The United States needs progress on climate change, Dow (IW 500/22) CEO Andrew Liveris told a manufacturing conference recently, but he wasn't talking about reducing greenhouse gases. He was describing the business climate in the U.S. and the problem of "complex and expensive regulations stifling America."

"Dow has over 60 agencies monitoring it," he said. "I'm sure I could do with 50, or 30."

Manufacturing leaders such as Liveris are quick to point out that they are not against all regulations, but they argue that companies are increasingly confronted by a complex array of regulations that impose ever higher costs on U.S. producers. At a time when the nation needs to strengthen its competitiveness, they warn, regulations instead result in unintended consequences such as lower productivity, less employment, fewer exports and less innovation.

See Also: Global Manufacturing Economy Trends & Analysis

"No single regulation or regulatory activity is going to deter innovation by itself, just like no single pebble is going to affect a stream. But if you throw in enough small pebbles, you can dam up the stream," says Michael Mandel, an economist with the Progressive Policy Institute. "Similarly, add enough rules, regulations and requirements, and suddenly innovation begins to look a lot less attractive."

"I can attest that poorly designed regulations and duplicative or unnecessary paperwork requirements create real costs that affect manufacturers' bottom lines," Drew Greenblatt, the president and owner of Marlin Steel Wire Products, testified before a House subcommittee on Feb. 28.

As an example, he related how the company, with 32 employees and $5 million in sales in 2012, had received a letter in 2010 from the Treasury Department imposing a $15,000 fine because Marlin Steel Wire omitted "a third signature on a 20-page form when we created a 401(k) plan for our employees." After several weeks of communication, the company eventually paid a smaller penalty, but Greenblatt said "valuable resources were diverted away from our business activities because of a missed signature on a form."

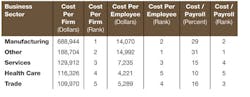

While federal regulations pose a challenge even for large companies, they can be particularly daunting for smaller firms and especially burdensome on small manufacturers. A 2010 study by the U.S. Small Business Administration's Office of Advocacy found that regulatory costs averaged $8,086 per employee for all companies. But for all manufacturers, the average cost was $14,070 per employee. For manufacturers with 20 or fewer employees, the study found the average cost was $28,316 per employee.

Picking Up the Pace?

When asked what the top challenges facing the Obama administration and the Congress were, 76.4% of executives told the NAM/IndustryWeek Survey of Manufacturers last December that the burden of government regulations needed to be reduced.

Since 1981, the federal government has issued 2,183 regulations affecting manufacturing, according to a study by NERA Economic Consulting commissioned by the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI). Of that total, 235 are considered "major" regulations, with compliance costs of $100 million or more. The study estimates that these regulations cost the economy from $265 billion to $726 billion a year in direct compliance costs.

The study also warned that the pace of regulation is picking up. It noted that the Clinton administration issued an average of 36 major regulations annually, the Bush administration averaged 45, and the Obama administration is averaging 72 major regulations each year.

Just in January, according to the American Action Forum, the federal government added $12 billion in costs and nearly 12 million hours of paperwork burden. In February, the group warned, rules such as the transparency report final rules under the Affordable Care Act and EPA regional haze requirements could add $15.8 billion in cost burdens. At that rate, AAF estimated, the government could add $138 billion in regulatory costs in 2013.

While business groups have warned that the Obama administration is unleashing a regulatory "tsunami," the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) has called it more of a "soft wave." The group analyzed data from the OMB's Office of Information and Regulatory Analysis (OIRA) and found that in the first 42 months of each administration, the Bush administration in its first term published 1,060 final rules, compared to 1,771 in the first Clinton term and 1,002 in the first Obama term.

The center found that the Obama administration had indeed issued more significant regulations but that nearly half (97 of 200) were required by legislation or judicial order. And it noted that because of the lengthy rulemaking process, many regulations extend over several administrations.

For example, EPA's greenhouse gas rule was first proposed in 1999. In 2003, the Bush administration's EPA refused to issue a finding of endangerment to the public, which would have required rulemaking under the Clean Air Act. In 2007, the Supreme Court overruled the EPA decision and a subsequent ruling by a federal appeals court required EPA to make another determination. In 2009, the Obama EPA ruled that greenhouse gases endangered public health. EPA then issued two economically significant regulations implementing the ruling.

Is Better Regulation Ahead?

In his "state of manufacturing" speech February 13, NAM President and CEO Jay Timmons complained that the "regulators in Washington are unchecked, imposing new costs and additional uncertainty on manufacturers."

Timmons said regulations should be based on "sound science" and regulators should be forced to "weigh the costs of regulations against the actual benefits rather than against speculative or imaginary gains."

In his 2011 State of the Union Address, President Obama, like a number of his predecessors, promised to fix "rules that put an unnecessary burden on businesses." On Jan. 18, 2011, he issued Executive Order 13563, which instructed federal agencies to develop plans to "facilitate the periodic review of existing significant regulations" and modify or repeal rules found to be ineffective or excessively burdensome.

Michael Greenstone, a professor of Environmental Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, called Obama's requirement that agencies routinely revisit the costs and benefits of regulations "a revolutionary step in the right direction" and urged that these reviews be legislatively mandated. He also called for the creation of a body similar to the Congressional Budget Office that would allow the legislative branch to conduct independent, objective reviews of regulations.

Hal Quinn, president of the National Mining Association, gives the president credit for issuing EO 13563, but he says the results are another matter.

"After a year, out of a $1.75 trillion burden, all these agencies were able to identify was $10 billion of regulatory burden they could eliminate over five years. That is one-half of 1% of the entire burden," said Quinn. "That was a really underwhelming, unimpressive result and raises concerns about the urgency and seriousness given to this issue."

Federal agencies have typically estimated that the benefits of regulations exceed the costs by a factor of 10, says Susan Dudley, a former OIRA director and now director of George Washington University's Regulatory Studies Center. And she notes there is considerable uncertainty built into these estimates. Pointing to a recent OIRA estimate of total regulatory benefits, she said more than 90% of the benefits were attributed to EPA rules to reduce air particulates.

"The uncertainty of those benefits is huge," she said. "In fact, the uncertainty is so huge that the benefits could be zero, because we don't know if exposure to particulate matter causes the consequences EPA is estimating."

Business groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce say one way to bring more order and accountability to the regulatory process would be through passage of the Regulatory Accountability Act. Among other things, that bill called for more attention to cost-benefit analysis in rulemaking and expanded opportunities for public challenges to rules. In the last Congress, the bill (HR 3010) passed the House but died in committee in the Senate.

The Center for Effective Government's Katherine McFate charged the bill was a "backdoor way for conservatives to prevent the implementation and enforcement of decades of public protections -- without actually having to vote against the Clean Air Act or the Clean Water Act."

But as the nation's regulatory burden grows, some believe the system needs more radical change to prevent the rules of the road from driving the economy off a cliff. One idea floated by Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., is to require agencies to retire an old regulation in order to implement a new one.

If fixing the regulatory system is controversial, the cumulative impact of regulation is certain. And that leaves experts like GW's Dudley asking, "How is it that every year we need 40 major $100 million, sometimes $1 billion, regulations? Were things working so badly one year ago, five years ago, that we're always thinking up ways to constrain the markets?"

About the Author

Steve Minter

Steve Minter, Executive Editor

Focus: Leadership, Global Economy, Energy

Call: 216-931-9281

Follow on Twitter: @SgMinterIW

An award-winning editor, Executive Editor Steve Minter covers leadership, global economic and trade issues and energy, tackling subject matter ranging from CEO profiles and leadership theories to economic trends and energy policy. As well, he supervises content development for editorial products including the magazine, IndustryWeek.com, research and information products, and conferences.

Before joining the IW staff, Steve was publisher and editorial director of Penton Media’s EHS Today, where he was instrumental in the development of the Champions of Safety and America’s Safest Companies recognition programs.

Steve received his B.A. in English from Oberlin College. He is married and has two adult children.