Does Management By Objectives Stifle Excellence?

From Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s 14 Points: Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute leadership. Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership.

Why do some companies struggle when it comes to implementing lean and Six Sigma? A critically important step toward a successful improvement implementation is to get buy-in and support from top management. However, do the company’s leaders embrace the improvement initiatives enough to make radical changes in how they operate? What if this meant throwing out their entire way of measuring the success or failure of their employees?

One of Dr. Deming’s more controversial points in running a company is listed above (in italics). When company executives are surveyed about Dr. Deming’s 14 points, they tend to rank this point at the bottom of the list in both importance and ability to implement. U.S. companies have relied on using some sort of Management by Objective (MBO) type system for so long, it is difficult to think about alternatives.

Let’s explore the damage MBOs may have on a company’s ability to improve and what might have been behind Dr. Deming’s thinking when he included this in his 14 points. (The example that follows is based on real-world experiences.)

Jim Smith, one of the company’s plant managers, was feeling pretty good about his upcoming performance review with his boss. Jim had managed to meet every one of the objectives that was set a year earlier at his last review. He also knew that the next 12 months were going to be difficult since they were expecting several new product launches, so he was hoping to negotiate easier goals for the next year.

“Jim, come on in and have a seat,” his boss said as he was motioning to an empty chair. “I have been looking over your performance objectives for this past year, and frankly, something does not add up. It appears that you managed to meet all of your goals, and while your plant did perform slightly better, it seems that several other plants in the company far exceeded your improvement. Why do you think they were able to do so much better?”

“I’m not really sure,” said Jim as his ego was somewhat deflated. “I mean, we improved in every category that we measured. Our quality yield, for example, went from 92% to 92.6%. Our goal was to get to 92.5%, so we feel pretty good that we not only met the goal but exceeded it slightly.”

Jim’s boss did not look happy. “Our plant across town that is managed by Mary Jones started the year with a quality yield that was also 92%, but they managed to increase it to 99.3%. They had similar improvements in several other categories while also managing to keep their costs down. Before we set next year’s objectives, I want you to go meet with Mary and find out what they are doing to achieve those kinds of results.”

What Do You Do Differently?

So, Jim set up a meeting with Mary Jones. He had been to Mary’s plant several times but had not really paid much attention to what they were doing there. He knew that they made similar products, so it would be difficult to rationalize the gap in their performance on the product or the process differences.

Mary welcomed Jim and asked him to join her in her plant’s operations conference room. She also invited her leadership team, and they quickly introduced themselves as Jim got settled in for the meeting.

“I hope you don’t mind if I take a few notes,” said Jim. “I have been challenged with the task of trying to understand how your plant is performing so much better than mine. You must set much higher goals for your workers to get the kind of results I have heard about.”

“No, actually we have not set goals this entire year,” said Mary. “I decided to hold back on sharing the goals our boss gave us, and as the year progressed we have slowly gained his trust to try this approach. Don’t get me wrong. We still measure everything we did before and track improvement trends, but we don’t limit our thinking by setting artificial goals.”

“Limit your thinking? What do you mean?” asked Jim.

“A little over a year ago, my leadership team and I decided to go through some training and team building together,” said Mary. “One of the activities in the class was a business simulation. The class was split into two teams and we were challenged to figure out how to improve the simulated business process in order to get the cost below a certain target. The team I was on calculated exactly how much product we needed to sell to hit the cost goal and then we designed our process to make that number. We ran the simulation and met all of the goals and thought that we had done very well. Then we found out that the other team decided to ignore the goal and design their business process to reduce the cost as much as possible. They got very creative with the process design and came up with several innovative ideas for dramatic improvement. Their team ended up selling twice as much product and reduced their overall cost by over 50% of what we had done. That was a real ah-ha moment for all of us.”

“If there is a fear that goals could hamper your ability to dramatically improve, then why not set the objectives very high to try and motivate your employees?” said Jim

Mary’s procurement manager spoke up. “I worked for a company that once tried to use stretch goals, and it absolutely killed morale. In many cases, the stretch goal became THE goal, and your performance would get downgraded if you did not hit the stretch goal. And, if you did hit the stretch goal, then you clearly did not stretch far enough. So, either way, there was no way to win.”

“As we started discussing the impact goals have on the way we do things,” said Mary, “we began to realize how our objectives were causing us to do really stupid things. It became clear that people were manipulating data to hit their targets instead of doing any real improvement.”

“Manipulating data?” exclaimed Jim. “You mean like cooking the books?”

Lots of Game Playing with Data

“No, nothing that dramatic,” said Mary. “But there were a lot of games being played. I will give you an example of how easy it is to manipulate data. How many in this room would rather eat liver instead of eating glass?” Everyone’s hand went up. “So, after this little survey, I can now truthfully say that 100% of the people surveyed would rather eat liver over every other choice. Not exactly telling a lie but not really representing the truth either.”

“We also discovered that how we measured people’s performance was hurting our improvement efforts,” said the customer service manager. “One of our production manager’s main goals was to keep his employees 100% utilized. Even though he verbally supported our improvement efforts, he blocked most of the lean initiatives. It turns out that he was worried that if the team figured out a way to improve the process, they might get stuff done faster and if they ran out of things to work on, his employees’ utilization rate would drop and he would fail to meet his objectives.”

“Hmmm… well, that makes sense,” said Jim. “I guess I never thought about how goals can drive the wrong behavior. We recently had a situation where our engineering department figured out a way to reduce the time it takes to issue a drawing to manufacturing. They met their goal but it turns out that the changes caused major problems in manufacturing. The finger pointing increased and the silo walls between the departments became even thicker. “

“Yeah, we have had similar problems in purchasing,” said the procurement manager. “I have to admit that my team was so focused on meeting our price-cutting goals that we lost sight of what the total costs of our actions were. The quality and on-time delivery from our suppliers had gotten so bad that manufacturing had no chance to meet the customers’ needs.”

“What about the use of a balanced scorecard type approach to goals?” asked Jim.

“Keeping track of several metrics that balances all of our customer and business needs definitely helps,” said Mary. “And we do use a balanced scorecard to communicate to our employees how we are doing. However, we focus more on rate of improvement instead of setting arbitrary goals. We also celebrate when we hit certain milestones, but that is something we do as an entire plant.”

“We call them celebration points,” said the customer service manager. “For example, when we hit a quality yield of 95%, we bought everyone pizza. When we hit 99%, we bought everyone a steak lunch. We also now send a survey card to our customers with every order. Each time we get a card back with all excellent marks, we hold a random drawing and give away a major prize.”

“Our union has asked if they can add their logo to our survey cards and even asked if it would help to have several operators sign the cards,” added Mary. “Everyone in the plant is now really focused on the customer and is asking what they can do to help.”

“One other thing about MBOs,” added the production manager. “We soon realized that most of what we do takes a team effort. So, it really does not make sense to reward or punish an individual for certain performance metrics. For example, our on-time delivery performance began to suffer when our demand exceeded the capacity of our bottleneck (see Understanding the Demand/Capacity Curve). We realized that we had to work with our sales team to do a better job of planning and communicating our available capacity. This led to weekly sales and operations planning meetings, and our on-time delivery metric is back on track.”

“Exactly,” added Mary. “Once we realized that we are all in this together, we began to focus on initiatives that would improve our performance and give us a competitive advantage with our customers. I mean, if you really think about it, the entire company is being measured by our customer on a daily basis.

“Ok, I think I am getting the picture,” said Jim. “However, my concern is that if you don’t use MBOs, then how do you measure people and decide how to adjust salaries and bonuses or who to put on get well plans if they are not doing well?”

“Since we are mostly team based now,” said Mary, “it becomes apparent pretty quickly who is not pulling their weight or who is missing their deadlines. We now do a lot of 360 degree reviews where we get anonymous input from direct reports, peers and the leader. I mean, we ask our customers to fill out surveys of our performance, why not use a similar approach to providing feedback to our employees? Then, as leaders, it is up to us to help put together a plan to develop and improve the skills of those who are not rated very high. And frankly, some of our employees are not cut out to work in a team-based environment, and in those cases we have some tough decisions to make.”

So Jim went back to his boss and explained what he had learned. He then pulled his leadership team together and worked out a way to track and communicate their overall plant performance and develop a vision and strategy that would allow them to focus on achieving excellence in the eyes of their customers.

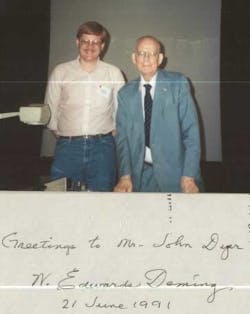

John Dyer is president of the JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 28 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. Dyer can be reached at (704)658-0049 and [email protected]. Linked In Profile: http://www.linkedin.com/pub/john-dyer/0/646/75a/

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.