American Workers: Caught in the Jaws of Change

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

The 1987 report from the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment predicted: “During the next two decades, new technologies, rapid increases in foreign trade and the tastes and values of a new generation of Americans are likely to reshape virtually every product, every service and every job in the U.S. These forces will shake the foundations of the most secure American businesses”

Well, it has been 35 years since the report, and the prediction has come true beyond imagination. Outsourcing, free trade agreements, the flood of foreign imports, the dependence on China and the rise of inequality have created massive change—particularly for American workers.

The Reduction of Labor Costs

In the early 1980s, U.S. corporations adopted a program of “restructuring,” which included reorganization to decrease cost and outsourcing jobs to foreign countries. The restructuring also included a big investment in automation, which began to eliminate blue-collar jobs. The introduction of personal computers and the internet also gave corporations the opportunity to eliminate millions of white-collar jobs. Only recently has there been some recognition from corporations of what this has done to the middle class

This was the beginning of a period where U.S. workers’ compensation would not keep up with the growth in productivity. After 1980, wages and household income began to decline or stagnate for most of the middle class. The poor wage growth of American workers was a failure by design driven by the multinational corporations and their shareholders. As research from the Economic Policy Institute recently documented, wage suppression “was generated by policy choices that resulted in excessive unemployment, eroded unionization, corporate globalization, lower labor standards (e.g., lower minimum wage), new imposed contract terms (e.g., noncompete) and corporate structure changes that pushed down wages and profits in supply chains to the benefit of large firms.” As a result, wages have stagnated or fallen, while corporate profits and CEO salaries have reached new heights.

The Creation of Economic Deserts and Crumbling Cities

During the 20th century, America built thousands of manufacturing plants in small towns in the Midwest. When these plants were built, whole communities formed around them, providing good paying jobs for millions of people without college degrees—as well as jobs at all of their supplier companies and the merchants in the communities.

Things began to change for these communities in the 1980s, when American corporations began to outsource production and re-engineer their organizations to adapt to globalization. But, at the turn of the new century, two things happened that would seal the fate of many of these communities. The Chinese were allowed into the World Trade Organization and the NAFTA Agreement went into effect. These changes led to the devastation of many towns and smaller cities, such as Danville, Virginia; Dayton, Ohio; Newton, Iowa; Bruceton, Tennesse; Flint, Michigan; Johnstown, Pennsylvania; Galesburg, Illinois; Youngstown, Ohio; Muncie, Indiana and many more.

Migration to Service-Industry Jobs

According to an economic analysis by Jeff Ferry, an economist at the Coalition For Prosperous America, most of these people had to take jobs in the service industries, and their standard of living declined. According to the CPA survey, most of the non-supervisory, laid-off workers found jobs in in leisure and hospitality (bars, coffee shops, restaurants and hotels), social assistance and education services, for lower pay and fewer hours. The CPA survey estimates that laid-off manufacturing workers suffered a 19.2% fall in their standard of living, and many of the service jobs offer little or no benefits.

The Persistence Of The China Shock

Research presented at a Brookings Institution conference in 2021 says that of 722 U.S. regions analyzed, 223 of them, or 32.9%, suffered absolute declines in per capita income. This means that “the open door for Chinese imports reduced the incomes of one third of the U.S. public.”

The Big Shift In Wealth

During the 2012 Presidential election, Republican Mitt Romney railed against Democrats and Socialists whom he said wanted to redistribute the nation’s wealth and income. What he didn’t mention is that wealth and income had already been redistributed, and he was one of the recipients.

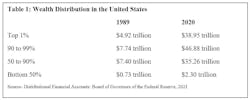

Table 1 below shows that in 2020 the top 10% of households had $85.83 trillion in wealth, and the other 90% had $37.56 trillion. But the most startling number is at the bottom: 50% of households had only $2.30 trillion, or 2% of the total wealth.

This comes at a time when 46.7 million citizens are below the poverty level. Nobel Prize in economics winner Joseph Stiglitz, in a 2015 oped article, said, “America is becoming a more divided society – divided not only between whites and African Americans, but also between the 1% and the rest, and between the highly educated and the less educated, regardless of race. The median income of a full-time male employee is lower than it was 40 years ago. Wages of male high school graduates have plummeted by some 19%”.

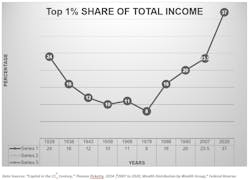

Another way to look at the big picture is to go back to 1929, when 1% of the wealthiest people had 24% of the total income of the country. At the end of that year, the nation fell into the Great Depression. The government answer was the New Deal, where tax rates went up to 90% on the very rich and laws and legislation favored the average worker.

The effects of the New Deal lasted until 1978, when the 1% had only 8% of total income. But then laws and legislation changed in favor of the wealthy again, and they began to grow their share of income. By 2007, they were back to where they left off in 1929, and by 2020 they had 37% of the total income of the nation.

I don’t think that the average American begrudges the top 1% their income gains. What they resent is that the growth for the top 1% has come at the expense of everyone else.

In the late 1970s, when wages began to stagnate, the middle class tried to keep up their buying power by women going to work, working longer hours, drawing down savings and going into debt. But for many in the middle class, these coping mechanisms have been exhausted and no longer work.

Yes, we are now in the Post-Industrial Economy, and the assumption that living standards will improve from one generation to the next is in question. There is no simple answer for why the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. A combination of events—including outsourcing, the trade deficit, tax reduction, the decline of unions, and a concerted effort to reduce labor costs by multinational corporations—all have contributed to the acceleration of inequality and the enormous gains in wealth by the top 1%.

If you are part of the top 10%, life is good, and you’re probably interested in supporting legislation that maintains your position. But if you are in the middle or lower class—or if you are one of the 83 million (56%) of all workers who do not have a college education—then the future probably looks bleak.

The society that was built from the New Deal—that propelled the middle class—has virtually ended. These changes have put much of the middle class into a precarious position and there is a general unrest in the country.

A White Voter Backlash...

A report by professors at McGill and Georgetown universities shows that “white voters in the U.S. associate manufacturing job losses with the loss of upward mobility and a broader American decline.” The authors say that “this problem is predominantly an economic problem facing white, high-school-educated Americans who have been left behind in the post-industrial service economy.” I think this is true and makes these people vulnerable and susceptible to populism, conspiracy theories and scapegoats.

The majority of these changes and the shift in wealth and resulting inequality has been driven by the multinational corporations and their policy decisions since 1980. In 2019, they made a pledge to do better for all of their stakeholders, which I think means for their workers, families, communities and suppliers. So, the question is will they be willing to do something about these problems? It is time for them to step up to the plate and offer some solutions

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.