EV Affordability Is a Problem that Won’t Magically Go Away on the EPA’s Timeline

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

ANALYSIS

The EPA’s proposed vehicle emission standards are great for the environment and just what some manufacturers wished for. Yet increasing CO2 vehicle emission standards will ultimately reduce overall demand for light vehicles by 2030. Here comes the regulatory pain.

The vehicle product strategy of General Motors, and to a lesser extent Ford and Stellantis, is very clear. They are on a path to be all-electric by 2035. Incentives? Yes, bring them on, and let the free market do the rest. The Biden administration listened, partially.

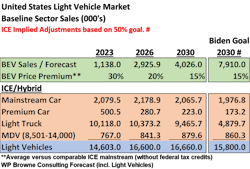

The Biden administration has done a decent job of providing taxpayer-based incentives to manufacturers and consumers that will increase BEV sales in the United States. The Inflation Reduction Act’s “carrots” are expected to lift U.S. battery-electric sales to 4.03 million units by the end of the decade, or 24.2% of the light-vehicle market. This outlook is far below the 50% vision pitched by the White House. The reasoning is straightforward: BEV (lack of) affordability and purchase alternatives.

Price parity with gasoline versions will be difficult to achieve even with battery costs of $100 kWh (vs. $150 today). At the lower battery-cost level, the price of battery-electric vehicles will still average 20% above comparable gasoline models through 2026 (without credits). Why? Because shareholders want profits. The affordability problem is obvious.

Consumers will also have a wide choice of hybrids from Ford, Stellantis and Asian brands that eliminate any public charging or recharging-time anxiety—at a lower price.

Additionally, while the demand for passenger cars has declined significantly, the need to provide affordable transportation to lower-income consumers will still be a core part of the market. This income group may not do the cost-of-ownership calculations that economists love and, more concerned with monthly payments, could overextend themselves.

The incentives in the IRA allowed consumers time to gauge acceptance of electric vehicles and see whether extensive public charging station deployment will really come to pass. It also allowed manufacturers time to adjust the mix of product offerings to consumers. Our baseline forecast assumes that ICE and hybrid vehicle deletions will be limited. By 2026, OEM offerings would essentially mirror what exists today. Customer choice will be extensive. The market will determine the level of progress.

Is a 50% BEV mix achievable? Yes, with more time. Unfortunately, this was not good enough for the EPA.

Going Beyond the Vision

The recently proposed modifications to greenhouse gas emission standards for the period 2027-2032 (CO2 and others) will significantly improve air quality. There are a host of independent studies, and real world examples, that make the potential improvements undeniable. Also undeniable: the standards will alter the market-based trajectory of battery-electric sales—and overall industry demand.

The regulatory changes reduce the average level of CO2 permitted to 82 grams/mile—based on a footprint / sales weighted basis. The 2032 standard is 65% lower than 2021 levels.

The business end of the EPA’s proposal seems problematic. It is too early in the proposal-discussion process to make a detailed light-vehicle forecast. Some of the conclusions seem too obvious, and certainly need to be debated.

If the EPA is expecting a BEV sales share of 67% by 2032, then MSRP parity with ICE vehicles is mandatory, and price reductions will need to be accelerated. BEV premiums today average 30% when compared to an equivalent ICE vehicle.

Fortunately, everybody in the business is starting to recognize the premium overreach. Jim Farley, Ford CEO, recently indicated that electric vehicle prices would probably fall by 5% this year and next. That’s great news for mainstream SUV and pickup buyers considering going electric (but bad for profits).

Without BEV-ICE price-parity, industry demand will be reduced by 800,000 units by the end of the decade. Stated differently, that’s three-plants-worth of volume. It would take a $60/kWh battery cost and full tax credits on every vehicle to maintain industry demand and manufacturer profitability.

Portfolio disruption will be severe. The serious tear-up will start in 2026 when program changes face scrutiny beyond requirements to achieve the 50% vision. Decisions surrounding gasoline product programs—e.g., carry over for a few more years, drop or improve—could be taken away from the CEO in favor of a bureaucrat. Forget navigating penalties and buying credits, an automaker’s board of directors needs to be able to ask, “what do consumers want?”

The highest level of disruption will be borne by mainstream SUV and half-ton pickup buyers, customers that generate serious profits for OEMs. These customers will need to be convinced that the switch is the right value proposition. Prior to the proposed standards, the switch would have been market-driven—it was a goal. Now, the proposed standards will require company incentives on top of federal tax credits to ensure the switch.

Premium brands will be immune from the pricing quagmire. Their customers will just determine which brand gives them personal panache. The fact that some premium brands will be all-electric by 2030 will not be a demand problem. It will be a potential image problem. If a premium brand didn’t capture the customer’s ego with ICE versions, then BEVs won’t help. Everybody will have them.

There are also two mainstream sectors that are expected to maintain stability through the balance of the decade: Passenger cars and medium-duty vehicles (pickups and vans above 8,500 GVWR). Passenger cars deliver affordable transportation to consumers in the United States, Canada and Mexico. Unfortunately, the Detroit 3 have thrown in the towel and handed the sector to Asian brands. MDVs are work trucks plain and simple and have higher emission standards than light trucks. Ford, GM and Stellantis dominate this sector and are unlikely to push consumers into BEVs.

Electric vehicle sales reaching 67% by 2032 is a moon shot. The timing is too fast given the required product decisions in 2027. Serious uncertainty will remain across a range of issues during that time. Let’s get real: vehicle manufacturers, suppliers and dealers need to make money; it’s fundamental.

Let’s hope those BEV cost-reduction programs really materialize, that BEV models are reasonably priced above comparable ICE models and that consumers have enough income to sustain overall demand. CFOs know the answers to those questions. Yet, their analysis may not have been passed over to the PR department.

Let the comments and debate begin.

Warren Browne is president of RFQ Insights and is adjunct professor of economics and trade at Lawrence Technological University. Browne retired from General Motors in 2009 after 39 years of service. From 1991 to 2009, he held senior executive positions at GM.