China Saw Opportunity in the Panama Canal as US Interest Dwindled

Part I of Two-Part Series: Read Part II: Trump, China and the Panama Canal

During the 2024 campaign at his many rallies, Donald Trump almost always mentioned the United States’ construction of the Panama Canal as evidence of the past U.S. greatness.

President-elect Trump’s recent pronouncements on the Panama Canal—and China’s role in the canal’s operations—have brought a renewed focus on the “path between the seas.”

Before exploring what might happen during the second Trump Administration concerning the Canal, it would be best to understand how we got to now.

A Canal Built for War

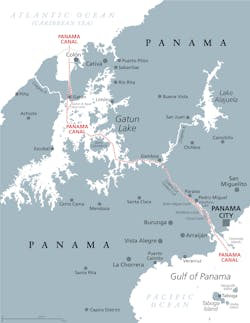

1903-1914: President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated with the new nation of Panama the right to build and fortify the Canal on a 10-mile strip of land through Panama. Roosevelt used the military argument to lobby Congress to build the Canal, arguing that it would allow the U.S. Navy to move between the Atlantic and Pacific in a matter of a few hours rather than the several weeks needed via the Straits of Magellan.

1914: The Canal is completed. Over 1,000 merchant ships pass through that year. Nonetheless, an obscure German academic, correctly identified that the political importance of the Canal was greater than its economic value. It was not built by the Americans principally as a trade route but as an instrument of war. Zadow saw the building of the canal as a serious setback for Japan, allowing Americans to fully exploit Hawaii as their base of naval operations. “The possession of the Hawaii Islands is equivalent to the mastery of the Pacific” and would cause conflict with Japan, Zadow wrote, more than 20 years before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

WWII and Postwar Era: the Canal’s Shift from Military to Commerce

Paradoxically, World War II would ultimately reduce the Canal to an auxiliary status of both the U.S. Navy and America’s global ambitions. As aircraft carriers got bigger and bigger during and post-World War II, the Canal simply could not handle them. The locks were too small.

1950s: Driven by the strategic goal of deploying more and more carrier groups, America had developed a multi-ocean fleet navy: the opposite of what Teddy Roosevelt originally envisioned. The biggest single reason the Americans built the Canal in the first place was moot in less than 30 years. The Canal was now merely an auxiliary of the U.S Navy.

World War II also transformed the United States economy and solidified for all time the strength of both coasts, further reducing the need for the Canal. The full industrialization of the Western United States, along with the greater integration of America’s transcontinental railroads and the new Interstate Highway System, diminished the relevance of the Canal to both the U.S. government and the American economy.

As historian Bruce Cummings observed, after the war “the Pacific States and much of the West were independent: in oil, steel, factories, and investment capital.” As the years went on, the Canal had less and less to do with all this.

The U.S. Looks for an Exit

The post-War era saw leaders on both sides the political aisle looking for an exit out of Panama. The U.S. lost more money every year operating it. Further, the continued presence of America’s Canal Zone in the middle of sovereign Panama made it harder for U.S. foreign policy to argue against imperialism by the Soviet Union and its satellites.

President Harry Truman, who rarely held back on sharing his thoughts, said, “Why don’t we get out of Panama gracefully, before we are kicked out? In 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower observed about America’s continued ownership of the Panama Canal: “The world moves, and ideas that were good once are not always good.”

1960s and ‘70s: Presidents Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Gerald Ford each looked for ways out of Panama, yet none were willing to risk the political capital necessary to make it happen. The American trade unions that represented highly-paid U.S. workers in the Zone and key Republicans in Congress were formidable opponents.

1977: President Jimmy Carter was the one to finally wade in and strike a deal that garnered enough Senate support to turn over the Canal and all of its infrastructure to Panama by the end of 1999. One aspect of the agreement, however, remains in place today with no expiration date. The Treaty Concerning the Permanent Neutrality and Operation of the Panama Canal assures the permanent neutrality of the Canal with fair access for all nations and nondiscriminatory tolls. Only Panama may operate the Canal or maintain military installations in Panamanian territory. The U.S. reserves the right to exert military force in defense of the Canal against any threat to its neutrality. This seems to be where President Trump is focusing his argument that Panama might have violated the spirit of The Treaty.

Panama Takes Over and China Moves In

The transfer of the Canal to Panama paralleled the integration of China into the world’s economy. Since the official handover in 1999, China’s rise as a global power made the Canal a logical target to increase its influence in the Western Hemisphere. Nevertheless, this was something brand new. As late as 1978, when the Canal treaties were still being negotiated, China was in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, where capitalism was the declared enemy of the people—and more than 90% of the population lived in extreme poverty.

1997: While the Canal’s transition was still unfolding and China was now part of the global capitalist system, a 25-year contract was granted to Hong-Kong based Hutchinson Ports Holdings to manage the ports of Balboa on the Pacific side and Cristobal on the Atlantic entrance. No American firms bid on the contract; and, hardly no one in Washington noticed when Hutchinson was announced as the winner.

1999: When the official ceremony handing over the Canal to Panama took place in December 1999, the U.S. had tired of the Canal. While the U.S. was by far the biggest user of the Canal, it was less and less relevant to the American economy. Tellingly, it fell to Jimmy Carter, who had been out of office for 20 years, to represent the U.S. at the handover ceremony. The stage was now set for a new, Panamanian-run Canal with new international partners, including China.

Profitability, Expansion and China’s Growing Influence

2000-2005: It is not hyperbole to say that Panamanian management of the Canal since 2000 has been nothing short of remarkable. In the years after the Panama takeover, the Canal has broken records in tonnages, income and profitability. Critical to this initial success was the establishment of global operating standards for the Canal. Immediately after taking over, the Panamanians sought to meet the requirements for earning the ISO-9001 designation: the international standard that specifies requirements for a quality management system (QMS). Under the United States, the Canal had never achieved the ISO-9001 standard. The Panamanians understood achieving it would prove to the world that the Canal was operating at full efficiency with the highest levels of quality assuredness. Further, ISO-9001 validation would allow for the Panamanians to expand the Canal’s offerings to a larger market with regular price increases, which would lead to greater tonnage each year and, ultimately, increased revenues.

Reaching the ISO-9001 threshold in 2001 immediately opened up enhanced communication with the Canal’s stakeholders and clients around the world. A “dialogue of equals” now existed with shipping companies, cargo importers and exporters, producers, and the ports that the ships use.

The results spoke for themselves: between 2000 and 2005, when the Canal was completely under Panamanian control, it was able to pass on $1.822 billion to the government to bring improvements to the people of Panama, a figure nearly equal to what was contributed to Panama during the previous 86 years of U.S. management. All of this laid a foundation of trust in the Panamanians’ management of the Canal, which would serve well the cause of any future expansion plans.

At the same time, the Canal Authority launched a detailed, publicly available series of business, engineering, environmental and archeological studies that explored various aspects of what a Canal expansion would look like.

More Panama Canal and supply chain news from Endeavor Business Media:

Navigating Supply Chain Disruptions: Then And Now

Michigan Governor Says Trump Tariffs on Mexico, Canada Could Harm US Auto Sector

Leveraging data to optimize shipping through the Panama Canal while protecting local water supply

2006: The Canal Authority presented to Panamanian citizens the proposal for the expansion of the Canal through the construction of a third set of locks. The people voted 77% in favor of the expansion.

2007: With a blast at Cerro Paraíso on the Pacific side, work began on the expansion of the Canal. A Spanish/Italian consortium was awarded the contract to design and build the new set of locks.

2016: The expansion of the Canal and its operations, allowing for larger vessels to transmit the lock system, were completed. The first container ship to pass through expanded Canal was Chinese-owned: the COCSO PANAMA. The ship entered the locks on June 26, marking the official opening of the expanded canal.

That same year, China acquired the management contract of Margarita Island of the Colon Free Trade Zone on the Atlantic side of the Canal. This deal established the Panama-Colón Container Port (PCCP) as a deep-water port for megaships.

Read Part II of this series: Trump, China and the Panama Canal

2017: The Panamanian government severed ties diplomatic ties with Taiwan and fully recognized China. This opened-up Panama’s eventual entry into China’s “Belt Road Initiative” in 2018, when it became the first Latin American country to sign. In 2021, under the failing Panamanian administration of Laurentino Cortizo--and despite significant domestic and international opposition--the contract with China’s Hutchinson Ports was renewed for another 25 years.

About the Author

Andrew R. Thomas

Bestselling business author & associate professor of marketing and international business

Andrew R. Thomas' most recent book is The Canal of Panama and Globalization: Growth and Challenges in the 21st Century (2022). He is an associate professor of marketing and international business at the University of Akron.

A successful global entrepreneur, Dr. Thomas was a principal in the first firm to ever export motor vehicles from China. He has traveled to and conducted business in 120 countries on all seven continents.