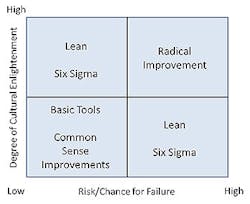

Radical Improvement – A significant change to a process utilizing new technology and/or innovative methodologies that results in an improvement to customer satisfaction so dramatic that demand for the product or service increases.

I can remember the day I shut down a major GE manufacturing plant like it was yesterday. The year was 1988 and I was working as a process engineer on the shop floor of building 5 in Appliance Park where we made refrigerators.

There was a difficult step in the assembly process that generated several quality issues, line stoppages and significant non-value added cost. The cross functional team I was leading was determined to come up with a better process to eliminate all of the hassles this step caused. So, with help from the operators, we researched a new, innovative way to simplify the process and greatly reduce any chance of error. This required a slight design change as well as an entirely new way to perform this operation, including the use of a new piece of equipment.

We followed the Plan-Do-Check-Act methodology and ran several pilots before putting the changes into place. After all of the trials met or exceeded our expectations, the day finally came to make the changes permanent. For five hours, everything went without a hitch. The operators embraced the improvements, the operation was much easier to perform, and the quality issues went away entirely.

Then, disaster struck. All of a sudden, every refrigerator was being rejected and the line had to be shut down. It turns out that if several components happened to be on the highest end of the specification and certain other components were on the lowest end of the specification, a tiny gap would form that allowed the foam insulation to leak resulting in a major need for repair.

The project team quickly worked to put a temporary fix in place so we could get the line back up and running. However, several hours of production had already been lost.

The plant manager was furious. He came out to the shop floor and chewed me out for what seemed like an eternity. Fortunately, my team had my back and explained that if he was going to reprimand me, he had to do the same for each of them as well. That would have been difficult to do since we had representatives from each department as well as a couple of participants who were on the plant manager’s staff.

Finding A Permanent Fix

The team understood that we needed to go back to “Plan” and figure out what happened. After a couple of minor changes (and many more pilot runs), we were able to put a permanent fix into place. The company saved a significant amount of cost and one of our top quality issues went away.

Once the plant manager realized that the team had done everything possible to mitigate the risk (and how much of a radical improvement resulted in the change), he apologized and the team got publically recognized. This opened the door to more teams being formed and further improvements taking place.

If the plant manager had not backed down, the tone would have been set that no risk would be tolerated no matter how much due diligence was performed.

The example that follows may shed further light on the role culture plays in promoting radical improvement.

Doug started the meeting promptly at 10:00 a.m. Being a manufacturing engineer required a degree of precision, and Doug liked things starting on time. This was the third time that this group had convened for one of its weekly meetings. Doug was pleased with the team and its progress. It was a good mix of operators, engineers, supervisors and various other functional representatives.

“So, I believe at our last meeting,” said Doug, “we were leaning toward breaking the bottleneck on production line No. 6 by submitting a request to buy another machine like the one we already have. That would double the output at that step of the process and should give us plenty of capacity for the next couple of years.”

“I have a concern I would like to raise,” said the representative from the sales and marketing group. “The feedback from our customers has been extremely positive for this product. Sales orders are coming in faster than any of our forecasts had projected. We are now thinking that our demand may double in the next six months and then double again within a year. So, adding one more machine may only buy us less than a year’s worth of time before we are back here again.”

“Hmmm…,” said Doug. “We could request two additional machines, but I don’t think there is room in our factory for both. Our plant is jammed full, and we are land locked so expanding our manufacturing footprint isn’t feasible. This is a proprietary operation, so outsourcing is not an option. If we continue down this path, we may be forced to move the entire operation to a different plant site.”

“I don’t think we are trying hard enough,” said Mary, one of the shop floor team leaders. “I mean, we have a lot of brain power in this room, and it seems to me we should be able to come up with a more innovative solution than just replicating what we already have. Isn’t there some better way to do this operation that we are missing?”

“The first step in the machine is heating the material to the correct temperature before moving the part to the next step,” said the person who runs the process being discussed. “It seems to take forever to complete that step, and I am sure that is what slows the entire operation. Maybe we could find a way to add more heat to make that step go faster.”

“I worked in a different industry a couple of years ago,” said one of the engineers. “And they used a newer technology to cut the time it takes to heat this same type of material. If we put something like that into place, we may be able to increase the output without buying another machine.”

Doug went to the process map the team had created and circled the heating step. “I don’t know if a different technology will work with our process, and we need to verify that speeding up the heating step will increase the throughput.”

“Well, why don’t we call up the company that manufactures this new heating technology and get their input,” said Mary. “It can’t hurt anything to ask the experts a few questions.”

Doug and the rest of the team agreed, and they developed a list of action items and concluded the meeting. Over the next month, they experimented with the new technology and were pleasantly surprised by the results. The output of the process would increase by over 400% and there were no quality or design integrity concerns. The cost of adding the new technology was actually a little less than the original idea of buying another machine. Now all they had to do was get management’s approval.

“Wow, that was an impressive presentation,” said the director of engineering at the management review of the team’s recommendations. “This new technology sounds promising.”

Promising, But No

“Yes, it does sound promising,” said the operations manager with a sigh. “However, it seems that I recall we tried something similar a while back, and it didn’t work then, and I don’t think it will work now.”

“No,” said Doug. “That was a different technology, and we stopped the project due to the high cost.”

“Oh, I see,” said the operations manager. “Well, I am not comfortable using this new technology without extensive research and development.”

“My folks have been intimately involved, and they tell me there is very little risk,” said the director of engineering. “In fact, they discovered that other industries have successfully utilized this same process change for several years. I would be willing to approve the technology.”

“Even with your endorsement, I think we need to put in many more months, maybe years, of research before we discuss this idea any further,” said the operations manager. “And we don’t have time to wait that long to break this bottleneck, so I will approve the team’s back-up idea and purchase another machine like the one we have now. I have been informed that we can acquire a new machine and have it installed by the end of this month. I want to thank the team for your hard work and appreciate all of the thought that went into your recommendations. Now, we all better get back to work so we can meet our customers’ needs.”

The room began to empty out, but Doug continued to sit at the conference room table staring at the floor. Before long, Doug and the operations manager were the only two left in the room.

“It takes six months to get one of those machines,” said Doug as he continued to stare at the floor. “Six months.” He quickly stood up and glared into the operations manager’s eyes. “That means someone had to place the order to buy the machine several weeks before my team got together for our first meeting!”

“Calm down, Doug,” said the operations manager. “I guess you would know that bit of information in your role as a manufacturing engineer. But no one else knows, and if you want to keep your job, I expect that information to stay between the two of us.”

“Why then did you ask me to pull this team together?”

“Well, the employees now feel that they were a part of the final decision so I expect them to buy into the plan. Plus, the corporate folks said I needed to get more workers involved on teams. I never expected that they would actually come up with some new ideas.”

Doug felt sick to his stomach as he left the room. “How will I ever trust management again?” he thought.

And another radical improvement idea that could have been a game changer ends up on the cutting room floor.

For example, one company requires 15 managers to sign off on any change to the process. Fifteen! What are the chances that anything of significance will change? Of course, the risk has to be managed and the team must follow a well-defined methodology. But the rewards can be significant.

Dr. W. Edwards Deming spoke often about the need of using “profound knowledge” when making radical improvements. A team of insiders in a company doesn't know what it doesn't know, so it may be necessary to invite people from outside the organization to help the team generate some new ways of thinking. This could be employees from the corporate office, from a different business division, from a supplier or even a consultant who may be able to share insights from other companies or industries. Recently I was able to help a call center of customer service representatives. We were able to implement many of the same lean techniques used in a manufacturing operation to reduce the average call hold times from several minutes to seconds.

One tool that can be used to help identify, plan for and potentially reduce the risk associated with design and process changes is known as a failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). An FMEA requires a team of people to come together to brainstorm a list of potential problems that could occur when making a change/improvement.

Each of these potential problems then is assigned a score of 1 (Low) to 10 (High) in three categories. First, what is the impact if the problem does occur (Severity)? Second, what is the probability that the problem might actually happen (Occurrence)? And third, what is the chance of detection if the problem is created (Detection)? The three scores then are multiplied together to get an overall score of 1 to 1000. This allows the team to prioritize its concerns as well as track progress toward reducing or eliminating each potential problem.

When a team uses tools such as completing a FMEA and follows standard change methodologies (such as Plan-Do-Check-Act or Six Sigma’s DMAIC), it can build confidence in the process and lessen the chance of something going wrong. Of course, it all begins with company leaders who support a culture of teamwork and empowerment that ignites the passion for radical improvement. The rewards can be a game-changing experience for the customers and may help secure the company’s future.

John Dyer is president of the JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 28 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. Dyer can be reached at (704)658-0049 and [email protected]. Linked In Profile: http://www.linkedin.com/pub/john-dyer/0/646/75a/ He is on Twitter: @JohnDyerPI.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.