A Service Economy Is No Substitute for Manufacturing Innovation

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

Since the 1980s, when Japan Inc. started challenging America’s hegemony in making stuff, economists have questioned the need for us to make anything at all anymore. Case in point: Jagdish Bhagwati of Columbia University, who denigrated those pressing for a stronger American factory sector as suffering from a “manufacturing fetish.”

The rationale is always the same: Western nations have “matured” into service economies and can purchase goods from overseas.

If I have a manufacturing “fetish,” so be it. There’s a fundamental reason why a nation’s manufacturing base remains an important societal goal: Innovation is the key to productivity; productivity is the key to higher living standards – and nothing drives innovation or productivity more than domestic manufacturing. Nothing.

I raise this issue because this is the 20th anniversary of a seminal paper on this precise point, and over those two decades a growing number of economists have echoed the sentiment. More politicians pay lip service to manufacturing as well, tying it to the creation of middle-class jobs. But this doesn’t capture the much broader economic value of having a vibrant industrial base.

In 2003, I oversaw a study by noted economist Joel Popkin titled “Securing America’s Future: The Case for a Strong Manufacturing Base.” This research went a long way to connect the dots between manufacturing R&D, innovation and increased living standards. And those links are just as valid today.

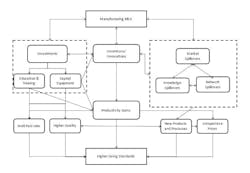

Accompanying this article, you’ll see a very simple flow chart that illustrates the connection: Higher living standards start with an idea, which spurs manufacturers to invest in R&D, which leads to a variety of innovations. These innovations incentivize manufacturers to invest in human and physical capital, which also create “spillovers” that benefit other parts of society – from competitors to suppliers to other sectors. All of this leads to productivity gains, and in turn to higher-paying jobs, higher-quality products, new products and processes and more competitive pricing. Ultimately, citizens experience higher living standards.

It's a simple formula, but many politicians and economists miss the forest for the trees. They count manufacturing’s number of jobs and its portion of GDP, and they conclude that manufacturing is important – but they don’t acknowledge the broader impact it has on living standards.

As stated above, it all starts with manufacturing R&D. While the latest data shows that China is closing the gap in terms of R&D investments, the United States remains the biggest player here: the U.S. annually spends roughly $680 billion on R&D, compared to $550 billion by China. After China, the U.S. spends more in R&D than the next seven countries – Japan, Germany, South Korea, France, India, the U.K. and Russia – combined.

This is important for all manufacturers because the spillover effects of innovation are linked directly to R&D. Product and process innovation generated through R&D spending in manufacturing affords advantages not just to its network of suppliers, designers and engineers—the benefits spill over across society. And companies are more likely to profit from spillovers when R&D takes place in geographic proximity—that is, in a localized region, especially for benefits from more generalized R&D. Hence the need to keep a dynamic domestic manufacturing base.

This is further demonstrated in the book Producing Prosperity, by Gary Pisano and Willy Shih, published 10 years ago. The Harvard Business School economists argued that policymakers need to focus on helping American manufacturers innovate. Their perspective – that manufacturing innovation is most likely to occur within America’s “industrial commons” – was not new, but lent further proof that manufacturing is much more vibrant in communities of manufacturers, suppliers, research labs and skilled talent in geographic proximity that support each other and lay the foundation for such innovation. Such clusters can provide a region – and a nation – a competitive advantage.

The point here is that experts generally agree that innovation is the foundation of economic growth that leads to higher living standards. And manufacturing, the sector in which people simply make things, is home to more innovation and outside-the-box thinking than any other sector. In the mid-21st century, that includes the technology sector.

Unfortunately, over the past two decades these industrial commons have started disappearing from our shores. From machine tooling to LED lighting to rechargeable batteries to semiconductor production, much of this nation’s technological knowledge and infrastructure has left for Asia. As we saw during the supply chain disruptions of the pandemic, that can have serious consequences for businesses and consumers. It’s time to adopt public policies that will keep manufacturing here.

Stephen Gold is president and CEO, Manufacturers Alliance.