A Cost-Effective Approach to Maximizing International Intellectual Property Protection

International competition is increasing daily. Competitors are nimble and quick to copy, and customers are demanding and looking for the best price. Brand name and personal relationships still carry some weight, but not as in years past. One way for U.S. manufacturers to compete effectively in today's marketplace is by controlling innovation through intellectual property ("IP"). Given the international nature of business, IP protection should also be international and, to the extent cost effective, coextensive with a business' current and future market presence.

We suggest a three-step approach to creating an international IP portfolio. First, regardless of location, always utilize contracts and trade secrets with employees and business partners, such as suppliers, distributors and contractors. Second, if practical, use patents to both (i) fortify the protection provided by contracts and trade secrets, and (ii) protect your technology from entities with which you have no contractual relationship. Third, select the countries in which you desire patent protection, which are usually those in which your products are sold or will be sold, and then implement your IP strategy.

Below we explain the IP protection mechanisms, how to select the countries in which patent protection should be obtained, and two case studies that apply these principles.

(1) The IP Protection Mechanisms: Contracts, Trade Secrets and Patents.

(a) Contracts: Whether or not your technology is protected by a patent, it may still be protected by contract. Contracts should always be used with employees and your direct business partners, such as suppliers, distributors and contractors. Contractual protection may even be suitable for customers (for example, if you already enter into contracts with customers to sell industrial machinery.)

The contracts should require your employees and business partners to (i) maintain the confidentiality of business information (such as your technology, designs, marketing plans, costs, selling prices, and the identity of vendors and customers), (ii) not compete with you during the term of the contract and for a reasonable period of time (usually one to five years) thereafter, and (iii) assign improvements to your technology to you.

You can usually select the law that governs a contract and the locale for resolving contract disputes. Select the law of one of the United States that is likely to uphold the contract's provisions (particularly the non-compete clause) and require any dispute to be resolved in a U.S. court or in arbitration in the U.S. If your employee or business partner is outside of the U.S., check with an attorney in the country where your employee or business partner is located to ensure the contract provisions are enforceable there.

The costs to enter into contracts are the legal fees associated with preparing and negotiating them. Depending on a contract's complexity and the length of negotiations, plan on about $3,000 - $10,000 per contract with each business partner. The costs for employee contracts are usually negligible.

(b) Trade Secrets: A trade secret is information that both: (1) derives actual or potential economic value from not being generally known and not being readily ascertainable to others by proper means, and (2) is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy. Trade secrets cost nothing to obtain, although maintaining them requires some expense because each person or business exposed to the trade secret should execute a contract with an appropriate confidentiality provision (also called a non-disclosure provision).

Here, all persons and businesses that executed contracts in the preceding Section (a) would be bound to maintain the confidentiality of your business information. By using contracts and other reasonable efforts to maintain the secrecy of your information, trade secret protection protects against the misappropriation of your information by anyone, even persons with whom you have no contractual relationship. That is the added benefit of trade secrets as compared to contracts.

Information that cannot be maintained as a secret includes (1) publicly-available product designs, and (2) things that can be reverse engineered, such as (i) internal components that can be discovered through disassembly of a product, and (ii) material compositions that can be ascertained through laboratory analysis.

Trade secrets have at least one advantage over patents. In many countries, including the U.S., trade secret life is potentially indefinite whereas a patent's life is typically 20 years from the original patent application filing date.

A major disadvantage of trade secrets is that they do not protect against independent development by a competitor, whereas patents do. Further, once a trade secret has been disclosed to numerous people, even with the proper confidentiality agreements in place, it can be misappropriated without you knowing who was responsible.

(c) Patents: If practical for your technology, patents are usually the strongest, most valuable and most expensive component of your IP protection. Business buyers often place a high premium on patents if the patents are prepared to provide a broad scope of protection.

Here, we explain what a patent protects, the costs of obtaining international patents in selected jurisdictions, patent application filing scenarios commonly used by U.S. businesses, and how to select the most cost-effective approach given your circumstances.

(i) What a Patent Protects

A patent protects the functional, or utilitarian, aspects of a new product, machine, process or method, or composition of matter (such as a chemical or pharmaceutical compound).3 Patents are the only practical IP protection against entities with which you have no contractual relationship if your product can be readily copied, because it could not be protected as a trade secret. Patents also protect against independent development by another. A competitor need not even know of your patent to infringe it.

(ii) Typical Costs for Patent Protection in Selected Jurisdictions

The following Charts A and B show, respectively, typical costs in selected jurisdictions for filing patent applications and obtaining patents for a relatively standard application having 20 pages, ten drawing pages, and 23 claims.

With very few exceptions, international patent applications are based upon the original U.S. utility application prepared by your U.S. attorney, so the application preparation fee is a one-time cost. Here that cost is estimated in Chart A under the column for U.S. attorney and in the row for the United States at $12,000 (the additional $600 is the cost for preparing transmittal documents and filing the U.S. application).

The costs in Chart B related to obtaining a patent include the filing costs from Chart A. The additional costs in Chart B are for prosecution of the patent application and payment of a governmental issue fee once a patent is granted. Prosecution is the process by which an application, after being filed, advances through the patent office. Prosecution culminates when your application either matures into a patent, is finally rejected with no chance of further prosecution, or is abandoned by you.

The typical time to obtain a patent is three to five years from the application filing date and the costs are usually front-end loaded. For instance, in the example above the initial preparation and filing cost for a U.S. application is $13,690, which is 62% of the total cost of $21,940 to obtain the patent.

| Chart A: Typical Costs for Filing Patent Applications in Selected Jurisdictions | ||||

| Governmental and (if applicable) Foreign Attorney Fees | Translation | U.S. Attorney | Total | |

| United States | $1,090 | $0 | $12,600 | $13,690 |

| PCT | $3,462 | $0 | $600 | $4,062 |

| Australia | $1,943 | $0 | $600 | $2,543 |

| Brazil | $1,257 | $1,650 | $600 | $3,507 |

| Canada | $1,543 | $0 | $600 | $2,143 |

| China | $1,180 | $2,149 | $600 | $3,929 |

| France | $2,061 | $3,380 | $600 | $6,041 |

| Germany | $1,585 | $3,803 | $600 | $5,988 |

| Japan | $2,332 | $5,342 | $600 | $8,274 |

| Mexico | $2,678 | $1,690 | $600 | $4,968 |

| Spain | $1,905 | $2,746 | $600 | $5,251 |

| United Kingdom | $1,668 | $0 | $600 | $2,268 |

| European Patent Office | $8,677 | $0 | $600 | $9,277 |

| Chart B: Typical Costs for Obtaining Patents in Selected Jurisdictions | ||||

| Governmental and (if applicable) Foreign Attorney Fees | Translation | U.S. Attorney | Total | |

| United States | $2,940 | $0 | $19,000 | $21,940 |

| Australia | $3,376 | $0 | $6,000 | $9,376 |

| Brazil | $3,114 | $1,650 | $6,000 | $10,764 |

| Canada | $3,185 | $0 | $6,000 | $9,185 |

| China | $1,924 | $2,149 | $7,500 | $11,573 |

| France | $3,569 | $3,380 | $5,500 | $12,449 |

| Germany | $2,740 | $3,803 | $6,500 | $13,043 |

| Japan | $6,594 | $5,342 | $9,000 | $20,936 |

| Mexico | $3,093 | $1,690 | $7,000 | $11,783 |

| Spain | $4,913 | $2,746 | $6,000 | $13,659 |

| United Kingdom | $2,554 | $0 | $6,000 | $8,554 |

| European Patent Office | $12,549 | $4,788 | $9,000 | $26,337 |

(iii) Typical Patent Filing Scenarios for U.S. Businesses

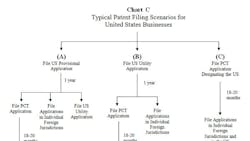

Your filing scenario should be chosen to: (1) not potentially harm your patent rights, and (2) be as cost effective as possible, particularly by providing you with time and sufficient information to determine whether to incur the costs of filing applications in individual foreign jurisdictions. Selecting the proper filing scenario requires a basic understanding of U.S. utility applications, U.S. provisional applications, PCT applications and EPO applications, which are discussed below.

U.S. Utility Applications and U.S. Provisional Applications

In Chart C, filing scenarios (A) and (B) are similar, except that scenario (A) begins with a U.S. provisional application and scenario (B) begins with a U.S. utility application. There are significant differences between the two. A U.S. utility application is prosecuted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office ("USPTO") and can ultimately mature into a U.S. patent. During prosecution a search report with pre-existing patents and patent applications (collectively called "prior art") is issued. This prior art helps you determine whether you will ultimately obtain a patent, the scope of available patent protection, and hence whether you should incur the costs of filing applications in individual foreign jurisdictions.

A U.S. provisional patent application, on the other hand, can never mature into a patent, is not prosecuted or examined and no search report is issued for it. The purpose of a provisional application is to buy additional time (up to twelve months) to file a U.S. utility application that can claim "priority" to the provisional application, which means that the effective filing date of the utility application is the filing date of the provisional application. Priority, however, can only be established if the provisional application contains a complete description of your invention. If the provisional application is hastily prepared as a rough draft, which many are, it likely will not provide adequate support for a priority claim by your U.S. utility application. Moreover, once you file a provisional application the clock starts running for foreign filing and at the end of the twelve-month provisional application period you must file foreign applications in individual foreign jurisdictions and/or a PCT application. Some foreign jurisdictions, such as the EPO, have more stringent priority rules than the U.S. and if your provisional application has no claims and lacks multiple, specific examples of your invention, which frequently is the case, it would not support a foreign priority claim.

Some file provisional applications to buy twelve months to asses the market acceptance of a product before incurring the costs of filing a U.S. utility application. This strategy has questionable merit. First, as noted above, a sketchy provisional application may not support either a later-filed U.S. utility application or foreign application. Second, any potential buyer of your invention would almost certainly ask to review your patent application to determine its strength. An incomplete provisional would not suffice.

A short U.S. provisional application should only be used when there is not time to prepare a full U.S. utility application. Such an instance would be if you plan to publicly disclose your invention within a day and need to file some type of application to avoid losing the opportunity to pursue patent protection in some foreign jurisdictions. If faced with that situation, file a U.S. utility application claiming priority to the provisional as soon as possible.

The Benefits of a PCT Application

In Charts A, B and C, "PCT" means "Patent Cooperation Treaty." A PCT application never matures into a patent and is a mechanism to buy about 18-20 months of extra time before incurring the costs of filing patent applications in foreign countries.10 That extra time is what makes a PCT application valuable because during that time you (i) defer the costs of filing applications in individual foreign countries, (ii) may obtain outside funding, (iii) determine the invention is not economically viable, or (iv) learn of prior art that would prevent you from obtaining a patent or greatly limit the scope of patent protection. Although a PCT application ultimately adds about $4,000 to $5,500 (depending upon the length of the application) in expense to the overall patent application process, most businesses use the PCT process because of the extra time it provides.

If a PCT application is filed after your U.S. utility application, as we recommend, your U.S. utility application will have been pending for at least 30 months before you must file patent applications in individual foreign jurisdictions. During that 30-month period you will receive a prior art search in your PCT application and likely will have received the prior art search in your U.S. utility application.

A PCT application should not be used if the filing costs in individual foreign jurisdictions are less than or just slightly more than the cost of the PCT application, because then there would be no potential cost savings. For example, if you only plan to foreign file in Canada, which costs $2,143, or in Canada and Australia, which cost a combined $4,686, the cost is less than or just slightly more than a PCT application (which costs $4,062) and the benefits of the PCT are negated or minimal.

The Benefits of an EPO Application

"European Patent Office" or "EPO" means a patent application filed in, and a patent issued by, the European Patent Office. An EPO patent can potentially provide protection in up to 38 European countries, which makes it relatively inexpensive given the number of countries that can be covered. What many people do not realize is that once an EPO patent is granted (for the estimated $26,337 figure noted above in Chart B) it must still be registered and maintained in every European country in which you would like protection. That can significantly add to the overall EPO costs, but in the final analysis, with an EPO application, you have only a single filing fee, no translation fees during filing or prosecution, and just one set of patent prosecution fees. As a rule of thumb, if you seek patent protection in four or more European countries, an EPO patent will likely be more cost effective than obtaining patents in individual countries.

Comparing the Filing Scenarios: Usually Filing Scenario (B) with the PCT Sub-Option is Optimal

Referring to Chart C, in most cases filing scenario (B), with the PCT sub-option, wherein a U.S. utility application is filed first, is preferred. This scenario provides the full benefit of the extra time provided by the PCT application and you would have 30-32 months from your U.S. utility application filing date before you must file applications in individual foreign countries. During that time you will obtain the PCT search and likely obtain the USPTO search. With this information you can better ascertain the odds of obtaining a patent and the probable scope of patent protection. You would also have the maximum time in which to evaluate your invention, and obtain market feedback and studies on the invention's economic viability. With this information you could better decide whether or not to incur the costs of filing in individual foreign jurisdictions.

Under filing scenario (A) with the PCT sub-option,14 if you first file a provisional application and then file both a U.S. utility application and a PCT application twelve months later, you would only have 18-20 months until individual applications must be filed in foreign countries. During that time you would receive the search from the PCT application, but would likely not receive the USPTO search, and have less information on which to base your decision to file in foreign jurisdictions.

Filing scenario (C) is not often used because it also minimizes the advantage of using the PCT application to buy extra time. Using scenario (C), you again would have only 18-20 months to gather information and, as with filing scenario (A), potentially not have the benefit of the USPTO search.

(2) Determining the Countries in Which to Obtain IP Protection.

Rely on contractual protection for your employees and business partners, regardless of location. Trade secret protection requires no filings or registrations, but to maintain the trade secret in even one country, you should enter into a contract that includes confidentiality provisions with each person or entity throughout the world that would be exposed to the trade secret.

If you plan to also rely on patent protection, it is only necessary to obtain patents in those countries where you sell or realistically plan to sell your products, because a patent prevents others from making, using, importing, offering to sell or selling products or services falling within the scope of the patent, regardless of the origin of the products or services. For example, if the markets for your product are the United States, Canada and Australia, and your competitors are in China and India, it is not necessary to obtain patents in China and India. Proper patent protection in the United States, Canada and Australia would prevent your competitors from legally selling infringing products in those countries and thus protect your markets.

(3) Developing a Cost-Effective Strategy Based on Your Scenario.

Case Studies A and B, below, apply the principles of Sections (1) and (2):

Case Study A

You sell automotive parts. The parts can be readily reverse engineered and cannot realistically be protected other than by patents, although you consider some techniques about the manufacturing and your customers to be confidential. You sell the parts primarily in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Spain, Belgium and Austria. You plan to enter markets throughout the remainder of Western Europe and potentially in Japan. You will have the parts manufactured in China and sold through distributors in each country in which you conduct or plan to conduct business.

First, enter into a contract with employees and each business partner, including suppliers (e.g., your Chinese manufacturer) and distributors (one in each country in which you sell the parts). Each contract should include confidentiality, non-compete and assignment of improvements provisions, and be governed by the law of a state within the U.S. that is likely to enforce the contract's provisions. Any contract dispute should be resolved in the U.S. Check with an attorney in each country where employees, suppliers or distributors are located to ensure the contract provisions are enforceable there.

Second, patents are the only viable protection against entities other than your contract partners. For this case study, assume there is no reason (such as an impending public disclosure of your invention) to file a U.S. provisional application. Therefore, you file a U.S. utility application in accordance with filing scenario (B), above. If it costs $12,000 to prepare the original U.S. utility application, your costs in year one would be $13,690 total to prepare and file the U.S. utility application.

Twelve months after filing your U.S. utility application, you would file a PCT application. Because you are conducting business in six European countries, an EPO application is likely the most cost-effective approach to cover the European countries. You would thus designate at least Canada, the EPO and Japan in your PCT application, and the cost of filing the PCT application would be about $4,062.18

At about 20-24 months after filing your U.S. utility application, you should receive an office action from the USPTO and search results listing prior art.

At 30-32 months after filing your U.S. utility application, which is 18-20 months after filing your PCT application, the PCT process is complete and you must determine whether or not to file in individual foreign jurisdictions. By this time you would have prior art from the PCT application and should have prior art from the U.S. utility application. With this information you can better determine the odds of obtaining a patent and the likely scope of patent protection. You should also have market feedback about your invention and internal information about the invention's economical viability. In this case, assume that all information is positive and you file patent applications in Canada, the EPO and Japan, for a total cost of about $19,694.

Over the next three years, plan on further prosecution and issue fee costs in the U.S., Canada, the EPO and Japan of about $45,000. Your total costs in this case study to obtain patent protection would be about $82,000 over a period of about 5 1/2 years. Contracts for nine business partners would cost an estimated $4,000 each, or about $36,000. Therefore, the total costs for IP protection would be about $118,000 spread over about 5 1/2 years.

A benefit of filing scenario (B) with the PCT sub-option is that, if the information had been negative, the cost of foreign filing and prosecution in Canada, the EPO and Japan could have been avoided, and you could have abandoned the U.S. utility application. In that case, the total costs related to patents would have been capped at about $20,000. Your only IP protection would be contracts and trade secrets, but better to spend only $20,000 before learning that no meaningful patent protection was available than to move forward with incomplete information (for example, if you had not had the search from the U.S. utility application) and spend another $19,694 to file in individual foreign jurisdictions.

Case Study B

You sell a chemical with ingredients that cannot be easily reverse engineered because they undergo a change during processing, and some key ingredients are present in miniscule, virtually undetectable amounts. One key ingredient is a little-known plant constituent from Central America that has never been used before in chemicals of the type you sell. Your manufacturing process is extremely valuable. You have discovered that the process temperature, method of agitation and rate of cooling after agitation lead to a vastly improved product. You are confident that your competitors are unaware of these parameters. You also believe it would be difficult or impossible to determine if a competitor has copied your process based on an analysis of the competitor's product.

You sell the chemical through distributors in the United States, Canada and Japan, and have large potential markets in Brazil, Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom. You manufacture in the United States and your gross profit margin is 70%, but you could increase it to 85% by manufacturing in Taiwan, India or China.

First, as with Case Study A, enter into appropriate contracts with employees and all business partners. Given the nature of your technology, you may not want to move manufacturing to Taiwan, India or China because secrecy is important to protecting your IP and long-term profits.

Second, in this case you likely would not want to use patent protection unless you believe that a competitor will soon discover your chemical formula and manufacturing parameters. If you prepare and file patent applications, those will ultimately be published and provide a road map teaching your competitors how to manufacture your chemical. Instead of patents, rely on your contracts and trade secret protection. Also, do not ship the rare plant material directly to any contract manufacturer regardless of where the manufacturer is located. Instead, have the plant material shipped to you in plain packages or in packages labeled with your company's name. Then (legally) remove all indicia of the original origin of the plant constituent if you plan to re-ship it to an outside manufacturer, or re-package the constituent before shipping. You could also mix it with another constituent prior to shipping to further conceal its identity.

From a practical standpoint, do not treat contracts with confidentiality provisions as a panacea. The fewer people that know your formula or process, and the less they know, the more likely you can maintain your formula and process as valuable trade secrets.

The total costs to maintain IP protection under this case study would be the cost of entering into contracts, which would likely be about $4,000 per contract for seven contracts, or about $28,000, plus the cost of conducting business in a manner to preserve the secrecy of your technology. The more people and businesses potentially exposed to your technology, the more costly that endeavor.

Conclusion

International IP protection is imperative for U.S. manufacturers that cannot, or do not wish to, compete in commodity manufacturing and are looking for effective ways to increase their bottom line. Using the approach outlined here, always enter into contracts (that, among other things, protect your trade secrets) with employees and business partners. Then, determine whether your technology should be protected in the general marketplace by patents. If so, determine the countries in which you desire patent protection and implement your IP protection strategy.

David E. Rogers is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Squire, Sanders & Dempsey L.L.P. http://www.ssd.com/ Amy L. Hartzer is President of IsoPatent, LLC http://www.isopatent.com/