Does Inventory Leanness Impact Performance?

Lean management programs are no longer restricted to a narrow segment of manufacturing companies. A wide range of medium-sized and large companies from different industries have deployed, to varying degrees, lean management programs. While the initial deployment of lean management principles in the United States focused on copying the Toyota Production System’s Just-In-Time concepts and practices, by the 2000s, several large firms began to introduce their own lean management systems. One of the central assumptions of the lean management efforts is that a leaner inventory level is better. This paper will explore what research has revealed about this question and also present some of the implications of the research findings for practitioners.

In this paper we will use the term lean management effort/initiative to describe the deployment of principles, methods, tools and techniques that enable an organization to eliminate wasted efforts and activities while delivering services that meet customers' expectations. Lean management approaches require that organizations document, assess, improve and manage the performance of production systems and resources. Inventory is one of the key resources that lean management programs target. This article will focus on this narrow, but important challenge of keeping inventory levels lean.

Given that the issue of inventory leanness has been important to managers, it is no surprise that early research studies focused on this area. Several studies that were executed in the 1990s surveyed manufacturing plants managers to explore the possible impacts of Just-In-Time programs and various kinds of lean programs of firm profitability or return on assets. With the exception of the work of Jayaram et al. (2008) and maybe a few others, most studies found a positive relationship between the deployment of lean management programs and firm performance/productivity.

These results suggest that more a firm deploys lean programs the better its performance compared to those with few lean programs or those without lean programs. One limitation of these survey studies was that they were based on subjective information and opinions. Secondly, such studies were sent to managers who may have had a personal bias/interest in having JIT programs’ effects be seen as positive. These limitations do not invalidate these survey-based studies; rather they suggest that the findings should be validated by different kinds of studies.

To learn more about the phenomenon, other researchers analyzed the panel data of public firms over time. Chen et al. (2005, 2007) established that across manufacturing firms that inventory and Work-In-Process (WIP) dropped between 1981-2000 (Rajagopalan and Malhotra, 2001). Furthermore, they found that inventory decreased for firms in the retail and wholesale trade industry segments. Given the nature of the panel data that was analyzed, the researchers could only make suggestions about reasons why inventory levels fell in the industries. Overall, it remained unclear in the study, if the drop in inventory level was associated with deployment of lean management initiatives or just an artifact of industry-wide market and economic factors. However, Chen et al. (2007) revealed that the drop in inventory levels was different across industries.

However, there are two concerns that are related to the extant panel data-based studies. The aggregate studies lump all firms in the industry together and ignore intra-industry differences. Should the performance of larger firms in an industry be compared directly with those of medium-sized ones in the same industry? This was one of the key questions that the academic research that we describe next, tried to answer.

About the Research

The research used panel data. Data on U.S. manufacturing firms were extracted from Standard & Poor’s COMPUSTAT database. The data for the study covered the period from 2003–2008. The data set included U.S. domestic manufacturing firms that were active, reported at the six-digit NAICS level and had positive numbers for sales and inventory. To be included in the study each U.S. manufacturing firm had to have more than 10 firm-level observations. Also, firms that had several missing data fields and incorrect data (such as observations with gross profit margins greater than 100%) were excluded. The resulting data set contained 7,804 firm-year observations from 1600 firms in 54 industries corresponding to an average of 4.88 years per firm. Findings of the study are described below.

Inventory Leanness Does Not Matter Everywhere

Given the seemingly convincing body of anecdotal and survey-based research relating to the positive impact that inventory leanness has on the performance of manufacturing firms, one would expect that having lean inventory would matter in most manufacturing industries. However, to our surprise in one-third of the 54 industries that were investigated, having lean inventory did not have a significant impact on performance (Eroglu, & Hofer, 2011). What this implies is the following. While the commitment of significant efforts and resources toward the deployment of lean inventory levels would yield good results in many industries, it will likely yield disappointing results in about a third of manufacturing industries.

In other words, the characteristics of industries are very relevant in determining if and to what extent lean inventory level initiatives would affect performance. Hence, we recommend that managers investigate the potential performance impacts of lean inventory before they commit to the deployment of company-wide lean inventory efforts. The kind of impact assessment could be done by assessing the performance impacts of lean inventory efforts of firms in their industry.

To be sure, having lean inventory would lower inventory carrying costs, however, the lowering of carrying costs could mean that the drastic increase of transportation, ordering and similar transaction costs. In which case, lean inventory may have limited positive impact on financial performance. A word of caution is needed here. Firms in industries, in which lean inventory may not have a significant impact on performance could still deploy lean management programs. However, such firms might want to focus on other aspects of lean management such as lean processes, redesign and reengineering efforts, which have the potential to raise capacity availability and capacity utilization in their firms.

Impact of Inventory Leanness on Performance Varies Across Industries

The theory of lean management posits that lean inventory is positively related to firm performance. However, this proposition does not tell us much about the pattern of the relationship. Ordinarily, people assume that the leaner the inventory the better the firm performance is expected to be. Published research show that, in industries in which inventory leanness positively impacts performance, the relationship between inventory leanness and performance varies across industries.

This finding has a number of implications. If a firm deploys lean inventory programs for its firms in different industries, the impact of inventory leanness on performance would be different for the efforts, all other things being equal. Hence, managers should be careful how they set expectations about the performance impacts of their lean inventory initiatives for firms which operate in different industries.

Furthermore, this finding also has implications for multi-industry firms in which a manager has to benchmark the inventory performance of firms which operate in different industries. Nothing would hurt a lean inventory initiative faster than the perception that management is unrealistic about the performance improvements that lean inventories are supposed to have. If a lean inventory program is being implemented in firms that are operating in different industries, management should find a way to set separate lean inventory to performance expectations for each of the initiatives.

The Relationship between Inventory Leanness and Performance is Non-Linear

The research also found that the relationship between inventory leanness and performance was non-linear in several manufacturing industries. This implies that, inventory leanness could have increasing positive association with performance up to a point and a decreasing positive or negative relationship to performance within a range of lean inventory level values. This finding is of practical importance for a number of reasons. First, it indicates that investment and effort in lean inventories could be expected to produce diminishing returns after a threshold point has been reached. In other words, after the optimum point of inventory leanness has been reached, leaner inventory is not better with respect to financial performance. It has been suggested in literature (Netland and Ferdows, 2014) that diminishing returns may occur during deployment of lean programs after a firm has exploited all the “low hanging fruit” or all the easier improvements.

Nevertheless, this paper argues that inventory leanness is not solely driven by this effect. Rather, it is argued that cutting inventory without regard for the external context of the industry and the internal performance characteristics of a firm could be expected to yield diminishing returns on performance. For example, if a firm sets is inventory leanness so thin that it is unable to respond to unexpected external demand without incurring excessive costs, such a level of leanness will create diminishing returns.

Similarly, an organization’s internal production system has an efficiency/quality characteristic. If the machine yields defective products 3% of the time, it would be impractical to cut extra inventory to 1% without first changing the quality performance characteristic of the system to 99%. In sum, a manager must find a way to judge the inventory leanness level that is appropriate for its industry and for her/his firm.

Changing How Inventory Leanness Is Measured

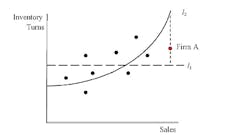

In general, managers have used simple metrics to measure inventory leanness. These metrics include the inventory-to-sales and inventory turnover. The primary advantage of such metrics is that they are easy to calculate and to deploy. However, due to the fact that these metrics lack a relevant anchor (e.g. sales-size) and are absolute in nature, they may lead to misleading conclusions. To illustrate the problem, consider the graph in Figure 1 below. It shows the relationship between inventory turns and sales.

Figure 1 shows two reference frontiers. Specifically, l1 represents the average industry turns as a reference frontier. If we compare the position of firms A and B, we will conclude that both of them have inventory turns that are better than the industry average. Hence, one might conclude that both firms are doing well with respect to the industry average. The problem with this conclusion is that the average inventory turns average is an aggregate measure. Hence, the metric conflate the performance of large and small companies.

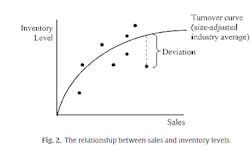

The study developed a new measure of inventory leanness that is called the Empirical Leanness Indicator (ELI). In contrast to simpler measures of inventory leanness, such as inventory-to-sales ratio and inventory turns, which do not account for the effects of economies of scale, the ELI specifically accounts for sales size. For example, all things being equal, firms with faster sales are expected to have faster inventory turns whereas firms with low sales will have lower turns.

In Figure 2, inventory level is plotted against sales. The ELI uses regression analysis to derive the ELI curve for each industry. The curve in Figure 2 represents the size-adjusted industry average inventory turnover. Deviations from the line are used as the basis for the assessment of inventory leanness. Firms below the curve are deemed to be lean because they hold fewer inventories than firms of similar size in same industry. Hence, the further down below the curve a firm is, the leaner its inventory. If one is seeking to an adjusted inventory turnover metric which derives its trade-off curve based on gross margins, capital intensity and sales surprise, we refer such a person to the work of Gaur et al. (2005).

Making the Metric Accessible to Managers

One of the significant hurdles of academic research is that of making it accessible to managers and practitioners. To enable managers to implement the ELI, we have created an online application that is easy to use. It is called the Inventory Leanness Benchmark (ILB). The data analysis can be done for over 50 manufacturing industries. In the intuitive app that has been provided with this paper, managers can enter the data for their firm for the year 2014 and the application will calculate and visually show them whether their firm has lean inventory or not.

We encourage managers to enter into the application the data of companies that they use as their benchmark their inventory performance. We hope that managers would try out the application and provide us with feedback about the thoughts that the paper provoked and the application ideas that the testing of the ILB generated in them. We will also like to hear from managers who would like to help us continue to develop the ILB.

Links to ILB Application:

NAIC Sectors 315 to 333: https://leanmanufacturing.shinyapps.io/manufacturing-benchmark315-333

NAIC Sectors 334 to 339: https://leanmanufacturing.shinyapps.io/manufacturing-benchmark334-339

About the authors: Adenekan Dedeke is a lecturer, Supply Chain and Information Management Group, D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University, Boston. He can be reached by email at [email protected] or by phone at 617-373-5521. Cuneyt Eroglu is an assistant professor, Supply Chain and Information Management Group, D’Amore-McKim School of Business, Northeastern University. He can be reached by email at [email protected] or phone at 617-373-8015.

REFERENCESChen, H., Frank, M. and Wu, O. 2005. What actually happened to the inventories of American companies between 1981 and 2000?, Management Science, 51, 1015-1031.Chen, H., Frank, M., and Wu, O. 2007. U.S. Retail and Wholesale Inventory Performance from 1981 to 2004, Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 9, 430-456.Eroglu, C., and Hofer, C. 2011. Lean, leaner, too lean? The inventory-performance link revisited. Journal of Operations Management, 29, 356–369.Gaur, V., Fisher, M., and Raman, A. 2005. An econometric analysis of inventory turnover performance in retail services. Management Science, 51(2), 181–194.Jayaram, J., Vickery, S., and Droge, C. 2008. Relationship building, lean strategy and firm performance: An exploratory study in the automotive supplier industry. International Journal of Production Research, 46(20), 5633–5649.Netland, T. and Ferdows, K. 2014. What to Expect From a Corporate Lean Program. Sloan Management Review Magazine. Research Feature, June 03.Rajagopalan, S., and Malhotra, A. 2001. Have U.S. manufacturing inventories really decreased? An empirical study. Manufacturing Service Operations Management, 3, 14-24.