“If one piece of candy gets past you and into the packing room unwrapped, you’re fired!” – I Love Lucy chocolate factory scene in the “Job Switching” episode, Season 1

In the late 1980s, I shared Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s eighth point of his 14 points of transformation with a group of GE executives. That eighth point says, “drive out fear.” One of the executives totally disagreed. “Fear is a good thing,” I remember him saying. “Every employee should come to work every day afraid of the competition and afraid of being fired. Fear is a great motivator.” While it might be true that every organization should keep its eye on the competition (and changing customers' needs), fear can motivate good people to do stupid things in the name of trying to achieve their goals and objectives.

In my new book, The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, I highlight several examples of ways fear can have a devastating impact on an organization’s ability to make improvement happen. In this excerpt, an old-style manager, Frank Smith, has told his director of quality, Bill Mixer, to come up with a plan that will significantly improve their quality metric by the end of the week, or he will be fired. This account is based on a true story:

Tick… Tock… Tick… Tock…

The antique grandfather clock, located down the hall from Bill Mixer’s bedroom, seemed especially noisy this particular night.

Tick… Tock… Tick… Bong!... Bong!

2:00 a.m. Bill stared up at the ceiling as his wife slept peacefully next to him. She had no idea of Bill’s anguish as he kept replaying Frank Smith’s words from earlier that day; “If you can’t come up with a plan by the end of the week like I am asking, then you won’t need to be concerned since you will be on the street looking for a new job!” Bill’s 17-year-old daughter had applied to and had been accepted by several expensive universities. His son was three years younger and had already started talking about wanting to go to college as well. “How are we going to pay for their education if I am out of a job?” thought Bill. “It will be impossible to cover their costs and have anything left for retirement. I have got to come up with a plan to make our quality metrics improve from 84% to 98% and meet my boss’s expectations.”

Tick… Tock… Tick… Tock…

“If I had a couple of years and an unlimited budget, then maybe it would be possible to buy our way to better quality. But that isn’t going to happen… at least not under Frank’s watch. What to do? What to do?” Bill felt a bead of sweat roll down his forehead as the stress of the moment began to take a toll. “Hmmm…. Maybe we could start hiding parts that have defects. We could put them into the trash dumpsters and never record the errors.”

Bill’s conscience began to kick in and he thought, “No. I couldn’t allow that to happen… plus our audit programs might detect the discrepancies in the data.” Bill let out a long sigh. “Maybe we could just look the other way and send the defective parts to our customers. I could eliminate most of the inspectors and only keep the ones with bad eyesight or who are bad at catching defects. We could eliminate most of the lights at the inspection stations as well. That would cause them to miss most of the errors and our quality data will improve dramatically. Of course, it will not take long for our customers to start flooding us with product returns and complaints. I might survive for a few weeks, but the long-term prospects would look pretty bleak. No. Not the answer. What to do? What to do?”

Tick… Tock… Tick…

“I’ve got it!” thought Bill with such enthusiasm that he almost woke up his wife. “What if we just redefine what an error is and how we record our defects? If we only report the most severe problems… say the ones that might cause harm to our customers, then our numbers would improve dramatically. We would easily be over the 98% goal Frank is looking for.” Bill quickly wrote his idea down on a notepad that was on the nightstand by his bed and rolled over and finally went to sleep.

Later that week, at their staff meeting, Frank Smith asked his director of quality to present his plan to meet the new goal.

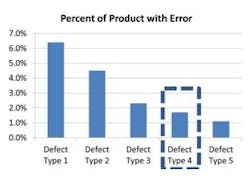

Chart of Defects

“I believe we have been too hard on ourselves,” began Bill as he avoided eye contact with his peers on the staff. He could already feel them judging him. “We are counting all of our mistakes and the quality metrics we send to our corporate offices incorporates all of this data. While the bulk of these defect types are important to track internally, the corporate executives and the outside world really only care about those problems that might cause liabilities with our customers. If you look at the chart on the screen, defect type 4 is the only one that could possibly hurt or, in rare cases, kill one of our customers. I propose that we recalculate our quality data and only include defect type 4. This would result in a quality metric of 98.3%.”

Frank stared at Bill and did not speak right away. The rest of the staff looked at Bill with a mixture of expressions that ranged from disbelief to outright horror. The silence was broken when finally, a single pair of hands began to clap…. slowly at first and then picking up speed. When the rest of the staff realized that it was Frank who was clapping, they too began to clap. “That is what I call ‘out of the box’ thinking!” said Frank enthusiastically. “Bill clearly understands what it takes to achieve excellence. I hope the rest of you can learn from Bill’s approach to meeting our goals and objectives.”

“Doesn’t this break some sort of ethics rules?” asked the director of finance.

Frank’s patience was clearly starting to be tested. “Look. One of the things I remember learning from a previous boss of mine, who was also a great mentor, is that managers, who do well in their career, are those who are good at spinning the numbers. There are many examples throughout history of executives who were able to get huge promotions and bonuses just before the business they were running went belly up. They understood the importance of telling a good story even if it means sweeping some of the problems under the rug. I hope the rest of you follow Bill’s lead and come up with creative ways to show the world how excellent we are!”

From: The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, Reprinted with permission from Productivity Press, © 2019 John Dyer

I have personally witnessed the implementation of each of the ideas Mixer thought of when trying to think of ways to change the quality metric. This does nothing to improve anything and will actually make things significantly worse. So, why do employees feel compelled to act in such stupid ways? Fear. To better understand how this works, it might help to explore four different types of fear.

Fear Type 1 – Fear of Sharing Bad News “Don’t shoot the messenger” is a common saying born from this fear type. If the boss reacts in a negative, threatening way whenever someone shares bad news, then problems will be hidden, and the opportunity to fix these issues and improve greatly diminishes. I had a boss who would tell his staff that it was OK to bring bad news to him as long as we also brought a solution. This created a new concern… people did not have the time or resources (or want the responsibility) to come up with solutions. It became much easier to just continue to hide the problems.

Fear Type 2 – Fear of Failure This is the most common type of fear. Just like Lucy and Ethel on the chocolate wrapping line, employees feel that if they miss a goal or an objective, they will be fired. This can cause stupid things to happen. For example, one operation was being challenged to achieve a specific “on time to promise” delivery metric (by the way, “on time to the customer request is a much more powerful and relevant metric). The managers of this operation would issue a promise ship date when the customer sent them the order. The staff was put under a great deal of pressure to improve this metric by the company executives. They rationalized that they should not be penalized if suppliers were late shipping in the materials needed, so they updated the promise date once all of the parts were received. This improved the on-time metric a certain amount. Later, they rationalized that they should not be punished if volume kept the order from being scheduled in a timely manner, so they updated the promise date a second time. They also felt that they should not be held accountable for absenteeism and bad luck with machine failures and quality issues, so they updated the promise date a third and fourth time. The shipping process could also cause some delays so they updated the promise date a final time just a day before the product shipped. They were relieved that they had met the challenge (without a single one of them being fired) and yet, nothing actually improved. The executives of this company thought everything was great, yet the company was losing customers at an alarming rate.

Fear Type 3 – Fear of Change We are creatures of habit and the belief is that employees do not want to get out of their comfort zone. It requires a great deal of practice to change a habit. If the organization’s leaders do not include the necessary tools and time in order to prepare people in their change process, employees will naturally rebel and the improvements will be short lived. This can be addressed by including the employees in the improvement efforts (buy-in to the changes), by setting up practice areas or running pilot runs with the change (become familiar through repetition), and document the new process and provide training aids (such as the use of operational method sheets).

Fear Type 4 – Fear of Offering an Improvement Idea Most employees will be reluctant to share improvement ideas at the beginning of a lean initiative. This is especially true if there is a fear that an improvement will result in layoffs. No employee wants to see their teammates or friends – or even themselves -- lose their jobs. So, if it is not crystal clear that no one will be removed from the payrolls due to an improvement project, then don’t expect many employees to participate. Also, if an improvement suggestion does not go as planned and the person who offered the idea gets blamed (real or perceived), this will teach others to not speak up. This fear type will continue to grow, and improvement efforts grind to a halt.

What can be done to address these fears? First, the culture of the organization will need to be examined and changed by hiring and promoting leaders who support collaboration in order to drive out as much fear as possible (defining a new normal of leadership). Second, every employee will need to be trained on what lean and Six Sigma are about in order to reduce the fear through education. Third, an improvement process based on Plan, Do, Check (or Study), Act will need to be adopted.

Embracing the Plan, Do, Check (or Study), Act (the Deming Cycle) methodology is a brilliant way to address many of these fears. It allows a team time to plan a change (which includes risk assessments), try the change in a small way, collect and study the data on what happened, and then either put the change into place or accept that failure has occurred and move back to the plan step in order to try a different approach. This teaches employees to try new things, accept change, celebrate both successes and failures, and learn along the way how to critically think and solve problems. Knowledge of this type goes a long way toward reducing fear and allowing good people to focus on doing great things.

John Dyer is an author and President of the JD&A – Process Innovation Company and has 33 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Technological University as well as an international Master of Business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France. He can be reached at (704) 658-0049 and [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.