Once an opera singer, Mike Rowe began his television career by selling tchotchkes on QVC. He parlayed that into a successful career hosting industrial jobs-focused shows including Dirty Jobs and Somebody’s Gotta Do It, as well as stints as a pitchman for Ford and Caterpillar. Many wish the outspoken advocate for hard working Americans would run for president someday, but Rowe’s acumen for honesty, logic and reason preclude a career in politics. Instead, he used his various platforms and smooth, baritone voice to eloquently echo the message industries such as manufacturing have wanted, but couldn’t quite articulate for decades: We need skilled somebodies to do the dirty jobs.

And as great a voice that he has, and is, Rowe knows talk is much less valuable than sweat equity, so for the last decade, through mikeroweWORKs, the Baltimore native has amassed millions to award scholarships to those who exude the work ethic and determination America needs right now and are interested in learning a skill or mastering a trade. Oftentimes, it’ll lead to a much happier and profitable future than owing your soul to the new company store, the U.S. higher education system.

For the 3.6 million teenagers graduating from high school this spring, Rowe’s message about following opportunity, not passion, seeking challenges and not safe spaces, should come as a warning and relief. Like amassing $100,000 in student loans for a four-year degree, trying to explain this message better than Rowe is folly. So we went to the man himself to explain what it all means and how we can tackle the skills gap that will only widen with every graduating class.

John Hitch: What do you think about the state of the manufacturing industry and the future of its workforce?

Mike Rowe: Honestly I don't look at manufacturing in that isolated the way. To be honest, I'm not even sure what it means anymore. I know it means making things. But to me the notion of learning a skill and mastering a trade is still as for sale as it's ever been. What does that mean in the manufacturing sector, vis-à-vis automation, new efficiencies, and things like that? I know that that's a big headline, but I don't really know that I'm qualified to talk specifically about the future of manufacturing.

I'm comfortable saying if you try and separate blue collar from white collar, and if you try and separate the skilled trades from manufacturing in general, then I feel like you're splitting the baby and you're talking about heads, but not tails. What's really on the table, I think, is a much larger dysfunctional relationship with work in general.

So the business of mastering a skill and the idea that a skill can lead to prosperity, that's the thing that I feel like has been maligned. And we look for examples in my foundation to prove that that path still exists. But does it always land in the classic manufacturing job? I'm not sure, because that industry is changing so fast I can't keep up with it. But I still know in a very general way that the impediments to recruiting in manufacturing are higher than they've ever been, and it just doesn't make sense given the openings that are available. So it has to be being caused by something else, something social, something a societal.

JH: I've been doing a lot of stories in the last couple of years just on STEM, coming across studies such as one that says 52% of teenagers aren't interested in any job in manufacturing…

MR: I think acronyms are tricky. They're clever and then they get socialized and now everybody is like, “Oh good, you know science, technology, engineering and math.” But I went on a rant a few years ago that it should be STEMS. There should be another “S” at the end that should be for skill, because if you don't include skill in the acronym, then you just marginalized its importance by making its absence so conspicuous.

And then I ran into these guys who were doing a thing called the STEAM Carnival. There’s STEM again, but they were all pissed off because the “A” wasn't in there for the Arts. And I sympathize, because if you really look at the way shop class was arbitraged out of high schools, it started by taking the art out of the vocational arts and then making it just votech and then just making it shop. And then you walk out behind the barn and shoot it in the ear.

And there simply is no better way to show what's important than by removing it from his sight. I just feel like a lot of these conversations about the future of manufacturing, the future of the skilled trades and the widening skills gap, etc., it has to start with the fact that these things can't be mysteries. These things are the logical results of completely removing an entire discipline of vocations from the sight of parents and kids.

JH: On your Facebook page last month, a woman who didn't like one of your recent diatribes on the skills gap and hard jobs fired back at you that not everyone wants to have a hard job. Is there a misconception where these skilled jobs have to be dirty and dangerous?

MR: The problem isn't that so much has changed in that world; the problem in my view is that higher ed needed a PR campaign in the ’50s and ’60s. We actually needed more people to enthusiastically matriculate through universities. Society really could benefit from more liberal arts, classical thought and more people with a broad-based understanding of stuff. And so the push for college in my view was legitimate. Unfortunately, the push for college came at the expense of other forms of education. And this is just a classic trap in most forms of advocacy and PR. You promote one thing not to the betterment of itself, but at the expense of the other.

So the proposition became: “if you don't go to a four-year school, you're going to wind up over here in this shit hole. But if you wind up over there, then the kind of job you're going to get is going to make you want to kill yourself."

So the whole transaction became fraught with false consequences. That's how we promote it.

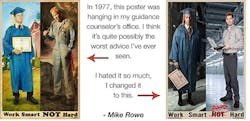

I still have a poster that was in my guidance counselor’s office that was really one of the first attempts to broadly promote college with a platitude, and the platitude was “Work smart, not hard.” And that's really where a lot of people just assume it's a logical thing with regard to heightened efficiency. And of course it is. But that caption appeared on a photo of a kid holding a diploma next to a skilled worker holding a wrench and looking like he just won a vocational consolation prize.

When you start telling kids that if you don't work smart, you'll have no choice but to work hard, you're giving them this "Let's Make a Deal” choice, where behind the curtain is nothing but a box of Borax or a brand new, shiny Corvette. It's not fair, it's not right, it's not sensible. But that basic notion has infected and informed a big chunk of our culture, and consequently you've got well over $1 trillion in student loans on the books and you've got over 6 million jobs that are currently open, many in manufacturing, many in the skilled trades — and few of which require a four-year degree. So that's your disconnect in a nutshell.

Today we have this notion that if you're unhappy in your work it's because your work is making you unhappy. And that's what I mean when I talk about a general war on work. It's a bit hyperbolic but as Dirty Jobs proved every week, I can show you people doing difficult and dangerous things that are clearly and demonstrably dirty. These are not the jobs your parents hope and pray you get. And yet the people are happy they're having fun they're engaged and they know that what they're doing has meaning. So that was a big lesson in that show.

JH: Watching YouTube videos of your stint at QVC, where it clearly wasn’t what you wanted to do, but made it look fun, is this current advice analogous to your own past experience?

QVC was not the job I wanted. It was not the job I dreamed of. It was not the job I’d considered. I was fired from it three times in three years. However, I had an absolute scream working at QVC, and for as much fun as I make of them these days, to be honest, it was the most valuable training I ever got. It was it was the ultimate apprenticeship for me from my industry.

And at the time, I just took the job because I needed some money. I had no aspirations to sell stuff in the middle of the night to a bunch of narcoleptic codependents. It was the last thing in the world on my mind, but I could see that it was a business and I respected the skill that it took to sit on live television for three hours at a time and not go up in flames.

So I appreciated the challenge of doing that. I approached it very differently than my counterparts -- and to the horror of my many bosses. But the fans loved it. So if I were writing a book called Lessons from the Dirt, I would start by telling you what I learned at QVC. And I would make it very analogous to the importance of getting a tool box for the basic industry you want to work in. And that's what I think more people could benefit from doing.

I don't think many people could benefit from selling the Core Negative Ion Generator at 3:00 a.m. like I did. However, I think a lot of people could benefit from opening a toolbox full of more traditional tools and going to a job site and spending six months, nine months, 18 months learning how to weld, learning how to hang sheet rock, learning how to do the basics, learning how to build something. Because once you have that skill that goes with you and those skills you know those aren't going to vanish.

JH: Do you think there’s a lack of work ethic with the younger workforce, and that’s why they are turning down solid assembly jobs for easier work for less pay?

MR: Millennials are an easy target. And I hate to generalize, so I don't like to just say the obvious thing and take the obvious shot, but our scholarship program through mikeroweWORKS is called a Work Ethic Scholarship Program. And to apply, you need to jump through all kinds of hoops that annoy all kinds of people who don't want to have to make a video. They don't want to have to write an essay.

They ask, “Why should I have to submit references? Why do I have to make a case for myself?”

I make them sign something called a sweat pledge. It's a 12-point promise that essentially affirms a belief in personal responsibility personal accountability. It's full of things that a lot of people bristle at today. So they say, “Well I'm not sure I want to sign this.” And I say, “That's cool. I'm not sure this particular pile of free money is for you.”

JH: Is there any indicators or personality traits that you've picked up on visiting the hundreds of factories and sites where you can look at a person and say, “These are the two worth three definitive factors to help someone be successful in the trades”?

MR: That's really a terrific question, and my honest answer is “No.” The people who I know that are successful in the trades are no different than the people I know who are successful in my industry. My working supposition is that anybody can be a tradesman.

I love that word and I think it should be way more broadly defined. If tradesmen can only be blue collar workers, and if blue collar is fundamentally pejorative, then tradesmen are fundamentally subordinate. That's a tautological trap. I think that anybody can approach their work like a tradesman.

My grandfather was a tradesman. He could build fix repair anything. He only went to the seventh grade and he was a master plumber, steam fitter, pipefitter, architect and welder— and he could work. He had ultimate job security even though he wasn't employed full-time.

I guess what I'm saying is that being a tradesman is a state of mind and whether you're welding or selling tchotchkes in the middle of the night on QVC. You chose a trade and now it's incumbent upon you to get a toolbox that has tools in it that you've mastered. And I'd say the same thing to a lawyer or an accountant or a crab fisherman or whatever. If we think of the business of learning a trade or becoming a trade person as a mental state instead of a vocational distinction, then we’re probably on the right track.

JH: You have spoken about the problem of passion without the skill to back it, such as all the train wrecks on American Idol. If you’re a parent, how do you handle that tactfully, telling your kid who wants to be a doctor they are better off becoming an electrician?

MR: Well the first thing you do is you as you acknowledge the accepted progression and the accepted progression is, “think about what you want to do, identify that thing and act the plan.”

You go to college, borrow money, interview, move if need be. And then you will eventually find yourself in the position that you have said will make you happy. That's basically how it works. And that's what that whole “follow your passion” thing was. I didn't say, “Don't be passionate.” I said “Don't follow your passion,” because your passion can exist separate and apart from your ability. And just because you're passionate about becoming an American Idol doesn't mean you're going to win. It doesn't even mean you're going to get a shot. So I wouldn't tiptoe around that. That's a that's a big, giant, basic truth And I don't think the whole notion of everybody getting a trophy or the ascension of safe spaces has done anybody any good at all.

I think it's just fostered a completely unrealistic view of the world. So I wouldn't tiptoe around the truth of that but I would also suggest there's another way to go. And the other way is if you're going to follow something, follow opportunity. Take your passion with you. There's no excuse for doing something you're not passionate about.

You only get to one life. If you're going to be a welder, be passionate about it. But don't tell me you can't be passionate about it because you don't like it. That's a choice. It's a long way of saying “eat your peas.” And I don't want to sound like a grumpy old guy on the on the porch yelling at kids to get off the lawn. I really don't. But that's what I can leave you with. That's the big lesson of Dirty Jobs. When you find somebody who's in a septic tank working their ass off laughing, sweating and prospering all as a result, you can't deny that that person is passionate. That person is engaged and that person is prospering. But they didn't get there because somebody said, “Hey look, you're 17. What do you want to do?”

No, they look around and they say, “You know what. Nobody's cleaning septic tanks. That looks like an opportunity."

They pursue it then they figure out how to get really good at it. Then they figure out how to love it.

About the Author

John Hitch

Senior Editor

John Hitch writes about the latest manufacturing trends and emerging technologies, including but not limited to: Robotics, the Industrial Internet of Things, 3D Printing, and Artificial Intelligence. He is a veteran of the United States Navy and former magazine freelancer based in Cleveland, Ohio.

Questions or comments may be directed to: [email protected]