Labor Days: Meeting Our Workforce Challenges!

There is the truth about the U.S. workforce. And then there is a deeper -- and troubling -- truth.

The truth, according to the U.S. Labor Department, is that the nation created about 5.3 million net new jobs between August 2003 and May of this year, more than all the jobs Europe and Japan together created during the same period. Overall U.S. unemployment remains relatively low at 4.8%. This year's college graduates found themselves in the most positive job market in five years.

The deeper and troubling truth is that much of U.S. manufacturing is faring far less well. U.S. manufacturing has lost nearly 3 million jobs since January 2001. Many are gone for good. What's more, such emerging manufacturing sectors as biotechnology and nanotechnology -- along with such established and restructured manufacturing sectors as aerospace, autos, steel and textiles -- require fewer production people than did the dominant industries of the past. Some domestic jobs -- estimates range from a few hundred thousand to the low millions -- have moved offshore as manufacturers have sought lower-cost labor and shortened the supply chains that link them to foreign customers. Some domestic jobs have disappeared as manufacturers have dropped secondary product lines to concentrate on core businesses. Some domestic jobs have been eliminated in the wake of corporate mergers. That said, more than 14 million people, greater than the combined populations of Virginia and Massachusetts, the U.S.'s 12th and 13th most populous states, remain in the U.S. manufacturing workforce, nearly 10.2 million of them in production jobs.

| New Faces, New Expectations One Worker's Story The Workforce: Three Perspectives |

Ninety percent of manufacturers reported moderate to severe shortages of qualified skilled production employees, relates last November's American workforce study conducted by the Manufacturing Institute, the research arm of the Washington, D.C.-based National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), and Deloitte Consulting LLP. Sixty-five percent of the manufacturers surveyed reported moderate to severe shortages of scientists and engineers. And 39% reported moderate to severe shortages of qualified unskilled production employees. "This human capital performance gap threatens our nation's ability to compete in today's fast-moving and increasingly demanding global economy," the study warns.

A shortage of skilled workers remains a daily reality among manufacturers. Two-thirds (68%) of the people responding to an online IW poll earlier this year reported a severe shortage of skilled workers. Less than one-fifth -- 18% -- said the supply of skilled workers had never left them shorthanded.

"If our country is to remain competitive, the issues of education and training reform now must be given at least as much focus as top business concerns of trade, tax, energy and regulatory reform," insists the NAM/Deloitte workforce study. Yet, there has been precious little serious attention paid to worker skills in manufacturing during the 10 months since the report was released.

Will manufacturing workers without sufficient skills, as once was said of the poor, always be with us? Has more than a generation of well-intentioned training and development programs in both the private and public sectors of the world's largest economy largely failed, a failure that cannot be written off as just bad luck? Both are among the several critical questions that must be asked and answered if manufacturers are to meet today's workforce challenges, including the biggest question of all: Is there a future for America's manufacturing workforce?

"The challenges we face aren't the kind that can be ridden out," Ron Gettelfinger, president of the United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW), bluntly told the union's convention in June. "They're structural challenges, and they require new and farsighted solutions."

Stark Differences

The working world of U.S. manufacturing is starkly different in 2006 from what it was a generation ago. As a proliferation of trade agreements and dramatic growth in foreign direct investment underscore, the world is far more economically interconnected and interdependent now than then. In just the past 10 years, the market share of U.S. operations of European and Asian automakers has advanced to more than 22% from less than 15%. Today, only two manufacturers, Chicago-based Boeing Co. and Toulouse, France-based Airbus SAS, are left to battle for dominance in the world's large-commercial-aircraft skies. In only the past five years, China and India have achieved almost mythic status as multibillion-dollar markets and lower-cost manufacturing sites. Wireless technology is changing the ways companies communicate with suppliers and customers, and other technologies have helped make factories leaner and meaner centers of competition.

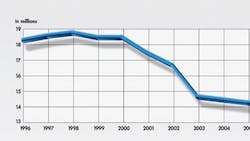

Examine the U.S. Labor Department's job numbers for each September of the past 10 years and you'll see U.S. manufacturing employment peaked at 18.7 million in September 1998. This September, manufacturing employment is 14.2 million, 4.5 million workers fewer than eight years ago.

Number of Manufacturing Workers

Some workforce problems of the past persist, however. For example, manufacturing continues to have an image problem -- although for some it seems to be less about dirt, dust and the Rust Belt than about manufacturing's future in America. Among high school and college graduates "there's a real perception . . . that manufacturing is not going to be in the States [over] the long term," says Brent Nolan, vice president and COO of Integrated Performance Systems, a Wylie, Texas-based manufacturer of printed circuit boards. Skilled workers coming into his company tend to treat it as a way station on the road to service-sector jobs. So when Nolan looks 10 to 15 years into the future, the picture "starts to get a little bit scary" because there are no younger skilled workers to replace those retiring.

Meanwhile, the picture of U.S. manufacturing jobs as dirty, low-paying, menial and even dangerous has not been erased. Add that image to post-recession layoffs, factory closings and jobs sent to places beyond U.S. borders and it's little wonder people ask: Why would anyone choose manufacturing as a career?

National and statewide campaigns are underway to lure workers into manufacturing by painting a different and more accurate picture of clean, competitive-paying, highly skilled jobs that have futures. Notable this year has been steelmaker Nucor Corp.'s advertising campaign portraying its workers as vital, involved and savvy. "Interestingly enough, we've found a way to become more competitive in the world by paying our employees more. Instead of less. It's called pay-for-performance," reads one of the ads. Still, recruiting for manufacturing isn't easy, confirms Phyllis Eisen, vice president of the NAM's Manufacturing Institute and executive director of its Center for Workforce Success. "Every industry is out there trying to get this new, young, highly skilled generation, and we have to make sure they want to come to manufacturing," she says. "We have an uphill battle because the stereotypes are so deep."

Best Practices At Best Plants

See Also... |

These plants invest in their workers and intimately involve their workers in myriad processes. For example, IW's 25 Best Plants winners and finalists in 2005 devoted as much as 6.8% of annual labor costs to training. And production employees each received as many as 170 hours of classroom and on-the-job training. At 83% of the plants, more than 50% of the production workforce participated in self-directed or empowered work teams, handling such responsibilities as training, quality assurance, daily job assignments, materials management, production scheduling, skills certification, inter-team communications, and safety reviews and compliance. A remarkable 96% of the best plants in North America crosstrain their production employees, providing the workers with the skills to do two or more jobs.

Meanwhile, at Boston Scientific Corp.'s medical device plant in Wayne, N.J., a three-year-old initiative focuses on having trained replacements for skilled employees who retire or leave. "We're a pretty small plant, and because we don't have a lot of extra people around, we really got to make sure we plan for replacement [in] our critical positions," stresses Michael F. Jordan, director of human resources at the 270-person facility that was a Top-10 IW Best Plants winner in 2005. The plant, with an aging workforce, weaves vascular grafts, an exacting task with unique technologies for which, he notes, training can't be done in anything like 30 or 60 days. "So it becomes absolutely critical to build internal apprenticeship programs and prepare folks for tomorrow," says Jordan.

Going To School At IRU

At the same time, north of New Jersey at its fabled education center in Crotonville, N.Y., General Electric Co. continues to be in the forefront of large manufacturing and technology companies seriously engaged in management development. Others include Boeing, 3M Corp., Oracle Inc. and $10.5 billion Ingersoll Rand Co. Ltd.

IRU has allowed him to establish relationships with Ingersoll Rand managers outside his business sector both within the U.S. and abroad, says Carmel, Ind.-based Derrick Marris, general manager of commercial security, a $2.2 billion business segment of Ingersoll Rand Business Security Services. "Meeting the people across sectors and globally probably would not have happened -- at least not to the extent that it did -- had I not gone to Ingersoll Rand University," he states. "I'd probably be only about 25% of where I am today." Marris, who's been with the company about three-and-one-half years and who has a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and an MBA, says IRU also allowed him to "very quickly" grasp the company's culture and how to use the tools and language that other managers use. Among the courses "that have worked really well for me" are entrepreneurial general management and interpersonal leadership, says Marris.

Help -- From The Feds?

The competitiveness debate cannot remain inside the Beltway," stresses William T. Archey, president and CEO of AeA, an association of high-tech companies. Yet from within the Washington, D.C., beltway has come a tool that the NAM believes will be of major benefit to manufacturers and educators. Three months ago the U.S. Department of Labor published a kind of checklist of skills workers needs to make it in advanced manufacturing. The skills range from demonstrating a willingness to work to possessing academic competence to having a commitment to quality assurance and continuous improvement.

"The new framework does not replace sector-specific manufacturing association skills standards, but rather provides a foundation of core skills needed across-the-board to be a high-performance worker in today's advanced manufacturing," stated John Engler, NAM's president, when the checklist was unveiled on May 22. "It will be especially valuable to small manufacturers who don't have huge human resource departments to track the rapidly changing skill requirements of advanced manufacturing that are necessary to compete in today's global marketplace."

There's likely to be knee-jerk resistance from some manufacturers to even reviewing the lengthy skills checklist, stemming in part from a belief that the federal government is never going to "help." There's reason for their cynicism. The Labor Department's heavily promoted Job Training Partnership Act of the 1980s and 1990s had, at best, mixed results. And the department's training-assistance program for workers whose jobs have disappeared as U.S. international trade has surged has been a failure, offering too little too late.

Yet, "we are in the race of our lives for talent, and the country with the best workforce is going to be the winner," stressed Eisen, the vice president of the NAM's Center for Workforce Success, which helped develop the checklist of core competencies. "This new skills framework will empower individuals, employers and educators with essential guidelines to get a great job, hire a high-performance worker or teach what's necessary for a career in advanced manufacturing."

The test will be whether in the next few years private- and public-sector efforts will pay off or whether a generation from now today's workforce challenges remain unmet.