How the US Economy Lost Its Independence, and Workers Their Livelihoods

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

In 1984, John Naisbitt, in his best-selling book Megatrends, said that Third World countries would take over manufacturing, and the U.S. would happily transition to a service economy where most people would work in service jobs rather than work with their hands. His prediction was prophetic. Today there are 135 million service workers versus 13 million manufacturing workers

Many economists and academics jumped on the “post-industrial service” bandwagon and convinced themselves and most citizens that the transition is a good and inevitable thing. In 2005, The Economist published an article that summarizes the prevailing belief about manufacturing employment. The article, titled “Industrial Metamorphosis,” carried the following brief description: “Factory jobs are becoming scarce. It’s nothing to worry about. ”

So, when The Economist says there is nothing to worry about, it depends on whether you have a college degree and a good chance to claw your way into the credentialed elite. But if you are among the 56% of all workers who have a high-school diploma or less, you may be struggling to make ends meet. Millions of workers in this category feel that something is very wrong in the post-industrial economy and are despondent about their future.

Today, the stock market is near an all-time high, and unemployment is low. In fact , many jobs are going unfilled. So, what is the problem? When you look deeper into the post-industrial economy, you will find that people cannot find jobs with decent pay and benefits, and cannot afford to buy a home, afford health insurance or save for retirement. They are worried about their future and their plight doesn’t square with the service economy described in the headlines.

Contrary to the view of many economists, the smooth transition to the service economy has become a very rough road and has created many losers. Unlike Europe, in America the government does little to take care of the losers.

I will make the argument that there is growing proof that the post-industrial service economy is not going to provide the wages, living standards or the economic growth in promised by many economists. And that trade policies have led to de-industrialization, slow growth, stagnant wages, lower living standards and rising trade deficits.

A 40-Year Decline

Over the last four decades, multinational corporations decided that it was in the best interest of their shareholders to move jobs and production to low-cost foreign countries. Under the flag of the free market, the public found out that there was no loyalty to the United States. Instead of trying to protect American industries and slow down the rush to low-cost countries, the only real loyalty was to the short-term interests of their shareholders.

Since 1979, America has lost 7.5 million manufacturing jobs (36%)—and according to the Economic Policy Institute, 5 million of these jobs were lost since 2001, after China was allowed into the World Trade Organization. The reason these jobs are important is that the wages and benefits from manufacturing jobs provided membership into the middle class to families with a high school education. Lost manufacturing jobs were chiefly replaced by lower-wage service jobs.

Other effects include:

Trade Deficit: To keep the outsourcing game going, we must borrow money from our foreign competitors, but in 2021 the annual trade deficit exceeded $1 trillion. According to the Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA) the $1 trillion trade deficit was 3.2% of GDP, and caused the economy to shrink in the first quarter of 2021 by -1.4%. The overvalued dollar made exports less competitive and worsened income inequality.

The argument by most economists is that importing cheap goods allows citizens to enjoy the benefits without paying for them. But as CPA says, “No nation has ever gotten rich or increased its standard of living over time by borrowing to finance current consumption. At some point in the future, the bill always comes due, and at the end of 2021 the U.S. owed a net $18.1 trillion to the rest of the world” The irony is that we can only pay this back by running a surplus, which means increasing exports. But 70% of our exports are manufactured goods, so to have any chance of paying back our debt requires growing manufacturing and exports. Sadly, there is no government program to address the export problem

Shortages: With the COVID-19 pandemic, America woke up to the fact that we had outsourced our PPE and critical medicines. Most citizens didn’t know that we now totally depend on countries like China and India to supply most of our drugs and pharmaceuticals. We are dependent on China for 90% of our antibiotics and half of our generic medicines. Shortages also include drugs such as morphine, dopamine, lidocaine and even the contrast dye used to install stents in blocked arteries.

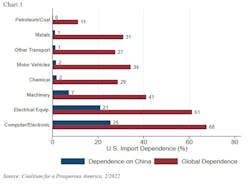

The chart above shows the dependence we have on China and other foreign countries for our critical industries. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s tensions with Taiwan, one wonders how we ever allowed ourselves to get into such a vulnerable position, one where we have lost control of so many industries and technologies.

The Industrial Commons: Besides losing our technology and inventions to our competitors, we are losing skilled workers and the know-how, suppliers and capital investment that comes with investing into production at scale. Gary Pisano and Willy Shih, in their book Producing Prosperity, make the argument that “investing in the industrial commons is not a matter of patriotism; it’s is a matter of good business leadership.

Innovation: Everyone agrees that America can only compete globally with a strategy of innovation. But with a shrinking manufacturing sector, it begs the obvious question, “How can we do this if we continue to lose the industrial commons?” More importantly, the key to both innovation and new technology is research and development, and 70% of all R&D comes from manufacturing, not service.

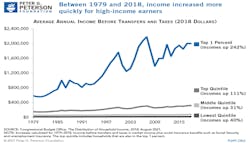

Inequality & The Shift of Wealth: Chart 2 shows the great shift in wealth started in the 1970s and has been a big factor in the decline of the middle class and the rise of serious economic inequality. The gaps between the haves and have-nots have accelerated. If you are part of the 1%, life is good, and you’re probably interested in supporting legislation that maintains your position. But if you are in the middle or lower class—or if you are one of the 83 million workers who do not have a college education—then the future probably looks bleak, which has led to general unrest in working America.

Will the Service Economy Create Enough Good Jobs?

The real issue that the economists never seem to address is this: What kind of jobs will be created in a post-industrial economy? Will there be enough family wage jobs to allow all members of the middle class to raise families? Will the new jobs pay enough to maintain middle-class living standards?

The Job Quality Index – A new economic indicator called the U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (JQI), shows that the economy has produced a lot of jobs, but they are increasingly “low-quality” service jobs. Chart 3 below shows that the quality of new jobs has been decreasing for 30 years. In 2020, the JQI was approximately 81, which means that there were 81 high-quality jobs for every 100 low-quality jobs. This is a significant reduction of good jobs since 1990.

The Weakening Trend

The fact that the U.S. economy has shifted, creating more bad jobs than good jobs, does not bode well for those workers in the middle class with a high-school diploma or less. Someone with a high-school diploma who loses a manufacturing job will likely find a job in one of the following industries, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Leisure and hospitality, which has 14.7 million non- management employees earning an average $16.58 an hour and working an average of 25.8 hours per week.

- Administration and support, which has 8.1 million jobs earning an average of $22.36 per hour and working 34 hours a week.

- Retail, with 13.2 million jobs earning an average of $18.83 per hour and working 31 hours a week.

- Warehousing and transportation, with 5.2 million jobs earning an average of $24.64 per hour and working 38 hours a week.

Twenty dollars per hour is only $38,400 per year, so if you are one of the 41 million people who must work in these service industries, attaining the American Dream may be problematic.

It is my contention the post-industrial service economy—especially one that that will sustain current living standards—is a myth. Having any chance of reducing inequality, creating good jobs, reducing critical shortages and competing with an innovation strategy will require reducing the trade deficit, rebuilding the industrial commons and increasing exports – which means reshoring the manufacturing industries and technologies now in foreign countries.

These problems were mostly caused by America’s multinational corporations, but in 2019 the group of major corporations that comprise the Business Roundtable issued a statement saying they now want to lead their companies not just for the benefit of their investors, but “for the benefit of all stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, and communities.” So, it is time for them to walk their talk and take a longer-term view of what is good for them and the country

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.