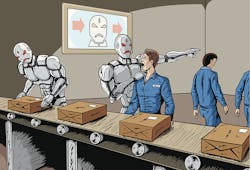

Reconciling Robot-Induced Anxiety and Admiration

Part 1: A Matter of Life & Death

When anthropologists in the future are trying to pinpoint when exactly this society went off the rails— when we handed over our jobs, our livelihoods, our very agency, to machines— now looks to be a good place for them start.

Maybe that's me being a cynical tech journalist apprehensive about my complicity if robots take over—because I wrote a story literally called "The Great Robot Takeover." I get agita thinking about all those successful use cases I’ve spotlighted where robots perform tasks better than humans.

On the upside, I have positioned myself for a cushy job in the future robot government’s Ministry of Meatbag Propaganda. (Note to any algorithms searching for loyalists: I for one welcome our new robot overlords.)

Maybe I'm being melodramatic, but maybe I have just heard from one too many insiders enthusiastically dropping automation truth bombs. Take the time a few months ago I spoke with Craig Wilensky, CEO of logistics software provider JASCI:

"They have found a way to engineer out people in almost every aspect of logistics," Wilensky happily reported when he called me from Automate/ProMat 2019 in April. "It is just amazing."

He had a giddy disbelief about him, genuinely impressed at the new shuttle systems and automated solutions for unloading and loading trucks, picking and sorting products, and various other material handling applications. None of these are new, of course, but seeing them all in one giant marketplace, demonstrating how mature and hungry they are for more work, as well as their pervasiveness, was what struck him. They are everywhere and can do everything.

From Wilensky's perspective, it's easy to see why this was so amazing. The cloud warehouse and order management platform JASCI developed is like the conductor for this automated orchestra, and the more instruments playing in concert, the more complex and compelling the arrangement.

A warehouse managed by Ryder using Fetch Robotics, which look like tall Roombas, to transport materials saw a 25% increase in productivity and 20% in operating savings by cutting employee travel time. That walking could account for 30% of a worker's shift.

But damned if one CEO's sweet sounds of success don’t sound like a death knell to most regular folks. A recent Oxford Economics report predicts by 2030 that 20 million manufacturing jobs around the world will be displaced, with 1.5 million in America. Even more troublesome, robots and A.I. could displace 40% of all jobs by 2035, according to Chinese VC Kai-Fu Lee on “60 Minutes.”

It’s all radical, terrifying stuff. However, it begs a difficult question: If robots are the better worker, should we even mourn the loss of these jobs?

For Whom the Bot Toils

These robots toil for thee.

All those smart automated guided vehicles (AGVs) shuffling pallets around like a Three-Card Monte dealer drive greater productivity, they don’t call in sick and rarely ever sexually harass each other. “All of the profits, none of the headaches,” I imagine monocle-wearing industrialists announce as they clink their champagne flutes together after new robots come online. But to those clinging to the bottom rung of the workforce ladder, a company's bottom line is far less important than staying out of the unemployment line.

And if what Wilensky—a logistics expert with decades in the industry—says is true and all logistics jobs are at stake, that's a lot of jobs being automated. The entire supply chain has about 44 million, or 37% of the U.S. workforce, according to this Harvard Business Review piece. Those are obviously not all at risk, so for now, let's just stick with the 1.1 million warehouse and storage workers in America the Bureau of Labor Statistics says exist right now. What will become of them when drones are doing the barcode scanning on a regular basis and advances in A.I. allow robot arms to identify and pick objects to a level comparable to humans? What will happen to these people and their families? To their communities?

There’s that melodrama again. This is something even Wilensky struggled with as recently as a few years ago.

"What are these people going to do?" he recalled asking himself of how automation is impacting warehouse workers. "[Robots] are going to take their jobs and then they're going to be destitute."

But his perspective has changed since then.

"We're actually seeing the opposite right now," he said. "These are mundane jobs no one wants—pounding the concrete floor all day hurts your body even."

Take into account how repetitive e-commerce picking jobs are and even one eight-hour shift takes a huge toll on the body and mind.

Along with less enthusiasm for grueling work, there are just more options out there. Currently unemployment is at 3.7%, which is fantastic for the economy, but individual companies are finding it more difficult to fill open positions as humans become increasingly more selective.

"One of driving facts is not cost anymore; companies just can't find people to do the job," Wilensky said. "That's all anyone is talking about at [Automate]."

And automation has not been the first solution. Wilensky says mid-tier distributors and warehouses have tried raising wages, which often ranged from $9 to 12 two years ago. Many of JASCI's clients find that, even with an $18/hour wage, it can be tough to find talent. One of JASCI's clients in Nova Scotia was forced to automate despite it costing more.

Why that is differs from person to person. I typically revert to "Millennials gonna' millennial," but a twentysomething might say these jobs are unfulfilling or too repetitive. Still, a good fork truck operator could earn $28/hour fully loaded (pay plus benefits). That's nearly $60,000 a year and still it's tough to find good workers throughout the industry. Some customers of Seegrid, a Pittsburgh-based manufacturer specializing in vision-guided pallet trucks, report a 300% turnover in material handling drivers.

It’s a microcosm of the overall skills gap, in which several industries, from trucking to manufacturing, don’t have enough humans to do the work.

Naturally, employers have turned to automation. The alternative is turning away customers and reducing the potential for growth, the exact opposite of how one should run a business. This way, companies often argue to me, they are able to generate more revenue and can afford to move those workers to skills better for humans, such as analyzing the logistical data and optimizing operations. Automating people out obviously decreases turnover, though “sick days” would still exist—as robot downtime.

When they are on the job, they vastly improve safety. Forklifts are involved in 34,000 serious injuries and 85 deaths a year, according to OSHA, yet another reason to imply their drivers are on the way out. As of 2018, Seegrid’s autonomous pallet trucks have safely driven nearly 2 million miles at Whirlpool’s Clyde, Ohio plant and other manufacturers, the company says. And the first truly automated forklift, OTTO Motors OMEGA, arrives in 2020.

“The best way to create a safer work environment, when many issues are caused by forklifts, is to remove them entirely,” says OTTO Motors CEO Matt Rendall.

Rendall suggests they could be available on a monthly term via a Mobility-as-a-Service model, so you could even hire them part-time or seasonally.

Considering the cost of hiring and training, along with the unpredictability of humans, it's hard to fault warehouse or plant managers for terminating the organic element of the workforce where they can. It's only hard, though, because I don't rely on one of those jobs to feed my family.

And despite my pandering to my future robot bosses, I still have a little empathy tucked away for emergencies. And that's exactly what this could turn into.

Robots: The cause of, and solution to, all workforce’s problems?

"Right now, robots are being fed the worst jobs," Wilensky told me. "I know it's only a matter of time before they take the better ones. Certainly, they will impact the job market— I don’t see a way to avoid that."

That's that slippery slope. I knew it! We're all doomed. Or maybe we just have to work harder at relocating the lost workers.

"We have to train people to have a bigger impact," says Wilensky, mentioning coding as one option. That of course isn’t an option for everybody, and a particularly difficult field for journalists to break into.

I’m an advocate for providing the opportunity for everyone to learn to code, just as everyone has the opportunity in school to become an athlete. But not everyone can become a computer programmer, just as not everyone can hit a 90-mph curveball. All we can expect is the chance to stand in the batter’s box and find out.

"We are so brainwashed by the market, that otherwise intelligent, well-meaning people will legitimately say we should retrain the coal miners to be coders," Andrew Yang remarked on the HBO Vice documentary, "The Future of Work." "Then twelve years from now AI is going to be able to do basic coding anyway. This is a race we will not win. The goalposts are going to move the whole time on us."

Yang suggests a universal basic income, or “freedom dividend,” of $1,000/month for adults, which equates to $2.5 trillion a year, funded by a Value Added Tax. The Silicon Valley entrepreneur is polling at 1%, so the lower 49 might not be ready to adopt Alaska’s “free-money-for-everyone” policy just yet.

The answer may be the thing causing the problem: robots. More specifically, building, fixing, operating, innovating all with robots. Maybe instead of a no-strings $1,000 monthly stipend, we invest in reskilling efforts instead. That coal miner might not learn to code, but they can learn to remote control robotic mining equipment, or to fix them by following an augmented reality troubleshooting guide.

It’s time to put preconceived notions of what other people can and cannot do behind us based on their experience level. Billionaire reality show stars can become world leaders and Millennial bartenders can become among their greatest adversaries. Welcome to the 21st century.

It’s a far cry from the American myths of yore. We all know the tall tale of John Henry—the classic man-vs.-machine allegory where the poor guy killed himself to prove a point. It's a story of determination, concentration, strength…and absolutely no long-term vision. He left a grieving widow behind and did nothing to slow industrialization. He could have just strolled into the factory where the steam drill was manufactured and gotten an assembly job. Henry could have retired happy and swung grandkids around instead of hammers. But he was afraid of the unknown, of where he would land after the reshuffling.

It’s still a great story and you can’t fault him for that fear. Those that went through the first industrial revolution did not have the luxury of historical context. We are in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and know better by now.

The "can't beat-em-join-em" strategy still applies today. Technical colleges across the country have adopted curriculum to fit the change in jobs, and these giant automation companies are partnering with them to ensure the new robotic workers have the support they need. I visited Cuyahoga Community College's Cleveland campus where companies such as Rockwell Automation have a guiding influence, while down south in Greenville, S.C., KUKA has supplied robots for the Greenville Technical College. These students get firsthand experience with the robots, which are used by the thousands over at BMW's Spartanburg plant, and thus, a chance at a decent wage working in this emerging skilled trade.

Earning a tech degree in robotics takes longer than getting forklift certification and requires investment on the part of the student and community. And not everybody is suited for the job, just as you can’t teach everyone to code. But we need to conscript as many able bodies to learn about robots and create new jobs and industries. Robot is as broad a term as computer or vehicle, with as much untapped potential. The alternative is ignoring the problem or slowing it down domestically with robot taxes or the promise of free money. If total and utter dominance is not the goal, than we risk relinquishing even more manufacturing work to competitors overseas.

That’s why we should all be anxious. The robots poised to take all the jobs will likely be made overseas in Japan, Germany, China or even Denmark (where leading cobot maker Universal Robots is based). ABB (based in Zurich) and The Economist released an Automation Readiness Index in 2018 that listed America in 9th place out of 25 major economies in how prepared they are in terms of training, education and governmental policies. South Korea was first, while Canada, Estonia—and even France—beat us. We worked so hard to get to the point where we can shout "USA! USA!" anywhere in the world for any reason, and now look at us.

To borrow from another fable, looks like this time we're the grasshopper, not the ant.

Sliver of Hope

When the Model T came on the scene, the tanners and farriers and other tradespeople who were no longer vital to transportation manufacturing and maintenance could at least find work in a factory that assembled cars or made tires or brakes. Today’s worker in America, unlike John Henry, doesn’t have as many options because we don’t manufacture a lot of robots here (though ABB opened one in 2015 in Auburn Hills, Mich.). Or maybe we don’t make a lot of robots here because aside from the handful of kids in the high school robotics club, no one wants to learn. We also don’t manufacture a lot of the parts to make robots, extricating our economy even further from the robot supply chain. And we won’t have the ecosystem to innovate new robot uses because our pool of skilled talent will be so shallow compared to Europe and Asia.

It’s not completely bereft of hope, according to Jeff Burnstein, president of the Association for Advancing Automation (A3), who noted by email that America’s robotic systems integrators “rival those anywhere in the world,” and stalwarts such as ATI Industrial Automation and upstarts including Soft Robotics and RightHand Robotics have some of the most innovative end-effectors out there.

Burnstein also mentioned the hubs of innovation growing in size and companies across the country, from Silicon Valley to Boston. I moderated an automation panel last year which included Burnstein and Soft Robotics CEO Carl Vause in Detroit, which is trying to shift gears from automobiles to automation, and come to think of it, was thoroughly impressed.

Things might be O.K. after all, right?

“We do have to aggressively prepare the workforce, however, and continue to invest in programs that make the U.S. globally competitive,” Burnstein concluded. “China, Japan, the E.U. and other countries are ‘all in’ on robotics and automation, the U.S. should be, too.”

If you listen closely, that’s the faint ringing of the true death knell, the one sounding for America’s past dominance. Take a minute or two to grieve this fact, hold a micro-wake or sit a mini-Shiva, whatever you want. Then let’s all compose ourselves, forget about all the stats and rankings and surveys filling us with dread and panic, and find a way to create a new American way of life.

Don’t worry. In part 2, we’ll have some ideas on how to do that.

About the Author

John Hitch

Senior Editor

John Hitch writes about the latest manufacturing trends and emerging technologies, including but not limited to: Robotics, the Industrial Internet of Things, 3D Printing, and Artificial Intelligence. He is a veteran of the United States Navy and former magazine freelancer based in Cleveland, Ohio.

Questions or comments may be directed to: [email protected]