Sometimes the waiting really is the hardest part. Anyone who has set foot in a packed bar knows the frustration of flagging down a bartender to buy a drink. Likewise, the bar staff can feel overwhelmed and lose potential customers or tips if wait times are long.

In 2008, entrepreneur Josh Springer developed a unique beer-dispensing system from his garage in Washington state to help bars increase their service levels. Springer named the company GrinOn Industries. He eventually moved GrinOn’s manufacturing operations to a 26,200-square-foot facility in Indianapolis to be closer suppliers and a larger domestic consumer base, says co-founder and COO Mike Price.

While domestic sales jumpstarted the business, a significant portion of the company’s current and future growth is coming from exports, Price says. GrinOn currently exports to 40 countries, and in some months, exports outpace domestic sales, according to Price.

Price joined Springer in 2008 to help advance the company’s growth efforts. Price and Springer quickly realized their product had global appeal because the service issues that bars and restaurants face are not unique to the U.S., Price says.

“It was pretty quick from when we had the first website up that – within a year or so – that we began to get some random international inquiries,” Price says. “A lot of times it was someone who touring in the States, and they saw our products in action.”

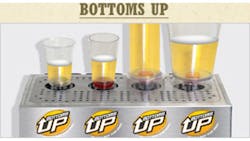

The product, called the Bottoms Up Draft Beer Dispensing System, is a hands-free method of pouring beer through an opening in the bottom of a glass, pitcher or cup. The container fits over a nozzle post on a beverage dispenser that automatically fills the cup to a pre-programmed amount so the server can take care of other customers or tasks while the glass is being filled.

GrinOn’s export business began in 2010 when one of its early customers, Anheuser-Busch In-Bev, referred GrinOn to one of its subsidiaries in Canada. Canada made sense as a first export market because the country shared a common language, and GrinOn was able to receive “nonresident importer” status.

The company’s product is now present in several foreign markets, including the European Union and Mexico. Price recently shared some of his company’s export-growth strategies and lessons learned.

Tell me a little more about what it means to be nonresident importer in Canada and the benefits.

In effect, to our customers in Canada, they get to pretend like we’re a Canadian company that they order from. They don’t have to know how to clear an international shipment. They can order like we’re next door. We, as a nonresident importer, are able to clear the shipment for ourselves to deliver the goods. In that case, we use FedEx Trade Networks to clear the shipment. That makes it easy for people without international trade experience to just order products from U.S. manufacturers that have that status, which is really straightforward to get. The only difference is an additional line item on the invoice for the required taxes that are collected. As an example, there’s a 5% general service tax for anything that crosses the border into Canada, so we charge them for that.

How do you get the nonresident importer status?

You have to fill out some paperwork, and there was some training involved just to make sure we would be compliant with all international laws because you need to keep records for international trade. We have folders on our company server where we store the commercial invoice, which is the invoice to the customer, with the classification code on it for tax purposes.

Just as a general recommendation, I would suggest researching to see if anyone has classes – such as FedEx, UPS or any of the freight companies. And the U.S. Department of Commerce offers classes, as well. What we found is that while it was pretty easy to figure out how to export to Canada, it was much harder to figure out how to export to other countries, especially where English wasn’t the first language, such as Mexico. We began exporting to Mexico in 2011.

What made you decide to enter Mexico where language is a barrier? How did you overcome that?

We found a great partner (distributor) down there who was willing to translate everything and willing to buy the goods and put up with the fact that we didn’t know everything. We had our documents translated, did a couple of videos in Spanish and gained a large customer. We have one party we want to work with in each foreign country – sometimes those people represent more than one country because of the common language. For example, German is spoken in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. So we have one partner for those three countries. They handle all of the sales, service and support in the foreign country.

Do they handle compliance or customs clearance for you? How do you manage compliance challenges or issues?

No. They handle very little of that for us. The onus is on the manufacturer – whoever is the originator; not the recipient. It works out fine for us because, for example, we prioritize the European Union as a good market for us to export to because there are a lot of English speakers and one set of regulatory standards across a number of countries. I highly recommend reaching out to the U.S. Department of Commerce because they are there as a taxpayer-paid resource to help us how to figure out how to export our U.S.-made goods to any country, provided it’s legal. And they will tell you if it is or not or help you figure out what hurdles you need to overcome. But you need to do your own research and take personal responsibility.

Overall, what has exporting meant to your business?

It’s helped us become a better manufacturer to our domestic customers, as well, and provide better service to them. It forces us to be less assuming about things. Sometimes we realize when we create materials (such YouTube demonstration videos) for our foreign market that, “Hey wait, we also don’t have that domestically, so let’s produce that in English first.”

About the Author

Jonathan Katz

Former Managing Editor

Former Managing Editor Jon Katz covered leadership and strategy, tackling subjects such as lean manufacturing leadership, strategy development and deployment, corporate culture, corporate social responsibility, and growth strategies. As well, he provided news and analysis of successful companies in the chemical and energy industries, including oil and gas, renewable and alternative.

Jon worked as an intern for IndustryWeek before serving as a reporter for The Morning Journal and then as an associate editor for Penton Media’s Supply Chain Technology News.

Jon received his bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Kent State University and is a die-hard Cleveland sports fan.