A New Go-to-Market Model for the Industrial Internet

The collection of technologies known as the Internet of Things has created a stalemate at too many manufacturing companies. While 95% of industry executives in a recent Economist Intelligence Unit survey said they expect to be using IoT solutions within three years, 56% admit that they are not yet taking action.

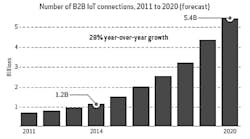

No one doubts the potential reach of the technology: By 2020, 5.4 billion objects and pieces of equipment will be making business-to-business connections on the Internet, says ABI Research, with annual growth averaging 28%. But making those connections is just the start. What companies learn once their equipment is connected is that it opens up a portal to a new way of doing business for which they might be wholly unprepared.

Thinking Outside the Machine

We believe that the only way to break the logjam is to shift your perspective in specific ways as you develop your go-to-market strategy. All of these shifts in perspective have one overriding thing in common: they are less about the technology and more about the unexpected implications arising from software, data analytics, and marketing.

Caterpillar (IW 500/23) found that out within just a few months of launching its Cat Connect capability in 2014. Suddenly, its gear in the field was generating “a quintillion bytes of incoming data.” The possibilities seemed endless: usage time and fuel efficiency could be maximized, idle time could be minimized; on-board cameras could detect obstacles that could cause mishaps and accidents.

All this data presented the potential to sell on the basis of improving productivity, profits, safety and environmental efficiency for those who run construction and mining operations. The benefits it could promise to the customer were clear. As a result, CEO Douglas Oberhelman declared at its annual shareholders meeting that the company must think “beyond the yellow iron.”

Yet the data deluge was so overwhelming that Caterpillar experienced unexpected barriers that leaders across many different industries must also overcome. As a manufacturing-based company, Caterpillar simply didn’t have the internal talent in software, data analytics, and business model innovation to scale its new ambitions in an effective way.

Learning from the early challenges faced by Caterpillar, Siemens, Bosch, Kennametal and other industrial companies, we have devised a model for thinking through how companies can approach the market by adopting five new perspectives for spotting, delivering and capturing value.

Perspective shift #1: From generating value by making different kinds of machines to generating value by analyzing different types of data.

This shift happened rather abruptly at Caterpillar, where for 90 years innovation was all about improving its iconic yellow construction equipment in new ways. Now, innovation centers on what to do with all the information coming off of those machines.

To make up for these deficiencies, Caterpillar launched a new Analytics & Innovation division charged with developing new digital business models. Caterpillar also formed a joint venture with Chicago-based predictive analytics company Uptake to enable customers to know ahead of time when its equipment would need service—shifting to a “repair before failure” model instead of the traditional “repair after failure.”

More on IoT

Find the Latest Internet-of-Things News, Trends and Best Practices

That created a new challenge, however, not only due to the sheer volume of data, but because there are many different forms of data. On one level, Caterpillar needs to unify physical machine data, such as repair logs, with Internet-based data, such as weather along with reports coming from the human operators of the equipment. As a result, a data-driven insight involving a small repair or added lubrication could avoid larger equipment breakdowns.

But in other cases, continuous performance data could prompt Caterpillar analysts to conclude that a job site doesn’t have the right mix of equipment to get the work done most effectively. That could lead a contractor to deploy different equipment and enhance productivity, and thus profitability.

As a result, the emerging needs of customers are requiring industrial companies to look towards integrating data on many levels. This new way to spot value produces knowledge and insights based on key tasks that customers are trying to get done, which leads to our second shift.

Perspective shift #2: From segmenting markets by industry sector to looking at markets in terms of the customer circumstances and “jobs-to-be-done.”

This shift involves cutting the market in new ways—in order to collect and serve different data streams to different kinds of customers. So instead of developing products by vertical industry, such as coal mining, construction, agriculture, and forestry, the idea is to define a set of circumstances, such as sole proprietors who are just managing one excavator.

Other circumstances to define segments could include the harshness of the environment, or how isolated the job site is. We call needs such as uptime and avoiding repair costs “jobs-to-be-done,” because they are the real reasons that customers “hire” the products, not for the features.

Craig Brabec, Caterpillar’s enterprise champion of data analytics, says that smart, connected products enable “micro-segmentation” of its customer base. For instance, consider road construction in the Southeast. The climate and topology requires simply different machines and applications. “We’re looking across industries, geographies and usage patterns in new ways,” Brabec says.

The same is true for global industrial giant Siemens (IW 1000/41), where the industrial internet means that different “jobs” serve as a different way to see the world. Instead of looking at sectors such as energy, transportation, and manufacturing, for instance, the $81 billion enterprise can see common circumstances across these sectors such as a concern with uptime and reliability.

For instance, Siemens created a Digital Enterprise Software Suite that connects smart objects to help predict when any given component in a micro-segment will fail. When a certain threshold of failure is triggered for any given component, a 3-D printer will generate a replacement part on location. Siemens claims it can thus deliver reliability levels of 99.9%.

This kind of capability yields insights for new kinds of IoT services and platforms, which leads to issues of how that best can be accomplished. To successfully deliver an offering to capture that identified value, companies are being forced to increase the pace of deploying key capabilities.

Perspective shift #3: From building a manufacturing-based organization known for reliability to building a data analytics organization known for speed and agility.

At German engineering giant Bosch, CEO Volkmar Denner says that IoT means that his company cannot afford to wait for innovators like Google to muscle into its spaces. “It’s not a catch up game,” Denner told the Wall Street Journal. “It’s a new game.”

With this mantra, he led the launch in 2013 of the Bosch Connected Devices and Solutions unit—to seize on what the $55 billion company calls “the culture of connected industry” by being agile enough to “keep up with the accelerating pace of change.”

Agility is even more urgent in an open world in which rival equipment can share common platforms. To speed things up, Bosch is acquiring ProSyst Software, a Cologne-based maker of software for smart devices. Its 110 employees are joining the 3,000 software engineers that Bosch now has dedicated to IoT solutions, with plans to add thousands more to work on upgrading physical objects and managing factories more responsively.

This imperative is also voiced by Caterpillar CEO Oberhelman, who marveled at how different its business was now becoming: “While it takes three to five years to design and build a new bulldozer,” he said, in the world of data analytics, “new product development is measured in days and weeks.” So much so, says Brabec, that if Caterpillar fails to keep up with the faster cycles, “we will be disrupted by companies moving faster than us.”

After all, if a startup or rival begins experimenting with new business models or product offerings first, the opportunity could be gone, which is why we urge industrial companies to pursue what we call “fast footholds.”

Fast-footholds are marketplace experiments that can lead to new kinds of positions in the ecosystem—and ultimately are about owning the new customer relationship. In the world of the industrial internet, for instance, control of the customer relationship can shift to players that redefine themselves as “application integrators.” This has to do with the mindshare of the customer being closely tied to an application that provides the customer with a critical new view of their business.

Perspective shift #4: A shift in development philosophy, from a few ‘big bets’ to a large portfolio of solutions.

Manufacturing companies have traditionally been of the mindset that they need to build capital intensive products and systems that give the firm an enduring competitive advantage. That meant focusing on big bets. While these organizations still need to maintain their product leadership, they also need to simultaneously iterate and explore a larger portfolio of related solutions.

To that end, Caterpillar has partnered with the Data Innovation Lab at the University of Illinois to source a wider range of ideas outside its traditional business focus. “This means we are going to pilot more and more new ideas,” says Brabec. “We love small failures, and we hate catastrophic ones. We like to start small, think big, and act fast.”

The act of rapid piloting requires new processes to keep costs in check, draw in and make changes based on new learning, and prepare the organization for the inevitable glitches.

But these new capabilities in spotting and delivering new value for customers need to be accompanied by new ways of turning these novel analytic services into dependable revenue streams, as outlined in our final shift.

Perspective shift #5: A shift in pricing models, from a transactional product sale to outcome-based business models.

In the past, manufacturing firms have made the bulk of their revenue selling physical products and equipment. When they did venture into services, those tended to be priced on a fee-for-service basis, or even given away in the support of product sales. But in the new realm of smart, connected objects, new business models are emerging—most notably a shift to risk-sharing, and outcomes-based pricing.

Consider the case of Kennametal (IW 500/318). For nearly 80 years, the Latrobe, Pa., company has been a manufacturer of industrial systems such as high-performance machine tooling and mining equipment. The relationship with the customer was transactional. In recent years, the 13,000-employee company has been able to turn streams of data into a new “shared rewards” business model.

This outcomes-based approach begins by benchmarking the tooling in a factory and estimating how much upgrading to smart machinery can save a company or increase their output. Then, Kennametal shares those savings and rewards with the owner of the factory, mining operator, or vehicle fleet owner. That has resulted in a fundamentally different customer relationship, one that involves constant interaction, shared risk, and continual communication. So instead of just selling mills and drills, Kennametal is now boosting productivity.

As this case shows, carving out a leadership position in a new industrial ecosystem begins by seeing the world through the eyes of the end customer.

A company that produces a gas or steam turbine might think less about adding new features to the turbine and more about how they can now keep it running all the time, improve safety or environmental outcomes, or guarantee a certain throughput. Some customers have been willing to pay for these benefits. But switching to new business models is risky, and it takes rapid experimentation to get it right.

Leading the Digital Transformation

Taken together, these five shifts in perspective are all about getting over the fear of change with a go-to-market strategy that doesn’t try to do everything at once.

In this environment, one powerful example can move markets. “When people see the data in an actionable format, it creates pull for change,” says Brabec. “A lot of the traditional barriers and the ‘who moved my cheese’ mindset evaporates, and people move forward.” The downside, in turn, can be treacherous. If you are too late to the game, you will be integrated into someone else’s system. “We need to experiment,” Brabec adds, “and not be afraid of disrupting ourselves.”

By adapting faster, an industrial company can put itself in a better position to aggregate data from other equipment suppliers and eventually own the customer relationship in a more enduring way.

As a result of shifting their perspective on how to spot, deliver, and capture value in the evolving IoT and digital landscape, some companies are choosing to create business models that define a new industrial ecosystem, while others will end up pursuing rear-guard measures. In a world where every physical object is a node on the network, the time to challenge the basic notion of what it means to create value is now.

Joe Sinfield is senior partner with the growth strategy firm Innosight. Ned Calder is a partner with Innosight, and Ben Geheb is an associate at Innosight.