I just finished re-reading Daniel Bell's 1973 book "The Coming Of The Post-Industrial Society,” which predicted that America would transition from a manufacturing-based economy to a service economy.

Bell was absolutely correct: America is now a post-industrial society. In 2018, approximately 80% of all jobs in the U.S. economy were in service industries, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Bell's prediction was prophetic, but he never said whether the transition would be good or bad for working people.

Many economists believe that America will flourish in the postindustrial economy.

For instance, Lawrence Summers, who was chairman of the National Economic Council under President Obama, said, “there is no going back to the past where manufacturing was the dominant sector in the economy.” He also said the new service economy would be built on “healthcare, retail, recreation, education, haircuts, insurance policies, hotels and homes.”

In a 2016 article, economics journalist Ben Casselman said that Americans are nostalgic for manufacturing jobs, but they should stop asking for them, because they are not coming back. Citing a study that found that one-third of manufacturers are on public assistance, he commented that it’s time to start asking candidates how they plan to create well-paying jobs in the service industry.

Today, unemployment is at a 50 year low at 3.7%, the stock market is booming, GDP growth has averaged 2.3% since the great recession; and America has been in the longest period of economic expansion ever (10 years). So it appears that everyone is doing okay in our postindustrial service economy. Or, so it seems.

But something is wrong!

If you dig deeper into the economic indicators, you will find that something is really fundamentally wrong with our service economy. Despite the good signs, there are large numbers of people who are suffering from years of declining or stagnant wages. Many young people cannot buy a house, go to college, buy healthcare, have children, or do as well as their parents. The Economic Policy Institute says that inequality in United States is the highest of any Western country. They say that from 1979 to 2016, wages of the top 1% grew nearly 150%; whereas the wages of the bottom 90% combined grew just 21.3%.

One of the big problems of the service economy is the quality of jobs. Every month the government announces the quantity of jobs produced but never say anything about the quality of new jobs. But, if you go to the Bureau of Labor Statistics website and look at Occupations with the Most Job Growth, you will see a 10-year projection of jobs to 2028, which is 47 million of the fastest-growing jobs. If you remove the 15 million professional jobs that require a college education or advanced training, you will find that 32 million jobs (68%) have an average wage of $31,561 per year. This is important because 66% of the America's 163 million workers have a high school education or less. The post-industrial service economy is simply not producing enough living wage jobs for workers without college educations.

According to a recent Brookings Institution survey, 53 million Americans are earning low wage, and their median Wage is $10.22 an hour, or $17,950 per year (33% of the workforce).

The rise of finance and debt

The rise of the service economy also paralleled a steep rise in debt. Beginning around 1980, workers began using credit cards as a way to continue consumption, and students began borrowing to go to college. According to Forbes, student debt was $1.47 trillion at the end of 2018—and since 1980, credit card debt has risen to $1 trillion per year.

The country went from making money producing goods to making money from paper. As regulation was virtually suspended, the financial industry was allowed to innovate and create all kinds of financial engineering tools. Those same people who gave us junk bonds and leveraged buyouts now give us credit default swaps, derivatives, structured investment vehicles, mortgage securitization, and many more.

In the last four decades, as America transitioned to the postindustrial service economy, there was an explosion of debt by the financial sector of the service economy. The explosion is documented in terms of the growth of private debt, which is defined as household, financial, and nonfinancial corporate debt. According to Kevin Phillips’ book “Bad Money,” total private debt rose from $1.8 trillion in 1974 to $36 trillion in 2006. As of 2018, the federal deficit was $22.03 trillion and the accumulated trade deficit was $12.2 trillion. Debt is now the lifeblood of the financial sector, and America is the largest debtor nation in the world.

President Bill Clinton's treasury secretary, Robert Rubin, said, finance is leading the nation into a new postindustrial era with services, especially the lucrative financial ones, replacing manufacturing, “just as the latter had ushered out the agricultural sector.”

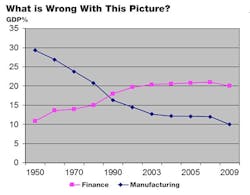

The following chart below shows that Rubin was right, and finance has replaced manufacturing as the dominant economic sector. Based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the chart shows that from 1950 to 2005, manufacturing declined from 29.3% GDP to 12%, while finance grew from 10.9% to 20.4% of the economy.

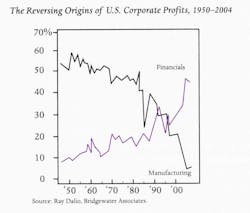

The second chart shows that manufacturing's share of US corporate profits was close to 60% in 1950, but declined to 5% by 2004. During this same period the finance sector grew from 9% to more than 40% of all corporate profits.

The post-industrial service economy was a transition from manufacturing to a finance economy based on debt, which has resulted in growing inequality and wage stagnation. So, the big question is, will the continued decline of manufacturing and the growth of finance result in a better future growth for everyone? The lesson from history says no.

History reveals that the replacement of manufacturing by finance has happened many times. In the 16th century, Spain dominated half of Western Europe and almost all of South America. They had a huge army, and the biggest fleet in the world. They brought back ship loads of gold and silver from the conquered countries. Spain lost interest in their agricultural and manufacturing sectors and began to focus on money and finance. After the 30-Year War ended in 1648, Spain's glory days were over and they began to decline as a leading power.

After Spain, the Netherlands became the leading economic power. The Dutch had a huge fleet and their merchants had outposts from Japan and South Africa to India and Brazil. But they also began to focus on finance and debt, and from 1688 to 1713 fought a series of wars that depleted the nation and quintupled their debt. The Dutch government did not pursue reform and did not curb financialization and by the 1750s were in decline.

By the 1780s, Britain was on the ascent as a power and dominated the world during the Victorian 19th century. The leader in the Industrial Revolution and in manufacturing for more than a century, Britain had the world's greatest Navy, and colonies stretching from India to Africa to Australia. Britain followed the Dutch model, and set up a stock exchange and a central bank. Many of the financiers in Europe then moved to England, anticipating the rise of British banking and financialization. Eventually, manufacturing became secondary and banking became the dominant sector of the economy. Fighting in the two world wars decimated Britain, and by 1949, they began their decline as an economic powerhouse.

Phillips makes the case that "no previous leading world economic power has enjoyed a full-fledged manufacturing renaissance, after becoming unduly enamored of finance." In other words, once the country moves to financialization and away from manufacturing, it loses its economic power and begins to decline.

Relying on a postindustrial service economy based on the growth of debt is not sustainable, and we may be on the road to another financial calamity. Instead, it is important that we reverse the decline of the manufacturing economy for the following reasons:

1. R&D and American innovation.

According to the book “Rising Above the Gathering Storm,” the only way America can compete in the future is with a strategy of innovation. The book goes on to say that a variety of economic studies over the years reveals that half of the growth of the GNP in recent decades has been attributable to progress in technological innovation.

Our innovation leadership is in danger because multi-national corporations have been sending their manufacturing and technologies overseas and China has been stealing our new technologies since 2001. According to a Harvard Business Review article, this mass migration has seriously eroded the domestic capabilities needed to turn inventions into high-quality, cost-competitive products, damaging America’s ability to retain a lead in many sectors.”

If “innovation” is going to be the strategy that keeps America the number one economy, then private research and development is the key—and 68% of R&D comes from manufacturing. The important point is that the majority of innovation and new technologies come from manufacturing—not the service industries.

2. Advanced technology products.

An analysis by the Brookings Institute America's Advanced Industries defines 50 U.S. industries as advanced technology industries. 35 of the advanced industries are manufacturing industries, which make optoelectronics, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, advanced materials, self-driving cars, and weapons systems, to name just a few.

We must depend on these advanced technologies to succeed in our innovation strategy. But we are slowly losing them through outsourcing, forced technology transfer, and Chinese theft.

3. Exports. In 2018, we exported $2.5 trillion and imported $3.1 trillion, for a deficit of $623 billion. Sixty-seven percent of our exports are manufactured goods—so if we are going to have any chance of reducing the trade deficit or increasing exports, the only answer is to increase manufacturing in the U.S. Service is only 33% of our exports, so increases of service exports simply won't do it.

4. National security. An article in the New York Times by Peter Navarro makes the case that the decline of the U.S. industrial base threatens national security.

The article is based on a government-wide assessment of America’s manufacturing and military industrial base, identifying, “almost 300 vulnerabilities, ranging from dependencies on foreign manufacturers to looming labor shortages.”

Thirteen industries are declining that manufacture products and technologies critical to our defense, such as propellant chemicals, batteries, specialty metals, hard disk drives, flat panel displays, semi-conductors, printed circuit boards, machine tools and advanced materials. We can't have strong national security if we continue to outsource components and critical materials to low-cost countries.

5. Manufacturing as the foundation of global power. From the rise of England in the 19th century; to the rise of America, Japan, and Germany in the 20th century; and the rise of China, Taiwan, and Korea in the 21st century: Manufacturing has been the key to the growth and power of each country. The power is not just building factories that manufacture goods; it is making the machinery that makes the goods. In my recent article, Is US Manufacturing Losing Its Toolbox?, I showed that machine shops, machine tools, forging, stamping, semiconductors, hand tools, and many machinery industries that are the tools of production are all declining. The primary point is that to remain a global power, America must have a strong manufacturing base.

The fallacy of the postindustrial service economy was best summarized by Harold Myerson in the Washington Post. He said, “The Wall Street/Wal-Mart economy of the past several decades off-shored millions of factory jobs, which it offset by creating low-paying jobs in the service and retail sectors: extending credit to consumers so they could keep consuming despite their stagnating incomes; and fueling, until it collapsed, a boom in construction.” He also writes that, "of all the lies that the American people have been told in the past four decades, the biggest one may be this: We'll all come out ahead in the shift from an industrial to post-industrial society … The post-industrial economy turned out to be a bust. The time for neo-industrial America has arrived,”

I would add that continuing reliance on the post-industrial service economy might lead to a nation of software programmers and tattoo parlors looking for someone to invoice.

Michael Collins is the author of Saving American Manufacturing and The Manufacturers Guide.