US Automotive Industry: A Dominant Link in North American Supply Chains

Perhaps no sector is more symbolic of American manufacturing prowess than the automotive sector. Ever since Henry Ford pioneered the assembly-line model of manufacturing, the sector has been synonymous with advanced manufacturing, whether it be improvements in processes to improve quality and reduce production costs, or the use of robots and other sophisticated machines to design and assemble cutting-edge vehicles.

But worries about the competitiveness of U.S. automotive manufacturing have mounted in recent years. The big 3 (GM, Ford and Chrysler) accounted for just 45% of U.S. car sales in 2014, down from nearly 70% in 2000, and the bailout and subsequent shrinkage of General Motors during the Great Recession left the impression that this trend might continue. An increasing trade deficit and the rise of Mexico as a regional automotive hub only reinforced these worries.

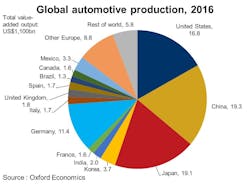

From a global production perspective, however, the notion that U.S. automotive sector is in terminal decline is belied by the facts. In fact, that share has been remarkably stable since 1980—the long-term average is about 20%, and it has rarely deviated from that by more than a few percentage points. Currently, the U.S. global production share stands at 17%, which is an improvement from the 14% reached at depths of the Great Recession.

In sharp contrast, other historical automotive powerhouses have seen their share of manufacturing slip markedly over the past 25 years. Japan’s share has dropped by 15 percentage points and Germany’s seven percentage points.

Much of this is due to regional competition (South Korea and China in the case of Japan and Eastern Europe in the case of Germany), by which manufacturers relocate to the lowest-cost location within a regional market. On this count, it is significant that Mexico—which has had access to the US market for more than 20 years via NAFTA—has seen its share of global production increase by just one percentage point over that period.

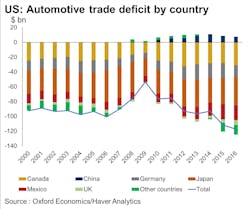

Regarding the broader trade situation, it is true that the automotive sector is chronically in deficit to the tune of about $100 billion per year. There was a dip during the financial crisis, but since then the trade deficit has returned to, and even begun to exceed, historical levels.

But a look at the country distribution reveals some surprises. From 2010 onwards there has been a surplus to China, which in 2016 shaved a little more than 5% of the total trade deficit. In a case of offshoring in reverse, Volvo, now owned by Chinese automaker Geely, has recently begun construction of a factory in South Carolina to produce a sedan that will be exported to China beginning in 2018.

Another observation that may surprise readers is that Mexico is responsible for a relatively small amount of the trade deficit, far smaller than for Japan or Canada. In 2016, the trade deficit was $20 billion (about 17% of the total), just slightly above its long-term average of 14%.

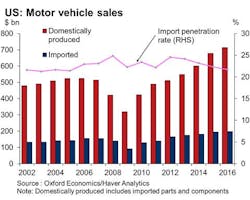

But one of the main reasons why imports (and by extension the trade deficit) have been rising in recent years is that U.S. automotive demand has soared since the Great Recession (more than doubling in value terms), and both domestic and foreign producers have benefited.

The import penetration rate in value terms has actually declined slightly in the past four years, returning to the 22% level that was typical in the early 2000s. This implies that domestic producers have taken a small amount of market share back from imports in a fast-growing market, rather than being an indication of a loss of domestic competitiveness.

The fact that U.S. production has been relatively stable even as the Big 3 lose significant market share is a testament to the attractiveness of the U.S. as a regional manufacturing hub for foreign manufacturers.

According to the most recent data available, foreign-owned firms account for 36% of U.S. automotive output in 2014, up from 23% just seven years prior. Honda opened its twelfth U.S. factory in Ohio last year, and now exports more cars from the U.S. than it imports from abroad.

Other Japanese, South Korean and German manufacturers, have significantly boosted investment in southern states, which offer highly skilled nonunionized labor forces and relatively low wages. While additional investment may be encouraged by the threat of protectionist measures by President Trump, the economic case for investment is sufficiently compelling on its own—along with the nearly 400,000 jobs that go along with it.

A final point is that direct indicators of U.S. automotive competitiveness strongly corroborate the evidence from sectoral production, trade and investment patterns discussed above.

Labor productivity in automotive manufacturing has increased by an average of 4.2% per year since 2000, second-fastest among major manufacturing sectors and a full percentage point above that for overall manufacturing—though a stall in 2016 warrants some concern. Embedded in this performance are significant investments in the latest capital equipment and automation, a myriad of product and process innovations, and a cost-effective skilled labor force that delivers excellent value for money.

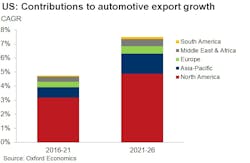

So even as Mexico continues to develop as a complementary manufacturing hub, the U.S. automotive sector, far from being down and out, is and will remain a dominant force in North American automotive supply chains—not only serving its own large domestic market, but export destinations elsewhere in North America and beyond.

Jeremy Leonard is Director of Industry Services at Oxford Economics, and Max Anderson is an Industry Economist at Oxford Economics.