How a Flexible Supply Chain Delivers Value

Four years after the recession imposed corporate belt-tightening around the world, we see U.S. companies operating at near-record peaks of efficiency. The downside? These cost efficiencies have in many cases eroded supply chain flexibility. As demand dropped during the recession, many businesses trimmed inventory levels and cut costs in supply chain operations. Today, these businesses are finding their weakened supply chains can’t keep pace with economic recovery.

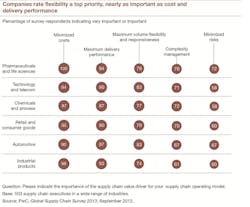

As a result, organizations are rethinking their supply chains to craft a strategy that can deftly accommodate broad swings in demand and supply. In fact, 64% of respondents to PwC’s recent Global Supply Chain Survey said they plan to implement greater flexibility to better respond to shifts in volume. That makes flexibility a top supply chain priority this year (see chart below), just behind maximizing delivery performance and minimizing supply chain costs.

A number of factors have converged to advance supply chain flexibility to the top of the agenda. Emerging economies, for instance, are expanding at double-digit rates, and with that growth comes a global shift in demand patterns. These swings include changes in physical footprints and material flows, as well as demand for more tailored products with a faster order-to-delivery time.

At the same time, competitive factors related to cost, speed-to-delivery and customer experience are increasing the complexity of supply chain management. Supply chains also are vulnerable to disruptions caused by natural disasters, political unrest and port strikes in the United States.

Companiesare under increasing scrutiny by watchdog groups, the media and social media-savvy consumers to uphold labor conditions and sustainability practices across supply chains that are becoming much more complex due to geographic dispersion.

For all these reasons, a flexible and visible supply chain has become an imperative in today’s business environment. Getting there will require that companies prioritize supply chain operations and tightly align them with other business functions.

To underscore the strategic significance, some companies have elevated their supply chain leaders to C-suite status. These new strategic leaders, with titles like Chief Supply Chain Officer and Chief Procurement Officer, represent the supply chain among business groups and suppliers. As such, they require skills in finance, human capital management, conflict resolution and relationship building, as well as technical knowledge and operations experience.

A flexible supply chain organization requires not only a strategic leader, but also input from managers who represent the traditional supply chain functions of planning, sourcing, manufacturing, logistics, and also sales and marketing, among others. This enables the supply chain organization to work closely with these potentially disparate business groups to better understand their individual operations, goals and deadlines.

Tight Integration with Business Units and Suppliers

Integration of the supply chain organization with other functions and across the extended supply chain is the bedrock upon which flexibility will be built.

A supply chain that is integrated with other business functions is especially important as companies enter new markets and launch additional products, adding suppliers and processes along the way. An integrated organization enables the company to map out supply chain processes as products and services are designed, rather than after the fact. For these reasons, a flexible supply chain organization should include decision-makers from product and service development, marketing and sales, finance, sustainability, ethics and compliance. This approach is an extension of the “design for manufacturing” concept that has been around for some time. Flexibility is gained by designing a product along with the supporting supply chain processes, and this can be a key differentiator.

At the same time, some organizations are extending their planning to external organizations such as contract manufacturers, third-party logistics providers (3PLs) and even customers. One thing is certain: Real flexibility demands strong, collaborative relationships with key suppliers and supply chain partners in order to jointly address capability gaps and help mitigate supply chain risks.

To get there, companies should first identify strategic and core suppliers that are central to business strategy and operations. These strategic suppliers will require a more targeted investment in development and management than transactional suppliers of commodity goods and services.

Collaboration is Critical

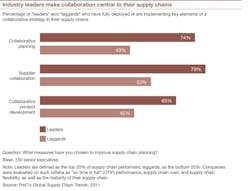

The leading supply chain organizations work closely with their strategic and core suppliers on issues that range from financing to emergency contingencies to labor and environmental concerns (see chart below). Tight collaboration enables organizations to better avoid risks, identify problems early and resolve issues quickly. Many companies, for example, proactively alert suppliers immediately when demand and production changes are likely. Stronger collaboration can also help lessen the bullwhip effect—supply chain variability at the various points in demand in excess of actual demand variability—that can result from many actions taken independently.

Some businesses are further cementing supplier relationships by providing financial aid and other assistance to unstable supply partners. They may, for instance, assesses key suppliers’ ability to withstand financial shocks and offer short-term financial loans, provide an understanding of what is fueling cash burn, and help improve net return on production.

It goes without saying that this level of visibility and collaboration requires a high level of trust, as well as more open sharing of strategic and tactical information. Companies must ensure that sufficient focus and trust are in place before they begin to deepen supplier relationships because without it, even the best governance agreements and tools won’t yield the desired results.

It may be necessary to establish supply chain risk management programs that require open access to key suppliers’ facilities and business practices. Segmenting suppliers into various strategic categories and establishing new, tailored supply chain management programs is becoming the new norm. The generated transparency is essential to anticipate deficient products or workplace conditions that may result in negative publicity, revenue loss and customer dissatisfaction for the company.

Many leading companies are also incorporating codes of conduct and sustainability criteria into supplier contracts. As a result of the Dodd-Frank Act, for example, many manufacturers are working to ensure that the mining of conflict minerals they and their suppliers use were not the result of civilian exploitation in a war-torn region.

Leverage Technology for End-to-End Transparency

Supply chain managers need information fast to quickly respond to volatile business demands. That’s where technology can help.

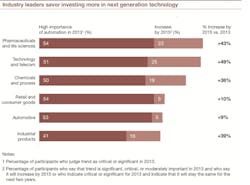

In the past, suppliers often employed disparate applications and data formats, which slowed delivery of information to supply chain managers. Today, however, emerging technology standards enable greater supply chain transparency and data analytics—at a lower cost. This, in part, explains why PwC’s Global Supply Chain Survey found that more than half of respondents said they are implementing or plan to add new tools for better process automation, efficiency and transparency (see chart below).

To harness the power of Big Data, several forward-thinking businesses are collaborating with research universities to explore analytical methods and tools to advance supply chain management. Others are leveraging analytics to develop detailed supply chain models to quantify the impact of fundamental operational changes.

As cloud computing becomes mainstream, many businesses are embracing the technology to take advantage of flexible, scalable platforms for data sharing. Increasingly, supply chain leaders are using the cloud to manage orders, shipments and inventory across the entire supply chain, eliminating delays and improving service.

Taking the First Steps toward Flexibility

Any manager seeking to create a more flexible supply chain will have a full agenda. It will be necessary to integrate strategy, processes, metrics and technology—across the business and among suppliers.

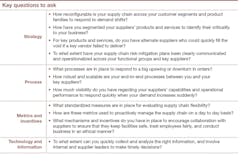

A holistic approach to supply chain flexibility involves a tangle of questions that must be asked of internal stakeholders as well as key suppliers (see table below for some of the issues supply chain managers may face).

Above all, the manager must identify ways that supply chain flexibility can be assimilated into the business culture. Doing so will require that the company can elastically respond to demand shifts, build collaborative relationships with suppliers, and collect and analyze data for timely and accurate inventory decisions. Supply chain managers must also assess the capabilities and flexibility of key suppliers, and ensure that these strategic partners are in sound financial health.

In the rough and tumble of today’s competitive—and still uncertain—business environment, an agile, responsive supply chain is a necessity. It enables companies to effectively work with suppliers and efficiently serve customers, no matter the market conditions.