Manufacturing’s Back Is to the Wall on the Skilled Labor Shortage

Multinational corporations are today faced with a changing world economy. Cracks have formed in their outsourcing model, and they are being forced to re-examine their supply chains. The total cost of manufacturing overseas has risen because of:

- Increased foreign labor costs

- Increased transportation costs

- Intellectual property theft

- Long lead times

- Problems with joint partnerships

- The loss of technologies through forced technology transfer agreements

- Trump’s tariffs

- The distance from consumer markets

- Product quality and customer satisfaction problems

- Shortages of critical materials to manufacture semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, electric batteries, etc.

These problems have been exacerbated by Russia’s war in the Ukraine and China’s zero-COVID policy, which led to lockdowns in many cities and a resurgence of port congestion. The problems have made Chinese supply chains an expensive and risky proposition. American corporations including HP, Stanley Black & Decker, Dell, Sony, Caterpillar, GE, Intel, Under Armor and others have moved production out of China, sometimes to the U.S.

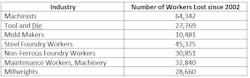

Surveys show that reshoring production from China is now popular with most American citizens. According to the Reshoring Initiative, around 224,000 manufacturing jobs were reshored in 2021.While champions of reshoring are enthusiastic about a potential American manufacturing renaissance, the U.S. simply doesn't have the skilled workers necessary to handle reshored production. The shortage of skilled workers in manufacturing has been a known problem for 30 years, but little was done to avoid the current shortage. There are two causes. First, manufacturing has been losing skilled workers for decades. The Department of Labor databases shows the following losses in skilled employees from 2002 to 2021.

The last two maintenance categories are critical because they must keep all of the automation running in these highly automated production lines. But not enough new maintenance workers are being trained to fill the gap of retiring workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says there are 152,300 openings for general maintenance and repair workers projected each year. In addition, a 2018 survey by Deloitte/Manufacturing Institute projects 2.69 million more manufacturing workers will retire by 2030

The American Welding Society predicts a deficit of 400,000 skilled welders by 2024. A 2018 survey by Deloitte/Manufacturing Institute projects 2.69 million manufacturing workers will retire by 2030. Skilled workers in the manufacturing sector are retiring much faster than they can be replaced

Second, there is also an urgent need for entry-level workers, but recruiting them is a big problem. Manufacturing must compete with employers such as Amazon and UPS that offer higher entry wages and bonuses. The latest data from the Labor Department’s JOLT database shows that there were 860,000 unfilled manufacturing jobs in March 2022. Entry-level workers can get $22 per hour at Amazon and $15 per hour at fast-food restaurants. This scenario is complicated by the fact that in February 2022, manufacturing quits hit 337,000 (2.7% of the manufacturing workforce) and many young workers go from job to job collecting signing bonuses.

In addition to the problem of reshoring production, we also need skilled workers for the federal infrastructure program. The government announced in May 2022 that there were 4,300 projects underway, with $110 billion in federal funding. According to the Biden administration, the infrastructure program will require 556,000 new workers, and many of those jobs are in manufacturing. The skilled worker shortage problem is now upon us, and corporations are faced with training and recruiting thousands of new employees.

How Did We Get into This Jam?

The trend against vocational training began in the early 1960s, when the federal government began to push college education over vocational and technical training. Schools began to close down shop classes and convert them to computer classes to support the “college first” agenda. Parents also bought into the college degree as the highest priority for their children—and suddenly, working with your hands became “uncool.” The priority is still college first, and the federal government spends far more on college prep than it does on vocational training. As a result, several generations have missed out on the opportunity to gain the skills to get a good-paying job without a college degree (or the loans to go with it).

Then, in the 1970s, American multinational corporations began outsourcing production and jobs. For a long time, they were able to operate without investing in technical training by automating, buying foreign services and poaching skilled workers from their suppliers. But now those short-term strategies no longer work, and these corporations are faced with a massive worker shortage problem.

The Problem Is Twofold

Entry-level workers: Even though most manufacturers have raised their minimum wage to at least $15 per hour, they are not being inundated with applications. The big question is, “Why would a worker commit to an industry that laid-off millions of manufacturing workers and was primarily responsible for devastating families and economies in towns like Dayton, Ohio; Danville, Virginia; Johnstown, Pennsylvania; and Newton, Iowa.

Skilled workers: The bigger problem is that to reshore production, corporations need workers with the same skills as the workers who are currently retiring. For the most part, these are highly skilled people who have gained their skills over 25 to 30 years. It isn’t a matter of taking a few online or community college courses. It is going to take a serious investment in advanced “hands-on” training to create the machinists, tool-and-die makers, assemblers, welders and maintenance people they need today.

The National Association of Manufacturers and their Manufacturing Institute have been surveying their members on the skilled worker shortage for 30 years. They have measured the loss of skilled workers year to year, but there is no evidence their membership anticipated the current crisis of skilled and entry level workers by making the necessary investment in the training programs to replace retiring workers.

In fact, a January 2020 training survey by the Manufacturing Institute shows that the average number of hours of training, per employee, among their members is only 27.7 hours per year—and for new employees it was 42.9 hours per year. The study says that “75% of industrial organizations identified reskilling the workforce as important or very important for their success over the next year, but only 10% said they were very ready to address this trend.”

My assumption is that if a good percentage of these jobs are highly skilled, then we will need advanced or long-term training like apprenticeship training. The problem is, manufacturers do not want to invest in training that takes thousands of hours to complete. I have been following the Office of Apprenticeship training’s website since 2001, and the total annual number of registered apprentices in manufacturing has not increased at all in the manufacturing sector since that time. Meanwhile, apprenticeships in other sectors like construction are growing.

The Consequences Are Here

Despite all of the publicity, high school workshops and Manufacturing Day ceremonies, I don’t think the public’s view of manufacturing is going to change until the multinational corporations can address the issues of job security, training and wages. The days when manufacturers could put an ad in the paper to find either a skilled or entry-level manufacturing worker for the most part are over. They are fishing in a shallow lake that has been fished out. If manufacturing wants more skilled workers, they're going to have to create them from scratch. They need to invest in the advanced training necessary to create the skilled workers they need now and in the future.

Here are some specific recommendations.:

- To change the view of manufacturing as an unstable industry is going to require corporations to publicly address the problem of outsourcing and job security.

- Manufacturers also need to publicly commit to long-term job training and paid internships to replace the highly skilled workers leaving the industry.

- The industry will also have to match the starting wages of Amazon and FedEx to get their fair share of entry workers

It appears manufacturing has few options left. If companies want to reshore production to the U.S. or bid on the upcoming infrastructure projects, they are going to have to bite the training bullet and create the skilled workers they need.

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream, How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net