Understanding the Demand/Capacity Curve, Part 2: Why is It So Difficult to Work with Intercompany Suppliers?

Editor's Note: This is a companion piece to “Understanding the Demand/Capacity Curve.”

If you were to ask operations leaders who their most difficult suppliers are, the answer would most likely be plants from other divisions within the same company. (We will refer to these plants as intercompany suppliers.) Why is it so difficult to deal with internal plants that should have the best interests of the parent company in mind--especially if the leaders own company stock or are part owners? The demand/capacity curve may provide some insight and put you on the path to making such supplier arrangements work more smoothly.

“I have some news from the corporate office,” says the business leader of the ABC division to her leadership team. “Apparently, our Dallas plant in the XYZ division has extra capacity and has the capability to produce some parts we currently buy. Our CEO was convinced by their leadership team to put out an edict that we start buying our parts from this internal plant in order to utilize some of this extra capacity.”

“Dang it!” exclaims the leader of operations as he hits the conference table with his fist. “I know which parts they are referring to, and our entire operation is dependent on those parts. If they have any hiccups in quality or delivery, our entire plant will be impacted.”

“We currently have a strong external supplier who we partnered with several years ago,” adds the director of procurement. “Their performance has been outstanding over this time. We have been able to cut our inventory level of this part dramatically since we don’t have to worry about their quality and ability to deliver on schedule.”

“Hey, I don’t like it either,” says the business leader. “I don’t even want to think about how our future business performance will be in the hands of another division. However, I don’t think we have much choice in the matter. So, let’s try and make this work.”

“I assume we will use the corporate standard of cost plus 10%,” says the plant controller. “Hopefully, the internal price will be similar to what we currently pay the external supplier. Otherwise, we will need to readjust all of our projections for the year.”

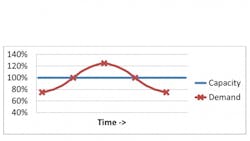

In this example, the demand/capacity curve for the intercompany supplier plant in Dallas would look something like Figure 2. We will assume that even with the added needs from the intercompany customer, the total demand is below the capacity line.

The business leaders in the XYZ division that is supplying the parts will have a strong desire to sell their capacity to their own external customers, especially if they can make more than 10% profit. The sales team at the XYZ division, who are probably on commission, will continue to push product. So, demand at the intercompany supplier plant in Dallas will eventually start to increase toward the capacity line (Figure 3).

This increase in external demand plus the need to meet intercompany customer needs puts the Dallas plant in a mode where the only way it can keep up is to work mandatory overtime.

“They claim that the only way to meet our needs is to work Saturdays and Sundays,” says the director of procurement. “The quantity of parts we are ordering has not changed, but they are struggling to keep up.”

“What happened to all of that extra capacity they had?” says the leader of operations.

“I will call the V.P. over at the XYZ division and see what is going on,” says the business leader. “I have a bad feeling that this is not going to end well.”

Meanwhile, the sales team at the XYZ division continues to push product to their external customers, driving total demand well above capacity. At this point, the Dallas plant production begins to fall apart. There is no way to meet the demands of all of the external customers, which means that the internal customer's needs are almost completely ignored. Expediting becomes a way of life as “priority customers” get their needs met first. The intercompany supplier in Dallas is now at the top of the demand/capacity curve (Figure 4).

“Yeah, I have several operators dedicated to sorting their parts just to keep the plant running,” says the leader of operations. “At this rate, I expect we will be shut down by this time tomorrow.”

“Maybe we should consider going back to our original external supplier,” says the business leader. “I know the CEO will give me a lot of grief, but at this point, I don’t see that we have much choice.”

Original Supplier 'Ticked Off'

“The original supplier is still ticked off at us for pulling the business in the first place,” says the director of procurement. “Also, since they have a great reputation, they were able to get some new customers and fill most of their capacity pretty quickly after we left. I floated the idea of them making parts for us again, and it looks like the price will go up substantially.”

“I don’t see that we have any other options in the short term,” says the leader of operations. “We can’t afford to keep running this way. It is clear to me that we need to stock more parts to keep this from happening again. I want to increase the amount of inventory on the shelves substantially to provide us some protection!”

“I am not sure that is such a good idea,” says the director of procurement. “That extra inventory is going to tie up a lot of cash and consume most of our warehouse. Plus, I have heard a rumor that engineering is about to make a product change that could make this part obsolete.”

“I guess that is a chance we will have to take,” says the business leader. “We can’t afford to shut the plant down again or we will have no chance at all of hitting our goals for the year.”

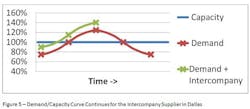

So, the director of procurement scrambles to find other sources for this part and ends their reliance on the intercompany supplier. Meanwhile, the performance of the Dallas plant in the XYZ division continues to worsen, which results in a loss of trust from their external customers as well, and demand eventually drops back below the capacity line (Figure 5).

“You will not believe who just sent me a text message,” says the business leader with a sigh. “Apparently, the plant in Dallas has extra capacity again, and the XYZ division wants to know when they can start sending us parts. I told them what they can do with their parts, but that just made them angry. I would not be surprised if they go to the CEO again for another edict.”

“Wow, you sure know how to ruin my day,” says the leader of operations. “If we don’t do something different this time, we know what will happen. I guess we better keep that extra inventory after all.”

Conclusion

When the demand curve drops below the capacity line, even for a short time, there is pressure to fill that extra capacity quickly with intercompany business. However, the real total cost to the company may make this a bad business decision in the long term. The intercompany supplier may be tempted to service its own customers before meeting the needs of the intercompany customer, especially if demand goes up. This could result in an increase of inventory, poor delivery and quality performance, and the potential to shut down plants due to a lack of parts. Also, a barrier will form between business units as trust becomes an issue. This will result in the inability to share best practices and resources internally, and the corporation becomes nothing more than a holding company.

Is it possible to make intercompany suppler arrangements work? Yes, but it requires a strong commitment from everyone involved. The first step would be to have the supplying plant identify its bottleneck operations and calculate its capacity. This of course assumes that its processes are stable and predictable. If the business leaders forecast that future demand will stay below the capacity line, then there may be an opportunity to use this extra capacity internally.

It may also make sense to use the extra capacity of non-bottleneck operations for intercompany use. However, remember that bottlenecks can move, especially if there are changes in the processes. In either case, if parts are supplied to internal plants, the leaders of both divisions and the top executives need to have an agreement on delivery and quality metrics and be just as accountable as they would to an external customer.

The payback for making this work could be substantial as both divisions benefit and trust is restored, allowing additional resources and best practices to be shared in the future.

John Dyer is president of the JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 28 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. Dyer can be reached at (704) 658-0049 and [email protected]. You can view his LinkedIn profile here.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.