In Youngstown, It Takes a Village

It was news heard around the world: 4,500 manufacturing workers from Youngstown, Ohio, and the Mahoning Valley region lost their union jobs when General Motors’ iconic Lordstown Assembly plant, builder of the Chevrolet Cruze, shuttered in 2019.

Some expressed surprise that there were any plants left to close in Youngstown. The city’s protracted economic decline can be traced back to Sept. 19, 1977, a day that locals call “Black Monday,” when Youngstown Sheet & Tube, paternalistic employer of 5,000, announced it was pulling up stakes and moving operations to Tennessee. The decades that followed were dimmed with more plant closings, and Youngstown has lost half its population since.

GM, however, soon had a new tenant for the empty Cruze plant. Lordstown Motors, an electric truck startup, moved in with a plan to build an electric pickup and hire 400 workers within the year. Because everyone likes a hard-luck story with a redemptive twist, the company’s arrival generated media coverage and high-profile politican visits.

Unfortunately, Lordstown’s processes, people and physical operations were nowhere near fully formed, and a fraud investigation, missed deadlines and a truck catching fire during a big unveiling haven’t helped matters.

But that story is for another day. This story is about Youngstown, a 1900s industrial boomtown that deserves a new narrative: A narrative where a global automaker (GM) and a battery manufacturer (LG) charter five barges to bring supplies and equipment from around the world to build a new plant (Ultium). A narrative where a sprawling ghost city is reimagined as a bustling midsized region. Where new technology is welcomed and the void from Big Auto/Big Steel is filled with innovative small- and medium-sized manufacturers in a cross section of industries that drive the economy.

All of these things are happening to different degrees in Youngstown: The battery plant is opening (the ships were enlisted to circumvent recent supply chain challenges), savvy smaller manufacturers are thriving, and the opening of America Makes—Additive Manufacturing Institute and Youngstown State’s Center of Excellence for additive research has business leaders thinking about new industrial clusters.

“This is a region that kept losing and losing and losing,” says Ethan Karp, president and CEO of MAGNET, the northeastern Ohio Manufacturing Extension Partnership whose region includes the Mahoning Valley (of late rebranded as “Voltage Valley”). “I think that people’s attitudes are changing. I feel like we’ve definitely gone from a ‘Woe is me’ type attitude to, ‘We can do this.’ Let’s get additive manufacturing here. Let’s get energy storage out here.”

If the momentum grows, Youngstown’s work toward building a new economy by resetting its manufacturing strengths—employers who value mechanical skills, strong engineering and trade schools, tribal knowledge--could also serve as a blueprint for other legacy manufacturing cities that won’t attract, say, a Google headquarters, and can’t sustain themselves with a lower-wage service economy.

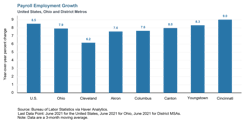

“Manufacturing is one sector that’s holding its own in Youngstown,” says Rick Kaglic, a former Youngstown machinist himself who is now a vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Kaglic notes that since the pandemic downturn, “job growth in the region has kept pace with the national average. And it has actually outperformed some of its peer cities, such as Akron, Canton and Dayton. So at the end of the day, quite a bit of progress has been made. But there’s still a lot of room to improve.”

The Battery Makers

Just past the old Cruze plant, a mini-city of construction trailers heralds the arrival of the Ultium Cells LLC plant, a GM/LG partnership in electric vehicle battery-cell manufacturing. It is scheduled to start production in 2022 with 1,200 employees, including 1,000 production workers making a starting wage of $16 to $22 an hour plus performance incentives. The continuous 2.8 million square foot facility is currently about 70% complete, with just 2% of equipment installed. The plant has the capacity to make untold millions of cells per year for GM and its partners.

The plant’s leader, Thomas Gallagher, Ultium vice president of operations, is a 31-year GM veteran with leadership experience at four GM plants. “This is quite a different business,” Gallagher says. “It’s not automotive. It’s a chemical business and how we manufacture and make battery cells has some different competencies.”

While hiring engineers and getting a business team in place are Gallagher’s current priority, he’s received “thousands” of applications for a variety of roles. Youngstown State University is the main feeder school for engineers, with nearby Kent State University and Cleveland State University and the University of Akron also in the mix. “The idea is that people that are from the community or have experience with a community are more likely to want to stay with the community,” Gallagher says.

On the recruiting side, Gallagher and his team have been hosting educational meet-and-greets at malls, churches and community centers as well as schools. The groups see and hear what a battery cell is, watch videos of the manufacturing process and learn about career opportunities. “We’re trying to take our story out there, rather than just rely upon an internet posting system,” says Gallagher.

He’s expecting all hires will need training in both technical and soft skills. In August, some 40 members of the launch team were in Holland, Michigan, training with LG on running equipment and the battery process. Other skills-based training is happening through partnerships with Youngstown State and Eastern Gateway Community College.

“People can grow—that’s the other piece,” says Gallagher. “It’s not like you come in at a wage, and that’s what you’re gonna make for the next 20 years.”

Jenny Hawkins, an associate professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, says a plant like Ultium isn’t a panacea for the area, with 1,200 workers vs. the Cruze plant’s 4,500 and a $16 starting wage that “seems a little low, with what’s happening with restaurant wages.” But the smaller steel and components companies that are still chugging along in Youngstown, plus momentum in “all these different little industries with electric vehicle batteries, electric vehicles, additive manufacturing” have critical mass. The fact that the city is much smaller in population than it used to be can actually work to its advantage: “With respect to growing your economy, that’s a lot more manageable to work with,” she says. “And if the 1,200 jobs they are creating [at Ultium] are for highly paid educated people, that will help the economy.”

The SME

Taylor-Winfield, a machine builder 30 miles from Youngstown in the village of Leetonia, is a legacy manufacturer positioning itself for the future. TW dates back to the late 1800s, when the Mahoning Valley was the steel capital of the world. It’s so old its Facebook page features an historic photo of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison standing in front of a TW machine.

Today, TW is still supplying steel mills with specialized heavy-duty welders, but half of its business is based on non-steel-related equipment that involve automation, induction and resistance. Global manufacturers (big names you would recognize) hire TW to design automation systems. And so has at least one tech startup. TW is currently working on automation for a startup in California that makes 30-year-lifespan hydrogen and precious metal rechargeable batteries that have been used in space and is developing more affordable/sustainable rechargeable battery banks for automotive. The TW machines will weld the battery cylinder to speed up production and lower cost.

TW’s workforce—some 150 machine builders, welders, engineers and support people--is on track to grow 15% this year, and this year’s bookings exceed last year’s by 35%. TW President Donnie Wells said growth is limited by the availability of the labor pool and that Youngstown’s population needle is not ticking upward. “Youngstown continues to live off of the infrastructure that was built in post World War II, and there’s not enough [good housing stock] and the population has been in a consistent 4% decline year over year for a while now. There needs to be a multispectrum view of, ‘How do you attract and keep the next generation?’”

Wells is not hiking wages, however—TW pays around the same as local talent competitors—reasoning that people work there for the family atmosphere. “It’s more than just a transactional relationship,” he says. “If you are looking to be treated as a human being and highly valued, and you’re OK with not making top dollar, then it’s a good fit.”

The Taylor-Winfield crew

TW partners with the Mahoning Valley Manufacturing Coalition (MVMC) to recruit and train workers. Jessica Borza, executive director of MVMC, says that manufacturers in the region “have openings, and many of them have a great number of openings.”

With demand high, MVMC is getting creative with its tactics to attract and train locals. Borza is excited about a new initiative that involves “truly going door-to-door and talking to people in neighborhoods, at the coffee shop, the grocery stores about manufacturing job openings, and getting them connected.” The MVMC has tinkered with this program, called Work Advance, for a few years “and we’ve done a lot of different types of outreach in the schools and the community through social media, but we still felt like we were missing something.” The recruiters are visiting places with more women and people of color, and leaving no stone unturned in rural communities. “I was talking to one of the recruiters, and he showed me a Facebook video that he had filmed, where he was talking with a couple of young women who were on horseback,” says Borza. “And they hadn’t considered manufacturing—maybe as young women it just didn’t cross their mind. There were a lot of questions, and now he’s got a connection with them.”

Borza doesn’t have any numbers to share yet on Work Advance’s progress. With the grassroots approach, “I always go more toward the qualitative aspect of things. Because that program has the potential to change lives in ways that you and I might not think about on a regular basis. People are getting connected to these great jobs, and potentially having health and dental benefits that they never had before, retirement benefits that allow them to think about a secure future, being able to buy their own truck, to buy a car. Things that for whatever reason, they did not see for themselves before they were introduced to a career in manufacturing. And that’s pretty powerful stuff.”

Additive and Beyond

No story about Youngstown manufacturing would be complete without mentioning America Makes, the national Manufacturing Innovation Institute that focuses on additive manufacturing research, and Youngtown State’s Center of Excellence, which among other areas of manufacturing technology trains students and professionals in additive careers.

Creating an additive hub has not translated to huge job growth in Youngstown. At least for now, its benefits to the region are more abstract. “The reality is that except in a few rare cases, focusing solely on technology is not necessarily the recipe for explosive local growth,” says MAGNET’s Karp. “Except where it attracts high power OEMs to locate there, which in additive’s case, I don’t think has happened.”

Karp highlights a small manufacturer called M7 Technologies. Founded in 1918 as a bronze castings producer for the U.S. steel industry and then shifting to precision measurement, it recently pivoted again to build one-of-a-kind additive machines (including one of the world’s largest 3D printers) to manufacture specialized parts through a spinoff, Center Street Technologies. Companies from all over the U.S. are partnering with M-7 for prototypes and custom additive production.

The biggest benefit with efforts like America Makes “is that it puts manufacturing innovation on the map in Youngstown,” Karp adds. “It reminds companies that the community has a manufacturing base and that manufacturing base is focused on technology and innovation. That means that it is more likely for any company to want to locate here. Companies say, ‘There’s something going on here, this isn’t just a town that’s in decline. This is a town that’s reinventing itself.”

The coda here is best described with a steel-making process: Youngstown is in the ingot stage of its transformation. It’s still at the foundry. It will take a long time to see the results. But the energy is there, the fire is lit, and the engines of transformation are rumbling.