The church reformer Martin Luther was known for asking a signature question in his catechism: “Was ist das?” In German, literally, “What is that?” but rendered for our English-speaking ears, we would translate it as “What does this mean?”

That’s an excellent question and one that a purchasing professional should be asking any time they receive a quote from a supplier or a cost analysis from their Product Cost Management team. Sadly, however, many times, purchasing professionals don’t even vocalize this question to themselves, much less to their analytics teams, even after the analysis is presented. Instead, they just feel uneasy and uncertain about the validity of the cost analysis. This is a dangerous position, because once the supplier smells that lack of confidence in a negotiation, it’s all over.

Savvier purchasing professionals will ask “What does this mean?” or, more precisely, “What assumptions went into this analysis?” but only after the analysis is done. That’s a better way, but still results in an imprecise understanding of the meaning of the analysis and, often, unnecessary rework.

What is actually needed is a careful design of the cost analysis before any modeling is ever done. That starts with the assumptions that go into the models. At this point in the article, you may be having the same reaction as many of my clients: “Boring! Can’t we just get on the with the analysis?” I used to give in to this complaint, but after learning the hard way, I now stare at my client partners with steely eyes and firmly reply, “I know you don’t want to talk about this now, but I can 100% guarantee if we don’t, we’ll all regret it later.”

The next objection is typically, “But, there’s hundreds or thousands of assumptions! Can’t the cost analyst just figure this out for me?” That’s a fair point, and why a simple framework for your cost analysis can both help you maintain your sanity and win in supplier negotiations.

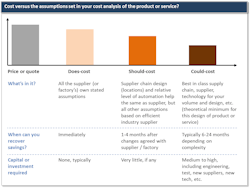

The Does / Should / Could Cost Framework

The figure below shows us an easy way to simplify and improve your cost analytics, resulting in models that will give you confidence to win negotiations. It shows four prices for the product or service you are sourcing, based on four different assumptions sets that go into these prices.

Price or quote

We all know this is: what you’re currently paying or what the supplier wants you to pay. In many ways, it is based on the most complex set of assumptions. That is because it not only contains all the does-cost assumptions but also all the complexities of relationship, market forces, emotions, timing of the business, cost texturing, et. al., “commercial noise.”

Does-cost

A Does-cost is a price calculated from a cost model that uncritically accepts all the supplier’s assumptions (assuming they themselves understood them all and were willing to share them). It would include supplier assumptions for material rates, labor rates, cycle times, overheads, profit margin, etc. The sharp reader will now be asking, “But, then shouldn’t the does-cost EQUAL the price or quote?” It should, dear reader. But, strangely, often even using the supplier’s own numbers you will not be able to get to their quote. Is that a problem? No, there are, at least, two reasons why this is a great opportunity:

- If the supplier’s own assumptions don’t result in the price they gave you, you now have the right to ask for an immediate price reduction and/or clawback. What can they say; the model is based on their own assumptions.

- It will rattle the confidence of your supplier that his own numbers can’t produce his price.

Should-cost

Typically, the term “should-cost” is used to describe an amorphous concept of any estimate, but here we will define it more precisely. A should-cost in our framework consists of a synthesis of two types of assumptions:

- First, we will use does-cost (current supplier) assumptions for the design of the supply chain (e.g. the locations of manufacturing). This will affect shipping costs, labor rates, and sometimes material rates. Second, we will match the the approximate level of automation in the model to the supplier. For example, if the supplier has a horizontal flask casting line, we will assume that in our model, and not a fully automated vertical casting line.

- However, for all other assumptions (e.g. cycle times, material utilization, overheads, etc.) we will assume metrics from an “efficient” manufacture. In this case “efficient” does not necessarily mean a cherrypicked best-in-class assumption for everything. Instead, think of this as a 75%+ percentile supplier who is “among the leaders”

If you only have time to make a cost model with one setup of assumptions, should-cost will usually be the best value for your team’s time. This is because it is the more “realistic,” both for what should be happening at the supplier, and because changes you identify are realizable in the short term. That is, when you discover the difference between your assumptions and the supplier’s inefficiencies, they will not typically require large capital or changing suppliers or technologies to realize savings. Most changes can be implemented in a couple of months.

Could-cost

The is what the product “could” cost, if you and the supplier were willing to invest in the right technology, the best supply chain, etc. where the total cost of acquisition (TCA) is minimized. Think of a situation like the vertically integrated Ford Rouge plant that was optimized to make a specific product.

Note: Could-cost also does not connote cherrypicked best-in-class assumptions for everything. For example, if the minimized TCA was a product made in China, it might have a labor cost that was closer to BIC, but the shipping would not be BIC if delivered to the US. BIC shipping would come from a domestic supplier. Assuming BIC assumptions that are irrational will destroy your credibility with your supplier partners, and are a quick path to poor negotiation outcomes.

Could-cost is the theorical minimum TCA for the current design of the service or product and the current technology available. However, typically a could-cost requires meaningful resources to achieve, for example, new processes, re-testing for quality, new supplier development, etc.

So, which cost assumption set should you use to affect what outcome? That’s a complex question that we’ll cover in our next article.

Eric Arno Hiller is the managing partner of Hiller Associates, a consulting firm specializing in Product Cost Management (PCM), should-cost, design-to-value and software product management. He is a former McKinsey & Company engagement manager and operations expert. Before McKinsey, Hiller was the co-founder and founding CEO of two high technology start-ups: aPriori (a PCM software platform) and TADA.today. Before aPriori & TADA, he worked in product development and manufacturing at Ford Motor Co., John Deere, and Procter & Gamble. Hiller is the author of the PCM blog www.ProductProfitAndRisk.com. He holds an MBA from the Harvard Business School and a master’s and bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

About the Author

Eric Arno Hiller

Managing Partner

Eric Arno Hiller is the managing partner of Hiller Associates, a consulting firm specializing in Product Cost Management (PCM), should-cost, design-to-value and software product management. He is a former McKinsey & Company engagement manager and operations expert. Before McKinsey, Hiller was the co-founder and founding CEO of two high technology start-ups: aPriori (a PCM software platform) and TADA.today. Before aPriori & TADA, he worked in product development and manufacturing at Ford Motor Co., John Deere, and Procter & Gamble. Hiller is the author of the PCM blog www.ProductProfitAndRisk.com. He holds an MBA from the Harvard Business School and a master’s and bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.