Trump's Auto Policies Would Reduce US Production Targets

President Donald Trump’s two-pronged automotive strategy is about to seriously disrupt the North American vehicle business. Importantly, the potential policies will result in decreased U.S. vehicle production.

Automotive manufacturers and suppliers have been working in a relatively stable environment over the past four years. The future regulatory and trade environment was clear, even if manufacturers didn’t like some of the rules—like very stringent CO2 standards that were expected to boost demand for zero-emission light vehicles. To ease the pain, manufacturers, suppliers and consumers were offered incentives to make the transition to electric vehicles easier.

The Current View

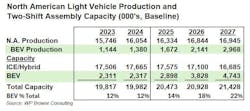

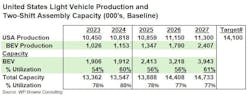

Manufacturers and suppliers responded by offering more consumer choice and an increased supply of electric vehicles. Under the current economic outlook and existing federal incentives and regulations, North American light vehicle production is expected to increase to almost 17 million units by 2027. At the same time, battery-electric vehicle production will increase to 2.97 million units. Customer choice will be further increased when over 50 new entries are introduced over the next few years. These changes represent significant progress, even considering current program delays reported in the press.

North American automotive assemblers have spent the last two years organizing their supply chains to take advantage of the incentives offered in the Inflation Reduction Act. Significant BEV assembly and battery capacity increases have been approved, betting on stability through 2030.

These manufacturing incentives will produce 4.7 million units of BEV capacity by 2027, an excess of 1.8 million units. This capacity transformation has taken place in all three USMCA markets, with BEV increases in the United States leading the way.

One could argue that manufacturers were willing to go along with excess capacity if the government was willing to subsidize the transition. Yet, it will take time for this excess capacity to be utilized effectively. It will take BEV entries with lower prices than expected, lower battery costs with increased range and more public charging stations. These consumer requirements won’t be fully in place until the end of the decade.

On a positive note, manufacturing employment growth has already started. U.S. production of 10.8 million vehicles in 2024 increased automotive manufacturing employment to levels that are higher than 2018, according to Bureau of Labor statistics. Increased production is expected to boost those levels moving forward, for assemblers and suppliers.

Trump’s Plan Will Bring Turmoil

The Trump administration—based on their desire to increase tariffs, roll back planned emissions standard increases and eliminate incentives to produce and sell more battery-electric vehicles—is about to add turmoil and instability to the automotive environment at a time when the electric transformation is accelerating. The rationale appears to be that customers will have more choices than mandated regulations allow. (Spoiler alert: nobody makes a customer buy an electric vehicle, and U.S. consumers will have plenty of ICE/Hybrid choices through 2035).

Cancelling federal consumer incentives for purchases and leases will put the BEV incentives burden on manufacturers (and suppliers). At this stage of BEV development, it appears that a $7,500 consumer incentive funded exclusively by OEMs would be problematic. The elimination of consumer incentives would lead to less demand and lower capacity utilization. It will lead to more BEV program delays and push out BEV capacity increases by at least two years.

Eliminating the manufacturing assembly and battery production incentives will only make the situation worse. For the most part, investment decisions through 2027 are well underway. Incentive elimination will lead to employment disruptions in Michigan, Kansas, Kentucky and Tennessee, major hubs of BEV capacity and battery development already approved. For example, rather than running two shifts, manufacturers may elect to only hire one shift. These changes will also hurt U.S. tool and die makers when more programs are cancelled, and parts suppliers who were expecting two shifts of volume. At the same time, Chinese manufacturers will continue their global expansion.

Eliminating all incentives without increasing CO2 regulations at the same time would be a disaster for all manufacturers except Tesla. The disruption would be significant, as changes in all the regulations would not be implemented simultaneously. The baseline U.S. outlook would be relegated to the shredder.

Tariffs to the Rescue?

The potential disruption outlined above will be extensive. Unfortunately, it is not as bad as increasing tariffs on imported vehicles from Mexico and Canada to “bring production back to America.” As Trump stated to the Economic Club of New York on September 5, 2024, “We will bring our auto-making to the record levels of 37 years ago, and we’ll be able to do it very quickly through tariffs and other smart use of certain things that we have that other countries don’t.”

Achieving that objective is a moonshot. Fortunately, a more realistic level of expansion is already underway. There are currently three U.S. plants that will not be operating in the second quarter of this year: GM Fairfax and Orion, and Stellantis’ Belvidere. The good news is that each of these plants are scheduled to start production on battery-electric programs very shortly. Additionally, there are three greenfield plants that will come on stream before the end of 2027. There are also six plants that undergo ICE to BEV partial conversions during the same timeframe.

Will tariff increases help? The short answer is no. History has shown that tariff-induced supply chain changes take time to produce results. The 1981 Voluntary Export Restraint program lasted more than 10 years—and during that time, Japanese manufacturers installed significant capacity into the North American market. It didn’t happen overnight. It would take sustained tariffs over a 10-year window to get General Motors to move Mexico production to Fairfax and Orion, or to get Ford to move Mexico and Canada production back to Flat Rock or Blue Oval. That would be some serious heavy-lifting!

The expected result of increased tariffs will be increased prices on all light vehicles—imported and domestic. Remember, most manufacturers have a vehicle portfolio that encompasses both domestic and imported products. Taken together, these products have an established price and value ladder. Disrupting import pricing with tariffs (including parts pricing) will lead to a natural increase in domestic pricing. More to the point, home-market producers tend to use the tariff umbrella to boost prices and improve their own margins. Overall, first-quarter tariff increases will lead to a reduction in U.S. production as early as the second half of 2025. The size of the reduction will depend on the size and scope of the tariff.

Hint: Automotive suppliers should be reviewing their contracts for any pricing wiggle room due to increased costs

A Balanced Proposal: Growth, Revenue and Protection

The dual strategy of eliminating BEV incentives and increased vehicle tariffs will shatter the structure of one of the most important segments of the U.S. economy. Yet, there is a more rational approach to increasing production at U.S. assembly plants and providing an opportunity for a smoother transition to an electric future (and close some of the development gap with China):

First, push the existing CO2 standards out by five years. The 2030 standards would then be equivalent to what are now the 2026 standards, and then decrease at the rate in existing legislation. This would reduce potential penalties (or the purchase of credits) due to non-compliance. That money could be used for additional investment.

Reduce the consumer incentives to $5,000 for BEV and $2,500 for hybrid models that meet the local content requirements. The incentives would be in place until 2032. This would be the tradeoff for increasing CO2 emissions standards.

Implement a federal road tax for battery-electric vehicles at two cents per kWh. This tax would be applied at all public and fleet charging stations. Home charging would be exempt.

Eliminate the tax incentive for imported BEV vehicles.

Continue existing incentives for battery content and assembly requirements. Claw back any funds that have been provided if programs are cancelled.

The U.S. tool and die business has been significantly outsourced to China. Approve an incentive program for U.S. production of tool and die fixtures, injection tools and stamping dies. This would include funds to train a new generation of tool makers.

No additional tariffs on imported vehicles—from anywhere (China exception).

200% tariffs on all Chinese imports assembled in any country for 10 years. China has put in place BEV and ICE/Hybrid capacity increases that are far higher than home market demand; some estimates are as high as 100%. This should be viewed as a national security threat to the United States and our trading partners.

Taken together, these policies provide a better chance of achieving more U.S. production, a smoother transition to a battery-electric future, and boost long-run development expertise. Conversation among all stakeholders is required.

A flurry of day-one executive orders on tariffs and regulations won’t get the job done and could lead to serious unintended consequences.

About the Author

Warren Browne

President, RFQ Insights

Warren Browne, president of RFQ Insights, has held senior executive positions at General Motors Corp, working in six countries over a 40-year career with the automaker. He is currently an adjunct professor of trade and economics at Lawrence Technological University.