Confusion Over Standards: Limits or Basis for Innovation?

The word “standards” evokes images of bureaucracies full of rules, specifications and procedures that people must follow like the law (another set of standards) or else. We are victimized by endless standards and “ignorance is no excuse.”

As an undergraduate engineering student I spent a term in the offices of a nuclear power company writing standards. I sat at a desk, with a typewriter, and nuclear engineers fed me information while I wrote the standards. Standard 300.47.3.1. I had never been to a nuclear power site and had no idea what I was writing about, and I am pretty certain nobody at the site had memorized the tens of thousands of standards. They were aimed at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission who audited the company so we could prove we were safe. To the best of my knowledge pieces of paper never prevented a nuclear crisis.

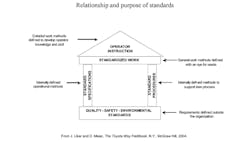

In The Toyota Way Fieldbook we tried to clear up some of this confusion. We used a house to illustrate the various types of standards (see diagram below). The foundation of quality, safety and environmental standards generally are defined by outside organizations such as the government agencies and Consumer Reports that evaluate the product. They are generally interpreted by internal staff organizations, often at the corporate level, and are non-negotiable. Standard specifications for the product and process usually come from engineering, and standard procedures come from a variety of specialty departments, like inventory buffer quantities from production control and disciplinary procedures from human resources. These also are to be followed as written unless you can get explicit permission to relax or change them.

Toyota has all these standards which fit the image of a traditional bureaucracy from the viewpoint of those working on the shopfloor—rules, rules and more rules coming at us from every direction. But in a lean system there are two major differences. First, there is an explicit recognition that the work group led by a group leader have responsibility for turning all of these rules into action within their area of control through standardized work. Second, those making the rules are expected to spend time on the shop floor (at the gemba) deeply understanding the impact of the standards on the work groups.

Standardized work is the method used to define work tasks with the least amount of waste. It incorporates standards from many different specialists. There are two levels: First, a high-level description of the steps, time each step takes, and how the work flows illustrated in a diagram called the “standardized work sheet.” Second, this is broken down further for training purposes into operator instruction sheets which specify subtasks, key points on how they should be performed, and reasons for the key points. The key points include quality, safety, and some product and process specifications, along with knacks learned over time. This is where the rubber meets the road and many of the standards come together here in how the work is actually performed.

Since Toyota’s DNA is based on continuous improvement and respect for people, they want the minimum critical specifications and they want the work groups to have as much control as possible over improving on the standards. Thus, standardized work is owned by the work groups who are encouraged to continually improve quality, safety, productivity, cost and human resource management. They must meet the external and internal technical requirements, but have considerable freedom over how they perform the work.

As Henry Ford put it in his prophetic book Today and Tomorrow, “If you think of “standardization” as the best you know today, but which is to be improved tomorrow—you get somewhere. But if you think of standards as confining, then progress stops.” Properly used standards become a basis of comparison between what you are trying to achieve and where you are.

The standard is never perfectly achieved every time, but with improvement over time it is possible to reduce the variation in processes and then tighten the standard, raising the bar for performance. This is in fact the basis for continuous improvement. Imagine if standards facilitated innovation instead of stifling it!

___________________________________________________________________________

Liker Leadership Institute (LLI) offers an innovative way to learn the secrets of lean leadership through an online education model that is itself lean, and extends that lean education far beyond the course materials. Learn more about LLI's green belt and yellow belt courses in "The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership" and "Principles of Lean Thinking" at the IndustryWeek Store.

About the Author

Jeffrey Liker Blog

CEO

Dr. Jeffrey K. Liker is Professor of Industrial and Operations Engineering at the University of Michigan and a professional speaker and advisor through his company Liker Lean Advisors (LLI), an organization established with a network of associates to teach and consult in the Toyota Way. He is also CEO of Lean Leadership Institute, the home for online courses beginning with The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership.

Dr. Liker is author of the international best-seller, The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest Manufacturer (McGraw Hill, 2004), which speaks to the underlying philosophy and principles that drive Toyota's quality and efficiency-obsessed culture. The companion (with David Meier) Toyota Way Fieldbook (McGraw Hill, 2005) details how companies can learn from the Toyota Way principles. His book with Jim Morgan, The Toyota Product Development System (Productivity Press, 2006), is the first that details the product development side of Toyota. His articles and books have won nine Shingo Prizes for Research Excellence and The Toyota Way also won the 2005 Institute of Industrial Engineers Book of the Year Award and 2007 Sloan Industry Studies Book of the Year. In 2012 he was inducted into the Association of Manufacturing Excellence Hall of Fame. He is a frequent keynote speaker and consultant.