Of Fat and Fault Tolerance: A Biological Paradigm for Supply Chain Management

I’ve read with great interest lately a number of studies that have been published over the last few years exploring the relationship between weight and both mortality rates and life expectancy. Perhaps one of the most interesting of these studies is, “BMI and Mortality: Results from a National Longitudinal Study of Canadian Adults,” jointlyauthored by a number of scientists at Portland State University and health insurance provider Kaiser. The study concluded, among other things, that mortality rates in a population consisting of persons 60+ years of age were the lowest for those persons that were slightly to moderately overweight. The study further concluded that being either underweight, or being considerably overweight, significantly increased mortality rates. Other studies in the U.S. and Australia have shown remarkably similar results. All things being equal, it would seem that it is better to be a little bit too fat than a little bit too skinny.

Not all Fat is Created Equal

The specific research I’m citing for this article, however, makes no attempt to explain either the correlation observed between a few extra pounds and a slightly longer life, or why being a bit thin may shorten one’s life. So I discussed this research with a few medical professionals and it turns out that the results of these studies were not at all surprising to them. It seems that a wide range of different diseases and maladies cause weight loss and other symptomatic manifestations that reduces a person’s strength and lowers their immunities, and therefore reduces their ability to fight off the disease. People that have a bit of extra energy reserves in the form of stored fat may be better equipped to fight these diseases and/or have more ability to survive aggressive treatment. People who are quite lean inherently have fewer reserves to sustain them and buffer them against the deleterious effects of disease.

According to noted physician and weight expert Dr. Albert Simeons, the human body contains three basic types or categories of fat:

- Structural fat – this is normal fat under your skin, around certain organs, and even on the bottom of your feet. This fat is vital and necessary for a normal healthy life.

- Reserve fat – human bodies have the ability and natural tendency to store excess energy in the form of fat that can later be converted back into energy to sustain bodily functions for short periods of time (days or weeks) when food is unavailable or scare.

- Abnormal fat – dramatic excesses of fat caused by prolonged, consistent overeating or metabolic anomalies.

It seems to me that this biological explanation of the different categories of fat, and the scientific observations about fat levels, resilience and fault tolerance, can help inform our views of today’s supply chains. Perhaps a little bit (or in some cases a little bit more) structural fat in the supply chain could both enhance economic performance and improve fault tolerance.

It was just about 18 months ago that the high tech world was sent reeling from a series of natural disasters that wreaked havoc on the supply chains of a number of the world’s most notable tech names. The relentless drive towards ever leaner and ever more “efficient” supply chains had left many companies with supply chains that provided very low total costs – but that were lean to the point of fragility and high susceptibility to shocks. Many of the basic practices that led to the lowest total supply cost also provided the lowest total supply chain resiliency. A super lean supply chain can be an outright disaster, from a disaster recovery perspective. Concentrating production in plants with super-scale economies can certainly provide a lower product cost (in most cases) than producing in numerous, sub-scale factories – unless of course something happens to that super-scale plant. Clustering most of your key suppliers in close proximity to final assembly operations can certainly reduce both transportation costs and the cost of communication/coordination – unless of course something happens to the region where your suppliers are clustered.

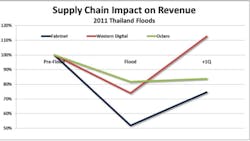

Western Digital was especially hard hit by the shock to its supply chain caused by the Thai floods, losing nearly 75% of its production capacity for several weeks. This one event caused WD to cede its number one market share position in hard disk drives to its arch rival Seagate, which experienced very little supply chain disruption from the event. According to iSupply analyst Fang Zhang, Seagate shipped roughly 46.9 million drives in the flood affected quarter versus Western Digital which shipped just 28.5 million. A relatively lean, low-cost, highly concentrated supply chain, in part, cost WD about $700 million in lost revenue. It nearly cost optical device firm Oclaro the company, as they saw supplies of product from Thailand dry up (no pun intended) for weeks on end, causing a nearly 50% quarter-to-quarter revenue contraction.

Lesson Almost Learned

I‘ve spent much of the past few weeks traveling in the U.S. and Europe meeting with a number of OEMs and manufacturing services providers getting their views on the evolution of manufacturing, outsourcing and supply chain management over the next 5 to 10 years. This endeavor was far from a scientifically rigorous study, but the anecdotal observations obtained were pretty informative.

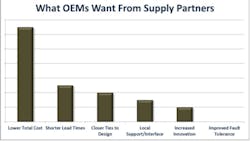

It comes as no surprise that most OEMs see their futures as being very similar to today, where cost and delivery are seen as 90% of the supply chain management equation. This reveals a lot about how OEMs see their competitive landscape, and of course even more about where incentives and bonuses are targeted for supply chain executives. It also reveals a lot about both statistics and economics. There seem to be relatively few supply chain executives out there that are willing to trade in an extra 1% to 2% in permanent, structural supply chain costs as a hedge against a low probability event that may temporarily add 30% to 50% to supply chain costs – or worse yet, that may dramatically reduce or even stop shipments of products to customers. Many companies do not spend much executive mindshare planning for events they see as improbable until an improbable event bites them right in the earnings.

Perhaps we can all learn a bit here from physicians and the research of the esteemed scientists at Portland State and the University of Western Australia. Maybe a little bit of structural fat is not necessarily a bad thing as it offers some buffer against external shocks that can be ultimately devastating. And what else might we infer from their research? Their findings that the fattest of the fat are at the greatest risk of mortality I think most of us already knew that to be true about supply chains. Really fat supply chains have long been linked to mortality of bonuses.

Contributing Editor Ron Keith is chief executive officer for Riverwood Solutions, a supply chain consulting and managed services firm.

About the Author

Ron Keith

Chief Executive Officer

Ron Keith brings more than 24 years of operations experience to Riverwood Solutions including engineering, manufacturing and executive management positions at Westinghouse, Wavetek, Rockwell, Alcatel and Flextronics International. Ron has a reputation as an innovator, team builder, creative problem solver and strategic thinker who delivers straight talk and strong results to Riverwood's clients. He has run international EMS operations with annual sales in excess of $1.4B and has managed manufacturing, product development, and program management personnel in numerous countries.

Ron has advised more than four dozen companies on their manufacturing operations, supply chain, and outsourcing strategy including more than a dozen Global Fortune 500 companies. He has previously consulted for four of the top 10 EMS (Electronic Manufacturing Services) companies and has advised hedge funds, private equity funds and strategic investors on a number manufacturing services related investments. Ron has published more than 30 articles on various manufacturing, technology and business related topics including strategy, operations, quality management, technology trends, and supply chain management.

Prior to founding Oreamnos Partners and Riverwood Solutions, Ron served as Vice President and General Manager at Flextronics International, where he started and ran several divisions in both the EMS and ODM (Original Design Manufacturer) spaces during his more than eight year tenure. He worked with, and ran manufacturing operations for, a number of leading OEMs at Flextronics including Cisco, Motorola, JDS Uniphase, Nortel. W.L. Gore, Kyocera and others.

Ron has undergraduate degrees in both Electronic Engineering and Manufacturing. He received an MA in International Management and an MBA in Operations Research from the University of Texas at Dallas, where he also completed the majority of coursework towards a Ph.D. in Organization, Strategy & International Management (OSIM).