief data scientist of Orchestro. He is also professor & Garrison Endowed Chair, Walton College, University of Arkansas. PV Boccasam is CEO of Orchestro.