How Toyota and Other Lean Cultures Are Leading With AI

On June 27, Ford’s CEO Jim Farley became the latest in a succession of prominent executives warning of large-scale job cuts consequent to AI deployment. “Artificial intelligence is going to replace literally half of all white-collar workers in the U.S.,” Farley said.

Such claims can be pretty convincing—and unsettling. Farley’s forecast of AI dominance, however, is more aggressive than most, and is not reflected in Ford’s current workforce plans. Furthermore, large-scale AI-related workforce reductions to date are almost exclusively limited to companies like Meta and Google that are closely aligned with AI platforms.

That said, it’s undeniable that tools like ChatGPT are already having a profound influence on the future of work, as anybody who’s used it to summarize a meeting, write a report, or research a complex topic can attest, and the bar keeps raising as AI platform providers release new and more powerful versions.

The big question is whether mainstream companies will be willing to sink real money into AI-related functionality. ChatGPT currently has around 400 million users, but nearly 98% of those use only the free version. And in the meantime, the major AI platforms continue to lose billions.

What OpenAI, Google, Anthropic and others are banking on is that corporate leaders, sensing the inevitably of artificial general intelligence (AGI) that can outperform most human workers, will pivot to an “AI-first” strategic orientation, a concept introduced by Google CEO Sundar Pichai in 2017.

AI-first companies, according to the vision, re-orient their core decision-making and operational processes to fully leverage the strengths of AI, adopting what you might call an AI-friendly business model. Accordingly, whenever a company seeks a new capability, “can AI do this?” becomes the default question.

AI-first companies will presumably be willing to shell out tens of thousands annually for AI “agents” that take the place of human workers. A popular target is workflows that are standard across many companies, such as handling employee queries to accounting or HR. Several vendors, for example, are offering AI-powered voice platforms that use the company’s HR knowledge base to field what are classified as routine calls to HR.

Such work, however, is not as straightforward as it may seem. According to Gina Benedict, an HR consultant familiar with these products, a satisfactory response requires “navigating feelings and emotions which you don’t expect to happen in the workplace, and which shouldn’t come up at work, but do. This is something AI has been unable to replicate, and that’s exactly why efforts to implement AI tools in this area have been unsuccessful.”

This limitation is not the exception but the rule, according to research by MIT economist and Nobel Laureate Daron Acemoglu, whose 2024 paper The Simple Macroeconomics of AI predicts that over the next 10 years, only 5% of all tasks currently undertaken by humans will be profitably automated.

In an interview with Sloan Management Review editor Kaushik Viswanath, Acemoglu argued that tacit knowledge is essential to every workplace. “Every single occupation has so many complex tacit knowledge parts and requires a lot of checking and different types of intelligence being applied to it,” he said.

Acemoglu calls for a more human-centric approach. “We are not developing AI in the best possible way,” Acemoglu explained. “That best possible way is a much more pro-human approach to AI that’s much more targeted at working with human decision-makers. It requires a bigger celebration of the places where AI is better than humans, and the places where humans are better than AI.”

Toyota’s “Simplify First” Strategy

Acemoglu’s findings are consistent with what lean leaders have been saying for decades. Uniquely human capabilities are essential to continuous improvement and central to lean’s most important pillar—respect for people.

Toyota’s approach to technology, accordingly, has been to never put technology first, but to articulate the need to improve the process and then, before evaluating automation solutions, investigate ways of meeting that need by simplifying the process (e.g., removing unnecessary steps). Taking this step avoids the common mistake of automating waste and leads to more effective and durable technology solutions.

“A lot of companies that I see that are doing concentrated learning on how to use AI are driving that out of continuous improvement teamwork,” says Jamie Flinchbaugh, founder at consulting firm JFlinch and author of People Solve Problems (and a longtime IndustryWeek contributor). “This is because they recognize that adopting a transformative technology is all about experimentation and learning, and thinking about how work is done. That’s the way we should think about how AI comes into our workplace.”

A key point here is that continuous improvement is a holistic undertaking that seeks to reduce costs and increase value. This is starkly opposed to the common preoccupation with cost cutting, and the consequent use of AI as primarily a vehicle for reducing headcount.

In the case of the HR call-answering bot, for example, a company could look at why those calls are occurring in in the first place. Are there dysfunctional aspects of the company’s management approach that are preventing people from talking directly with their managers? Is the HR handbook, which is available to everybody online, difficult to understand, out of date or full of contradictions? Is there an atmosphere of fear in the workplace? Human callers could take part in tracking down root causes that could alleviate not just HR call volumes, but other organizational problems.

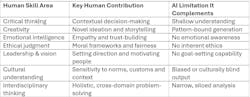

Questions like this are, for the most part, out of range for AI. I recently asked ChatGPT 4.0, “What are the most important areas where unique human skills are required to complement AI capabilities?” ChatGPT summarized its surprisingly candid response (surprising because it contradicts much of the prevailing AI hype) in the following table:

If a human had the limitations in the right column, you wouldn’t entrust them to handle a call from a distressed employee or provide guidance on how to improve the workplace environment.

The human skill areas in the left column, however, are not widely recognized or developed in most organizations, and a culture that supports them takes years to build. Lean organizations, accordingly, place considerable emphasis on developing and nurturing skills such as listening, collaborating, problem solving, following a vision and mentoring.

The Shingo Institute, which promotes operational excellence through principles established by the noted thought leader Shigeo Shingo, follows the progress of companies that have enjoyed sustained success in continuous improvement. People skills, they have consistently found, are foundational.

“One of the things we've seen consistently is the companies that have been able to sustain over time and get better and better have the engagement of the vast majority of their people,” says Ken Snyder, the Institute’s executive director. “They also have a clear purpose that the people understand and are emotionally tied to and committed to.”

Shared purpose guides these companies in how they select and deploy technology.

“We find that organizations that have a clear purpose and engagement of the people figure out how to utilize technology much more quickly and effectively than other organizations,” says Snyder. “And by effectively, what I mean is they have a clear purpose in mind. They research good means in a problem-solving kind of way. They then invest appropriately in the technology. Instead of just buying any technology that's out there for the sake of testing whether it fits or doesn't fit, they invest purposefully.”

The numbers in such companies work out far better than they do in traditional companies. “We tend to see what I call the 4X factor,” says Snyder. “Essentially, companies that achieve the Shingo criteria for getting better and better get double the productivity from technology than other companies but only spend half the amount.”

Individual workers in every sector are experiencing significant productivity improvements as they explore ways to use AI to streamline their work. But sustained results at the organizational level, such as we see in the companies the Shingo Institute has studied, cannot be achieved if AI is narrowly used as a cost-cutting tool.

”The evidence, as far as I read, is quite clear—no business has become the jewel of their industry by just cost cutting,” says Acemoglu.

Parts of this article were excerpted from Productivity Reimagined by Jacob Stoller, which was published by Wiley in October 2024.

About the Author

Jacob Stoller

Journalist, Author, Consultant

Jacob Stoller is a journalist, speaker, facilitator, and Shingo-Prize-winning author of The Lean CEO. His latest book is Productivity Reimagined (Wiley:2024).