John Kawola began working in the additive manufacturing space in 1997, a time when decent 2D printer could cost several thousand dollars. He worked his way up the Z Corp ladder, residing as CEO for four years, until the company was acquired by 3D Systems in 2012. He left the 3D printing world to run an automation company and few other ventures. During his hiatus, 3D printing exploded. Hundreds of new companies, startups and crowdfunding campaigns sprang up, only to be clobbered back down by the reality that consumers weren't ready for the manufacturing tech in their homes, and might never be.

One of the last companies standing, Ultimaker, enticed Kawola back into the fold as their North American president in 2016. The Dutch-based company had always focused on catering to industrial applications, where additive manufacturing is mature enough to concretely provide instant value. By the end of the year, Kawola's crew introduced two new desktop models, the Ultimaker 2+ and Ultimaker 3, now workhorses in many colleges, innovation lab, and even the factory floor itself. Last year, Volkswagen's Portugal plant saved $377,000 last year by 3D printing wheel assembly jigs and fixtures, as opposed to waiting long periods while replacements crawl through the supply chain.

"It used to be if they wanted one of these parts, it would cost $200 to get the part, and it would take a couple of weeks," Kawola says. "Now they can print it in a couple hours and cost $20."

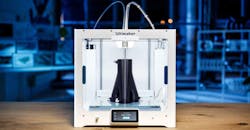

This year, Ultimaker unveiled a bigger, easier-to use desktop called the S5, poised to take a chunk out of this magic number: $420,706. That's how much they calculate is spent a minute by the auto industry. If the industry additively produces even a few parts right there on the floor, that could down at least a few minutes here or there.

We talked to Kawola about the evolution of 3D printers and the value they have to manufacturing now and in the future.

JH: How did Ultimaker succeed while so many other 3D printing companies that failed?

John Kawola: Companies that ceased to exist chased applications that were not real. We never spent that much time betting the farm on the consumer. And at least today, I think the consumer market is limited to a pretty hardcore enthusiast. It was the person who already had a lathe in their basement and already was making things and was familiar with some software.

I think the biggest transition for us as a company was from initially selling inexpensive 3D printers primarily to schools, fab Labs and makers to selling predominantly to the enterprise, including big automotive companies, industrial design and architecture firms.

The reason that's happened is the quality of the product, the quality of the materials and the range of the materials that you can use. The ease of use has also improved quarter over quarter, year over year.

So now printers are being seriously considered as a supplement over adder, or as a replacement for traditional processes. The previous wave of industrial 3D printers cost $50,000 to $100,000 dollars. But I think for some applications and some uses, the $5,000 desktop printer is just as good as what the $50,000 printer could give you a few years ago.

JH: When I visited Jabil's Blue Sky innovation lab, I saw they had a whole wall of Ultimaker 3's being used to make section of a prototype, instead of tying up one giant printer priced over $200,000.

JK: Jabil is a good example of a customer who was pretty well aware of all of the technologies that were out there and saw desktop printers like ours and said, "If we put a whole bunch of these together, for one, they'd be a lot faster and two, it'll be a lot cheaper."

And the entry point, the cost of that first one or two or three or five, is not that much. So they, like a lot of people, said, "Well let's try it.' Maybe it will work, maybe it won't. If it doesn't, it's not a big deal. But I think increasingly it does work for some of those applications, and then they're heroes because they were able to find an alternative that was a lot less expensive than what they had before.

JH: What's the difference between your different printer?

JK: The Ultimaker 2+ has been in the market for a few years now. It's single extrusion, not connected, but a great workhorse, with entry price points about $2,500. It has open materials, open software, actually open hardware as well. So that's sort of the baseline.

The Ultimaker 3 was our first step into dual extrusion, so you can do two materials at once. You can do two colors at once. You can build material and support material for more complex geometries. It's also connected to Wi-Fi or LAN. And then there were some other automation features in terms of bed leveling and automation that made it sort of a step above what the Ultimaker 2+ was.

The S5 is another iteration in terms of automation. It's bigger, has a much easier-to-use screen in the front, what we call filament close sensor in the back to actively track how much materials being used, or to tell you if you're running out of materials. It also has a more robust material flow path, so you can use more abrasive engineering materials like carbon build materials and glass-filled materials. So those are the differences in how the product is evolved over the last two and a half years or so.

JH: How does having your 3D printers being connected and providing data improve the customer experience?

JK: Over time we can start to see what people print and we can start to see which prints are successful and prints are not. And sometimes that may not be successful because the customer didn't orient in the right way. Well, maybe he didn't know. Maybe he needed to be trained. Over time our software can get smarter and smarter by not just doing the physics, but also empirically gathering enough data to say parts that are made a certain way are successful or not. We can build that into our software to give the customer a better chance of success.

JH: Now about this automotive cost per minute study. How did it come about and what did it tell you?

JK: The study came from a collective gathering of feedback from customers, where we looked at cost [based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and auto industry revenue].

When we looked at the data, it caught our eye how much the cost per minute is. The exact numbers don't matter. Every minute counts here. Now, we are presenting the argument about how any type of productivity tool, in our case a 3D printer, has meaningful impact on a large industry if it can save a minute, an hour, a week, a month collectively. And small industries, too, for that matter.

If a company is a month late launching their new car, that’s a month's worth of revenue. People say, "Oh you'll get it back."

You don't get it back. It's a month of revenue that you just lost. And therefore, a month of gross profit that you just lost because you were a month late.

This is true even for a company like Ultimaker. We're a company with tens of millions in revenue per year, bumping up against $100 million. So one month for Ultimaker is between $5 million and $10 million.

Imagine for the automotive industry. Are 3D printers going to make that much of an impact in an automotive factory and automotive design cycle? I think we'd be stretching if we said that, but you take all these productivity tools and collectively they can make a huge impact.

JH: And as Volkswagen showed, this is happening now.

JK: We've seen a couple of cases in the last few months of big companies wanting to bring a handful of 3D printers on the floor. It's is very much the Jabil case study that was released recently that showed 80% reduction in production time. It allows the person on the manufacturing floor to make modifications in CAD and print something out and make a change versus a somewhat inefficient method of going back to whoever made the fixture to find the CAD file. Maybe it's somebody upstairs, or maybe somebody across the world. This is a way to try to get that as close to the manufacturing floor as possible.

I was in a factory and they had all these clamps and brackets they would get from their supplier to put on their production lines. They would bring over every single one of them to their little machine shop and they cut off different sections of the clamp.

We asked, "What are you doing?" And they replied, "We get these and don't like them, so we cut off this piece and this piece." They did this instead of actually calling up the guy and saying, "Hey, could you change this?"

So here's an example these guys doing this manufacturing for themselves. They're going over to the bandsaw and modifying these things. It's inefficient and crazy. But that would be better than trying to go find and communicate internally with a company. If they can have a 3D printer to do that, and if the printed plastic part can be accurate and strong and useful enough for them, then they would prefer to do that.

JH: On-the-fly toolmaking is certainly important, but are we close to 3D printers being used widely for end-use parts?

JK: We see a product today that's generally designed for the carpet, or the office design environment. But if you truly want a tool that is optimized for the concrete floor, you probably need another sort of wave of engineering materials.

Right now our printers are pretty fast, but for prototyping applications, the demands are not that high. If you can get the part in four hours or by tomorrow, they're pretty psyched. But on a production floor, they want higher throughput. So we see future iterations of Ultimakers that will be better optimized for that environment.

About the Author

John Hitch

Senior Editor

John Hitch writes about the latest manufacturing trends and emerging technologies, including but not limited to: Robotics, the Industrial Internet of Things, 3D Printing, and Artificial Intelligence. He is a veteran of the United States Navy and former magazine freelancer based in Cleveland, Ohio.

Questions or comments may be directed to: [email protected]