Though the U.S. machinery industries have struggled of late with a strong dollar, sluggish global growth and political uncertainty, exports in the sector are poised for growth in the medium term. But first, the next few years will be more of the same.

Two trends lead economist Jeremy Leonard of Oxford Economics to the forecast: the investment cycle and demographics.

First, he notes that the U.S. is at a weak point in the machinery investment cycle, due to a very slow U.S. recovery. “The question is whether or not it’s going to pick up strongly or not strongly,” he says. “We tend to be of the view that investment will be fairly weak into the next couple of years.”

However, pent up demand, especially in Europe—which has been slowed by “crisis-upon-crisis” including the sovereign debt crisis, Brexit, immigration, etc.--eventually will give way to a global pick-up in investment. “We’re actually pretty bullish by European standards on investment over the next four to five years, precisely because investment has been so weak for the last five to six years,” Leonard explains.

As well, the recent slowdown in emerging markets is likely to dampen demand for U.S. exports in the near term, but these markets “are expected to be a key source of growth over the longer term,” according to an HSBC report based on Oxford Economics data.

China’s investment trends are likely to run counter, Leonard adds, as “we’ve seen a structural deceleration of investment demand in China.”

“Different regions have different things going on, but broadly speaking, there are pockets of strength looking ahead in machinery demand,” he concludes.

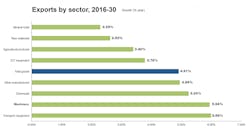

Overall, Oxford Economics/HSBC forecasts that the machinery sector will grow 5.9% per year from 2016 to 2030, and that it will contribute nearly 27% of the projected increase in total U.S. merchandise exports from 2016 to 2020, then 24.7% from 2021 to 2039.

The second trend, he asserts, will have a more significant impact, because it has to do with how things will be produced as the working age population declines throughout the industrialized world and slows elsewhere. “Because you have a working age population that is getting smaller, that’s going to push up wages, and therefore companies will, to the extent they can, try to become more capital intensive,” Leonard says. “That’s a big part of what’s driving what we think are pretty bullish forecasts on machinery and equipment exports and production generally as we look ahead.”

“It’s a mega-trend that’s going to continue for the next 10 to 15 years, and nothing can really stop it,” Leonard adds, noting that it applies to other emerging markets. “It’s not just a developed world story.”

“Paradoxically, even with China moving to become a more consumer-oriented or domestically focused economy, its production is going to have to become more capital intensive because of this demographic shift.”

The Impact of a Strong US dollar

The high value of the U.S. dollar will continue to bedevil U.S. exporters for the next one or two years, but Leonard says history suggests machinery manufacturers can—and will--adjust. He recalls a similar situation in the early 2000s: “After the dollar had strengthened, there was a reaction in the manufacturing sector to become more competitive, to cut costs and, as part of that, to invest in additional equipment and machinery, as well as in reorganizing how you do things with ERP and lean manufacturing, etc. So in a sense, there’s a response to this competitiveness shock.”

He adds: “U.S. manufacturers have typically been able to implement the kinds of things they need to do, to become cost competitive. So we think that’s going to happen. So, even if the dollar were to stay about where it is, and not weaken, we would argue that you would still see an improvement in trade prospects for US exporters.”

The HSBC report indicates similar optimism: “Exports are also expected to recover as—despite the strong U.S. dollar—the U.S. economy is still globally competitive thanks to high productivity, moderate wage growth, the benefits of a stable regulatory environment and low energy costs.”

Sub-Sector Strengths

Overall, Leonard says, U.S. export growth will be led, as it always has been, by high-tech, high-value-added machinery and precision equipment, which requires expertise and engineering know-how that is only present in a handful of countries.

The machine tool sector is the best example, Leonard says. Combining the facts that 90% of the market is dominated by four countries—Germany, U.S., Japan and Korea—and that such highly engineered machinery is becoming more and more critical to all kinds of manufacturing, U.S. manufacturers stand to see increased export demand.

Another is specialized machinery, such as food processing equipment. “Again, they require a certain amount of fault tolerance, a certain level of quality and reliability, and engineering know-how embedded in them,” says Leonard. That means developed countries such as the U.S. have a significant competitive advantage over countries like China, India and Vietnam.

The energy industry also is expected to see a turnaround, according to HSBC and others. Innovations in drilling and infrastructure investments have spurred a new era in energy exports, according to recent report by IndustryWeek. Leonard points out that that can mean new investment in specialized fracking and deep water drilling machinery and equipment.

Meanwhile, construction is coming off a bit of a glut driven by big stimulus packages in China that drove “massive demand over a short period of time,” Leonard says. “So looking out further, to the extent that construction in China may not be expanding at the pace that we saw since the end of the financial crisis, the potential for export there might be diminished.”

Export Highs and Lows in Perspective

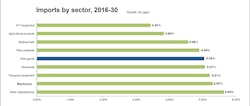

That said, the trade balance in the machinery sector is likely to stay close to balance due to strong imports of the less-value added products within the sector, according to Oxford Economics/HSBC projections.

Leonard explains that this results because many sub-sectors within machinery are not as high-value added, requiring less engineering know-how to design and manufacture. A simple example is a machine-tool bit, but other examples include conveyor belts, material handling, winches and other standardized tools on factory equipment “where the designs are simpler or somewhat commoditized by industry standards,” Leonard says.

In these markets, Leonard adds, “emerging markets are starting to have an impact on trade, because they do now have the engineering expertise, which is less than for the specialized machinery, and they are putting it to use and taking advantage of some of their cost advantage.”

Another reason is the complex global supply chains, in which U.S. companies export components to a lower-cost country for assembly into a final product, which is imported back into the U.S.

As for the trade balance dropping in recent years, Leonard insists on some perspective. “Yes, there’s been a decline,” he admits. “But this came after a very, very significant increase in the 2000s.” When the decline started in 2011, machinery exports, he points out, “were at a historically high level.”

Cliff Waldman, chief economist at Washington D.C.-based MAPI, agrees: “With machinery--high-tech, high R&D machinery--we have a relative balance with the rest of the world,” he says. “We’d like to see the surplus, but the balance is pretty good, it’s pretty competitive.”

“Even with this rough patch we’ve had since the great recession, machinery has been keeping manufacturing growth above water. And I think in the future, once we get through this rough, slow, strained patch, machinery is going to push us forward, it’s going to continue to be a growth leader.”

About the Author

Patricia Panchak

Patricia Panchak, Former Editor-in-Chief

Focus: Competitiveness & Public Policy

Call: 216-931-9252

Follow on Twitter: @PPanchakIW

In her commentary and reporting for IndustryWeek, Editor-in-Chief Patricia Panchak covers world-class manufacturing industry strategies, best practices and public policy issues that affect manufacturers’ competitiveness. She delivers news and analysis—and reports the trends--in tax, trade and labor policy; federal, state and local government agencies and programs; and judicial, executive and legislative actions. As well, she shares case studies about how manufacturing executives can capitalize on the latest best practices to cut costs, boost productivity and increase profits.

As editor, she directs the strategic development of all IW editorial products, including the magazine, IndustryWeek.com, research and information products, and executive conferences.

An award-winning editor, Panchak received the 2004 Jesse H. Neal Business Journalism Award for Signed Commentary and helped her staff earn the 2004 Neal Award for Subject-Related Series. She also has earned the American Business Media’s Midwest Award for Editorial Courage and Integrity.

Patricia holds bachelor’s degrees in Journalism and English from Bowling Green State University and a master’s degree in Journalism from Ohio University’s E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. She lives in Cleveland Hts., Ohio, with her family.