If Dr. Deming were alive today, would he embrace being a certified Six Sigma Black Belt (or in his case a Master Black Belt)? The answer to this question is impossible to know for certain. However, there are several clues in his teachings that could help shape opinions on what the answer might be.

Dr. W. Edwards Deming was first and foremost a statistician. His degree was in electrical engineering and he eventually became a professor of statistics at NYU. He used his understanding of mathematics to develop sampling techniques that allow for accurate predictions of a whole based on the results of a few. In the late 1940s, he was asked by the U.S. government to help out with a census of the Japanese population. While there, he introduced the Japanese industrial executives to various quality improvement tools (such as statistical process control) and leadership techniques (His 14 Principles of Management and 7 Deadly Diseases). This, of course, led to the successful turnaround of many Japanese companies.

Why Dr. Deming might not have supported being a Six Sigma Black Belt

From Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s 7 Deadly Diseases of Management: Emphasis on short-term profits: short-term thinking fed by fear of unfriendly takeovers and pushed from bankers and owners for dividends.

When one hears the term “Black Belt,” images of expert martial artists comes to mind; an elite group of people who have worked hard to master their craft. One of the mistakes many in upper management make when it comes to Six Sigma is that they send a handful of their best employees out to get their Black Belts and then think that they have done their part without bothering to try and learn themselves. Once their employees achieve certification, the company executives usually want a quick return on their investment. This can have devastating results as illustrated in the following example (based on an actual project).

Doug silently closed the door to his office, sat down behind his desk and reexamined the chart on his computer screen. “What have I done?!?” he thought as he closed his eyes to try and figure out what to do next.

Three months earlier, Doug was elated when he received his Six Sigma Black Belt certification. He had gone to several training sessions and completed a simple, yet impactful project in order to achieve this career goal.

“Congratulations Doug,” his manager told him when he returned. “Now, we need to put your new knowledge to work so you can help us achieve our objectives. I want you to take a look at our order entry process. One of our leading customer complaints is that it takes an excessive amount of time to place an order over the phone.”

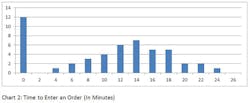

Doug set out to demonstrate to his boss that the tools and methodology he learned would prove to be beneficial. He formed a team of several order entry operators and began using the DMAIC methodology to help figure out what was causing the excessive order entry times. Once some data were collected, he put together the following chart showing the amount of time it took to enter an order.

“Wow!” said Doug at one of their meetings. “It looks like our customers spend an average of 14 minutes on the phone to get an order placed. But look at the range. It could take as little as four minutes but could take as long as 24 minutes. This seems excessive.”

“That does not surprise me,” said one of the order takers. “Our computer systems are extremely slow, especially when we are dealing with a high volume of calls.”

“Yeah,” said another. “It gets so bad sometimes that I find it easier to look up the part numbers in our catalogues. This can take quite a long time, especially on complex orders. We tried a while back to add more operators, but that just slowed the system down even more.”

After several weeks of meetings and analysis, the team exhausted all avenues with the exception of the most obvious solution: upgrading the computer systems to speed up the processing times.

Doug presented all of the data, analytical work and recommendation to the company leaders.

Where are the Cost Savings?

“I am extremely disappointed,” said the company CEO after Doug’s presentation. “We invested in your Six Sigma training in order to see a quick cost savings, and you come in here asking for us to spend more money to fix this problem. Clearly, you did not learn what was taught, or maybe this whole Six Sigma thing is a bunch of smoke and mirrors.”

“Hey, let’s go easy on Doug,” said his boss. “This is his first major project and maybe he did not understand what we were looking for. Now he knows, and he can go back to his team and they can come up with another approach.”

“I like to give people a second chance,” said the CEO as he glared at Doug. “Hopefully our expectations are clear… and if you can’t meet them, then maybe we will have no other choice but to find someone who can!”

Word spread quickly about what happened in the meeting and how Doug’s job was now on the line. Several of the order entry operators met in the break room to discuss what happened.

“We have got to come up with a way to cut the order entry times,” said one of the operators. “I like Doug, and I think he is really trying to do the right thing. We need more people like him, not less.”

“I know what we can do to bring the times down,” said another operator. “But we can’t tell anyone, especially Doug.” The operators discussed the idea and agreed to give it a try.

Over the next week, the average order entry times began to drop even though the volume of calls stayed the same. Doug was amazed at the new times being reported, and he asked his team what had changed. All they would say was that they "had his back" and were working on a new process that was much faster.

“Now this is the kind of improvement we were looking for!” said the CEO after Doug presented the new average times. “The question now is how is this going to result in a cost savings for the company?”

“Well, we have two choices,” said Doug’s boss. “We could share with our customers that our times have improved and use that to try and generate more business. Or, we could lay off several of our order entry operators and let the average times go back to what they were when the project started.”

“We need to meet our numbers this quarter, so let’s go with the layoff option,” said the CEO.

Doug headed back to his office in stunned silence and noticed that the latest charts showing the order entry times were sitting in his e-mail inbox. He was shocked by what he saw when he opened the file.

“What have I done?!?” he thought as he was overcome with a sense of despair. “Now I know how the lower average times were achieved. The operators have been doing quick hang ups on the customers and now we are about to lay off several of them. If I tell my boss, I am sure I will be fired for letting this happen and I really need this job. How will I be able to survive this mess?”

When a potential client asks me to help with a Six Sigma initiative, I ask them five questions. One of the questions is: Does your company leadership team understand and embrace its role, and are they willing to learn what Six Sigma is all about? If the answer to this is no, I usually decline the request since the probability of success is extremely low. (I have also had the privilege of working with several companies where the leadership team was engaged and willing to learn, and the improvements were dramatic) So, I believe Dr. Deming would not support a company launching a Six Sigma Black Belt certification process without upper management’s full involvement, understanding, and support. This would include the leader’s commitment that the methodologies need to focus on driving superior customer satisfaction vs. short term cost cutting.

From Dr. Deming’s 14 Principles: Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team, to foresee problems of production…

Another concern Dr. Deming might have had with some companies’ Six Sigma approach is the way they structure their improvement organizations. Several companies have set up an organization structure that separates their Six Sigma resources from the rest of their employees. This creates artificial barriers that can result in additional company silos.

For example, one company started on sound footing by setting up the following organizational structure:

The Six Sigma Black Belts prioritized their projects based on the needs of the plant and its customers, and they were given direction and support by the plant manager. They worked closely with employees at all levels of the organization. Everyone in the company understood that the Black Belts were working hard to help them control and improve their processes.

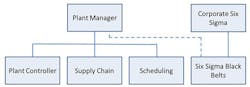

However, a year later, the corporate Six Sigma leaders were able to successfully make the argument for a slight change to the organizational structure.

The impact of this change was dramatic and immediate. The Black Belts began to take their orders from a corporate leader with a new emphasis on different priorities that did not support the strategic vision that the plant leadership team had agreed to implement. The Black Belts also began to withhold sharing their knowledge with anyone else (the ‘knowledge is power’ syndrome). This resulted in several projects failing as they alienated themselves from the rest of the plant employees.

This can happen with any improvement initiative, of course. However, the problem can be exacerbated if the certified Black Belts begin to think that they are somehow a cut above others in the organization. A way to combat this would be to encourage all Black Belts to spend time sharing their knowledge with others. All employees in the organization need to understand the Six Sigma philosophies, methodologies and tools in order for the company to realize its full potential.

Why Dr. Deming might support being a Six Sigma Black Belt

I believe Dr. Deming would be pleased with the spread of statistical knowledge as more employees learn the Six Sigma tools and techniques. Maybe not for the reasons everyone might think, however. Dr. Deming fought hard to change the culture that was prominent in the mid to late 1900s. He was agitated by management always blaming quality problems on the workers when in fact most of the responsibility rested on the shoulders of the company leaders. His understanding of statistics helped him realize that no worker could be successful if management provides a broken process that is not capable of making good parts all of the time (the foundational meaning of his red bead exercise). One way of explaining this would be to give someone a six-sided die and ask them to roll it every 30 seconds. If they roll a six, would it make sense to yell at them for incompetence? Clearly, it does not. Yet, managers have been blaming poor quality on employees for decades even though managers are the ones who provided bad materials, defective machines and inferior tools. Dr. Deming spoke often about how much this bothered him.

So, as more leaders become exposed to Six Sigma, maybe it will continue to sink in that when problems occur, they need to change their focus away from blaming the employees and instead focus on designing more robust processes. This can be accomplished by teaming up with the workforce and providing them with the knowledge, tools and resources necessary to control and improve their processes. The culture change required to make this happen would support the vision Dr. Deming portrays in his 14 points of management.

Lean vs. Six Sigma

There is a lot of discussion about the use of lean vs. the use of Six Sigma. I think Dr. Deming would have said that this is a most ridiculous debate. I am not sure how any manufacturing facility could fully implement lean without reducing all sources of variation using Six Sigma, so both are essential to a sound continuous improvement policy.

IndustryWeek conducts a “Best Plants” competition each year and they compile quite a bit of data from all of the submittals. Over the past five years, 99% of all submittals claim to be implementing lean in a “significant” way. Only 53% claim to be employing Six Sigma at this level. My fear is that even the 53% number may be over inflated.

I have visited several plants that advertise that they are fully engaged with Six Sigma. However, when talking to the people on the shop floor in some of these plants, few workers exhibit knowledge of the most basic Six Sigma principles, such as the difference between common and special causes of variation or the capability of their process (Cp and Cpk values). These plants may have several Six Sigma Black Belts and may even have a corporate Six Sigma team, but the knowledge has not propagated to the workers who control the processes or to the executives who lead the company. I think this would have greatly concerned Dr. Deming.

Would Dr. Deming Have Been a Black Belt?

I believe Dr. Deming would have fully embraced the implementation of both lean and Six Sigma. However, he would have wanted everyone, at every level in the organization to be fully involved in every aspect. A company leadership team might be tempted to train a few Six Sigma experts and then wash their hands of any responsibilities. The leaders might also believe that Six Sigma is too complicated for the average worker to comprehend. I do not think Dr. Deming would have supported this premise. (For example, he came up with effective teaching tools such as helping people grasp what variability looks like by dropping marbles through a funnel.) It is my opinion that he would have had enough reservations about the potential lack of company leaders’ involvement and the possible segregation of employees based on the color of their belt to not fully embrace the Black Belt certification concept.

John Dyer is president of the JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 28 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. Dyer can be reached at (704)658-0049 and [email protected]. See his LinkedIn Profile. He is on Twitter: @JohnDyerPI.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.