China will soon shake up the U.S. electric-vehicle market with affordable vehicles, access to critical minerals and innovative approaches to production and styling. That was the overarching message at the Chicago Federal Reserve Automotive Insights Symposium in Detroit in late January.

While the 2023 event centered on what the U.S. EV transformation might look like over time, this year, China was a recurring character in almost every panel discussion, from critical minerals to the long-term outlook for EVs.

Here are five takeaways about China from the conference:

1. Chinese EV makers are coming for the U.S. market.

“How do you cut the price of EVs in half?” posited Kristin Dziczek, automotive policy advisor for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. “China’s already done it.”

Dziczek recalled a Chinese auto show in 2018, awash in fever-dream contraptions that would never make it to mass production. Less than a decade later, she said, Chinese automakers are serious about making electric cars that will sell all over the world—and they are manufacturing them.

“These are not the cars with the fish tanks in the armrests and the shag carpet on the dashboard,” she said.

Dziczek shared a slick photograph of the Seagull (pictured above), an EV by Chinese automaker BYD that retails overseas for $11,500.

“This is the car that scares me,” she said. Even with tariffs, BYD can sell the car in the US for less than $15,000. “Real cars, real quality and really low prices.”

Dziczek noted that as China’s population shrinks, its manufacturing focus goes to exports. “Affordability is still a challenge” for U.S.-made EVs. “We don’t have a lot of lightly used cars. People need a car to get to work in this country. These [Chinese EVs] are going to look very attractive.”

Affordability is a big issue, said Michelle Krebs, executive analyst for Cox Automotive. With prices rising faster than wages, “10 percent of people who normally buy new vehicles have dropped out of that market” because they can no longer afford them, she noted.

2. Trading with China is not optional—the U.S. has to do it for EVs.

“Keeping China out would fracture the U.S. from the rest of the world,” said Mary Lovely, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Access to the Chinese market still remains important for American companies.”

Even when the U.S. restricts trade with China, China provides components for suppliers in countries that are U.S. free-trading partners. China also has a foothold in Mexico and Asian countries that the U.S. trades freely with, building ports and providing manufacturing and logistics services at those ports.

“All of our friends in the Indo-Pacific, except Fiji and Japan, are actually deepening their relationship with China,” said Leila Aridi Afas, Toyota North America’s director of global public policy.

Lovely added that requirements for EV credits in the Inflation Reduction Act give automakers too little time for to move away from China in terms of critical minerals. Even critical minerals mined in the U.S. are sent to China for processing. “So far the U.S. government doesn’t have a clear strategy,” she said.

The U.S. needs to prioritize expanding its critical-mineral processing capacity, said Luisa Moreno, president and director of Defense Metal Corp, a rare earths mining project in the Canadian province of British Columbia. By 2030, as EV demand grows, there will be “a tenfold increase in demand for critical minerals,” she said. “The U.S. produces about 16% of rare-earth minerals They have not been able to process them. So they export 40,000 tons to China to refine.”

Moreno noted that even the machines used to make chips for EVs require rare-earth minerals to function. “Put export restrictions on that, and you can’t make the machines.”

3. The U.S. must view China and other trading partners differently.

U.S. definitions of “friendly” and “unfriendly” trading partners are too rigid, said three members of the critical minerals panel.

“Countries that have these resources are not necessarily our friends,” said Aridi Afas. “And like-minded countries, these countries are one election away from not being our friends. … Can we look at it more strategically, that we have something to offer each other?”

Instead of a system of tariffs and bans, said Aridi Afas, trade policies should focus more on carrot than stick—giving emerging economies like Indonesia environmental and human rights standards to meet in order to trade with the U.S. With that approach, “now we’re opening up to these countries,” she said.

Line are blurred between “friendly” and “unfriendly” countries to the point that the labels aren’t useful in trade policy, said Christine McDaniel, senior research fellow at George Mason University. “We’ve been doing business with Saudi Arabia—do they share our values? … Different countries have different cost structures. That doesn’t make them not our friends. Even Mexico, they’re sending their cartels across the border. Is that our friend?”

Bringing countries up to U.S. standards is a better negotiating chip than tariffs, Moreno said.

Safety Concerns, Unsustainable Subsidies for Chinese EVs (Reader Feedback)

I'm the vice president of marketing and business development at Cadillac Products Automotive Company (CPAC). We are a small, family-owned and -operated company with three plants in Michigan and one in Texas. We are a Tier I supplier to the Detroit 3 automakers and the heavy-duty-truck OEMs. Our main product lines are in the areas of acoustic, thermal and moisture management.

I was present at the Federal Reserve Bank gathering in mid-January and listened to the presentations and as you accurately describe there was a focus on China.

I enjoyed your article and the highlights from the panels. There is always something about all the discussions about China that rarely ever is mentioned. That would be the significant role that the Chinese government has played in mandating electrification and how they have fiscally supported it. China has an advantage not only through their natural resources for raw earth minerals, but the size of the marketplace provides a built-in market. China can force its people to buy EV’s through mandates/regulations. This provides the market to allow the OEMs to establish themselves, which provides the capital to focus on establishing a presence globally. In the West, the various governments can mandate through regulations on the OEMs. They cannot force the people to buy them. This is what we are experiencing today. General Motors is refocusing on plug-in hybrids as perhaps a better solution until some more affordable options are in place.

Enough of my opinions. What does not get much exposure in China is how much the government has supported the establishment and growth of the EV industry. At some point, the investment will diminish/cease. Then will BYD remain in a position to sell EV’s at an $11,500 and make a profit? Let’s not forget the Seagull is not available in the USA for various reasons. Also, I have not been able to find a NHTSA Crash Test result for the Seagull. Nobody asks who is assembling these vehicles in terms of forced or child labor. However, it is appropriate to acknowledge the potential threat that these vehicles represent.

Thanks for your reporting; I enjoyed it.

— Scott Paradise

4. Chinese automakers are looking to Tesla for production innovation—to their advantage.

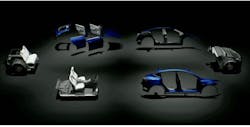

Chinese EV startups Xpeng and Zeekr (a Geely subsidiary) are using Tesla’s gigacasting production approach to cut weight, cost and manufacturing footprint by greatly reducing the number of parts that make up a car. BYD and others are also borrowing from Tesla’s modular vechile design principles to make similar reductions and speed up the production process.

Gigacasting is the process of using massive high-pressure machines to cast much larger, more complex pieces of an EV body in single pieces, eliminating many steps in stamping and welding and reducing the manufacturing footprint.

Mathew Vachaparampil, CEO of engineering consulting firm Caresoft Global, gave several examples of how Tesla-style modular architecture is reducing costs. Caresoft does 35-40 vehicle teardowns each year for research purposes. Some findings:

Unlike legacy vehicles, the body-in-white of the Tesla Model Y built in Austin, Texas, has no discrete floor; the floor of the vehicle is the battery. The body-in-white weighs 333 kilos, versus legacy automakers’ 458 kilos.

With gigacasting in the back and front of the vehicle and battery-as-floor, the Tesla gets 14% better range, 10% mass reduction and has 317 fewer parts than a similar legacy vehicle.

From the Tesla Model 3 to the Model Y Austin, Tesla has reduced total parts by 63%, to 141 parts.

Tesla’s design for its next-generation vehicles divides the body in white into two parts that are assembled in parallel rather than a serial assembly line; builds up the interior from the battery floor rather than after the vehicle is assembled; and paints as the final step--saving on labor and painting costs.

Chinese startups have resources for gigacasting, as they are starting from scratch on their manufacturing footprint, not having invested billions of dollars in stamping and traditional tooling equipment. However, legacy automakers including Volvo (a Chinese-owned company), Toyota and Volkswagen have also been looking into the possibilities of gigacasting. In November, General Motors purchased a Tesla gigacasting partner, Tooling & Equipment International (TEI).

Of the legacy automakers, Toyota is probably furthest along at adopting Tesla’s methods. “There’s a lot of learning, back and forth, but I was really struck when the news came out that Toyota, not on a low-volume or low-cost car by on the Lexus, is going to look at moving to the Tesla production system," said Dziczek. "You know, the [Toyota Production System] is a holistic system. It’s not just production and design, it’s about management, it’s about quality. It’s about a billion other things. And to me, this combination of Tesla’s design and speed with Toyota quality and efficiency could be an absolute juggernaut. And then you have the Chinese coming very fast on their heels, adopting everything, moving fast and changing all the time.”

5. China can comply with USMCA and avoid tariffs.

Under the Rules of Origin of the United States-Mexico Canada Agreement, 75% of a vehicle's content must be sourced in North America, or that vehicle will be subject to foreign-made tariffs. As long as they are compliant with USMCA rules, Chinese automakers can bypass tariffs. Some Chinese EV makers already have a U.S. manufacturing footprint in one form or another. BYD has a U.S. factory making battery-electric buses. And Geely, manufacturing EVs under the Zeekr brand, owns Volvo, which has a manufacturing plant in South Carolina.

But can a $15,000 EV made in China actually gain traction in the U.S.? "I don't know that what flies in China is going to fly in the U.S.," said Colin Langan, automotive and mobility analyst, Wells Fargo. "So maybe the slow path isn't necessarily wrong. I think there's potential [with gigacasting]. I think the traditional guys should be looking at it, but I don't think it's a slam dunk."

About the Author

Laura Putre

Senior Editor, IndustryWeek

As senior editor, Laura Putre works with IndustryWeek's editorial contributors and reports on leadership and the automotive industry as they relate to manufacturing. She joined IndustryWeek in 2015 as a staff writer covering workforce issues.

Prior to IndustryWeek, Laura reported on the healthcare industry and covered local news. She was the editor of the Chicago Journal and a staff writer for Cleveland Scene. Her national bylines include The Guardian, Slate, Pacific-Standard and The Root.

Laura was a National Press Foundation fellow in 2022.

Got a story idea? Reach out to Laura at [email protected]