Building a Responsive Semiconductor Supply Chain Is Tougher than You Think

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

The U.S. ranked fifth in semiconductor fabrication capacity in 2019, accounting for only 11% of worldwide capacity. Expanding semiconductor fabrication capacity can secure the development of other emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, 5G communications and quantum computing in the U.S.

Various capacity expansion plans have been put in place in January 2022. Intel announced its plan to invest $20 billion to build two semiconductor plants in Ohio on January 21. Four days later, the U.S. House of Representatives leaders unveiled a bill (the America Competes act) aimed at supporting the U.S. chip industry, including $52 billion to subsidize semiconductor manufacturing and research.

These responsive developments are necessary to revitalize the U.S. semiconductor industry and the manufacturing sector that relies on semiconductors. Currently, global chip shortages disrupted car manufacturing in the U.S., reduced the supply of many electronic devices, and hindered the 5G rollout around the world. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo commented that many U.S. manufacturers have just a few days of semiconductor inventory.

In addition to Ohio, Intel has two additional plants under construction in Chandler, Arizona since 2021, and these two new plants scheduled to begin production in 2024. Besides Intel, GlobalFoundries announced its plan in 2021 to double its fabrication facility in New York. Also, Taiwan’s TSMC begun its construction of a new nano-chip factory site in Phoenix, Arizona. These efforts will increase the semiconductor fabrication capacity in the U.S. multiple folds from 2024 onwards.

Is It Enough?

Will the $52 billion bill and these expansion plans secure chip shortages in the long term?

These capacity expansion plans are important first steps, but not sufficient. To develop a sustainable semiconductor ecosystem in the U.S., additional efforts are needed to secure the capability and capacity of all the major players. And the Biden administration needs to identify and secure all the links of these supply chains. I suggest three specifications.

Identifying Shortages

First, semiconductors can be classified into four major product groups based on their function: microprocessors and logic devices; memory; analog; and optoelectronics and sensors. Different types of chips have different supply chains. In September 2021, the Department of Commerce launched a semiconductor request for information (RFI), asking producers and consumers to share supply and demand information about different types of chips.

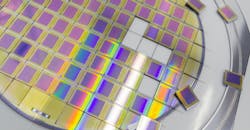

The semiconductor RFI report revealed that, across different types of chips, the bottleneck appears to be wafer production capacity. Also, other input materials such as diodes, capacitors and substrates have been in short supply since 2020. Therefore, it is essential for the U.S. government to work with industry to develop short-term plans to overcome the current shortages and long-term plans to secure the semiconductor supply-chain operations and ensure sufficient supply.

Prioritizing Substrates

Second, it is important to secure major input materials for semiconductor supply chain operations in the U.S. Silicon wafer production can be relatively easy to expand in the U.S. Besides silicon wafers, however, it has recently come to light that substrates used in some of the most advanced chips are in short supply, and could remain in short supply for years.

Substrates connect chips to the circuit boards. Because substrates are relatively simple, they have been a less visible part of the global semiconductor supply chains.

Chip manufacturers such as Intel and AMD enjoy a gross margin of over 50%, whereas substrate manufacturers such as Unimicron Technology in Taiwan and Ibiden Co in Japan earn just above 10% gross margin. Because of high fixed costs and low profit margins, most U.S. firms outsource substrate manufacturing overseas. While U.S. chip makers are placing future substrate orders, the Biden administration should provide financial incentive for substrate suppliers to expand their operations in the U.S.

Securing Needed Equipment and Fostering Research

Third, to ensure U.S. will continue to lead in the semiconductor research and development, the Biden administration must look at the availability of the equipment needed to manufacture semiconductors. Leading U.S. semiconductor equipment firms such as Applied Materials and Lam Research can play an important role in expanding R&D activities by collaborating more with various universities in the U.S. Also, the U.S. government should provide incentives for ASML (a Dutch semiconductor equipment firm) to expand their operations in the U.S., because ASML has the leading lithography technology for printing circuitry using extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light that is critical for nanochip development.

Ultimately, the U.S. government should work with the private sector and universities to develop a new consortium, or to strengthen the research consortium SEMATECH that was once supported by the Congress through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). A research consortium could foster new capabilities for developing innovative semiconductor technologies in the future.

By creating new research and development capabilities and by expanding production capacities of the entire semiconductor supply chain, the U.S. can regain its glory. After all, the semiconductor was invented in the U.S.

Christopher S. Tang is a University Distinguished Professor and Edward W. Carter chair in business administration at the UCLA Anderson School of Management.