Better Supply Chain Management Could Jumpstart Auto Industry

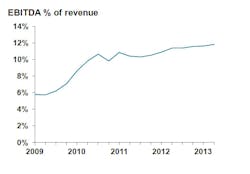

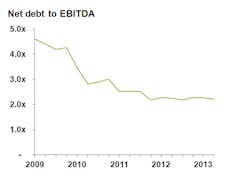

The U.S. automotive industry has experienced significant growth since the 2008-2009 economic downturn, with U.S. automotive sales volumes increasing from approximately 10 million units in 2009, to approximately 15.6 million units in 2013, according to LMC Automotive. Recent automotive financial metrics have also shown similar improvement in profitability and debt ratios throughout the automotive supply base (source: KPMG Vontik database).

However, while the automotive community is optimistic, new challenges are emerging. One of the more common issues currently impacting the automotive supply base is keeping up with the increased volumes, which has resulted in supply shortages. This issue is further impacted by capacity loss and employee knowledge that was removed from the industry during the downturn. Within a short period of time, industry leaders witnessed a shift from suppliers starving for volume with automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) having their choice of suppliers and price, to having leverage return back to the supply base.

Further compounding the volume ramp-up is the dramatic increase in new vehicle launches that automotive OEMs will be undertaking over the next several years to bring fresh product to market. The magnitude of new/major redesign model launches is significant, with North American OEMs alone forecasting 42 production launches in 2014 related to new entry or redesigns. From 2014-2017, the average is 32 per year, compared with 18 per year between 2010-2013, according to LMC Automotive (numbers represent new entry models, and all new and major model redesign).

This elevated launch activity results in significant additional strain being placed on both the OEM and supply base to execute a flawless launch, but still maintain production in an increased volume environment. Further, as automotive OEMs continue migrating to global platforms and global expansion, the supply chain is becoming increasingly complex. This is especially apparent as OEMs grapple with the benefits of global design and scale balanced against cost savings targets and local market demands. This often leads to decisions on sourcing with large, multinational suppliers versus local regional suppliers—all of which impacts the risk profile.

Managing Supply Chain Disruptions

Given current automotive industry dynamics, it is not surprising that supply chain management and efficiency remains a top concern for global manufacturers, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Manufacturing Outlook, sponsored by KPMG International, which was conducted in November 2012. Twenty-six percent of respondents stated that supply chain risk, reliability and flexibility, collectively, are one of their business’ top major challenges over the next 12 to 24 months.

Additionally, participants in the Global Manufacturing Outlook identified four top challenges overall facing their supply chains:

Aligning Operations to Real-time Fluctuations in Customer Demand

There is a trend among companies seeking to increase collaboration with supply chain partners to proactively address demand changes. Many are seeking to implement a “demand-driven supply chain” model, which focuses on better alignment of their planning, procurement and replenishment processes to actual consumption and demand changes to:

- reduce operating expenses;

- act on real-time demand insights;

- identify potential inventory shortages or overages; and

- improve sales performance and customer satisfaction.

The greatest challenge for adopting this model may be more philosophical, given the historical industry practice of guarding information due to lack of trust between supply chain partners.

As collaboration efforts improve and the pace of business increases, it is anticipated that there will be a continued movement and interest in demand-driven supply chain models. Further, once these models are proven effective, increased participation will follow.

Understating Potential Risk and Resiliency in the Supply Chain

There is heightened awareness throughout organizations of understating potential risk and resiliency in the supply chain. In fact, there are new technology solutions being developed to assist with the monitoring of the supply base from a diverse set of criteria.

Often lacking is a complete, 360-degree view of supply risk versus a focus on one element, such as financial performance, quality, or delivery metrics. Further, there are frequently separate departments tracking their own supplier metrics, not linking data signals together.

One key component to developing a leading supply risk process is to compile the most critical internal data into one system with external factors such as country risks, currency risks and regulatory risks, providing a complete supplier risk profile. While it is not practical to identify and mitigate every potential risk, being armed with data and having a process in place to address the most likely and significant risk elements is a leading industry practice.

Under certain circumstances a company may consciously determine there are no cost-effective or feasible options to mitigate certain supply risk. This may be the right solution from a business standpoint, with the key understanding that the risk is present; however, being caught surprised or unaware is unacceptable in today’s global business environment.

While focusing on risk mitigation within the supply chain is critical, supply chain resiliency—the time and process to recover from a supply chain disruption—is also important.

Ensuring Sufficient Supplier Capacity to Meet Demand

Sending representatives to the supplier site to perform a detailed analysis of capacity and product launch readiness, while working collaboratively with suppliers on solutions, is now common practice. It is imperative that site visits focus on detailed capacity studies and seek to understand various aspects of the supplier operation, including other customer demands; future business requirements; sufficiency of capital/equipment; labor force; and supply chain management. It is likely that if the industry were to move more toward the demand-driven model, this would also create more visibility and allow for quicker reaction to capacity issues in the supply chain.

The automotive industry’s focus on increasing sales volume has caused struggles within the supply chain as it tries to keep up with demand in certain segments. This is exacerbated by the fact that it is imperative to understand capacity throughout the tiers of the supply chain to ensure a true picture of capacity constraints. Since capacity issues can have a multitude of consequences such as loss of revenue, unhappy customers and delay in speed-to-market, automotive OEMs are taking action to ensure they have sufficient information to understand and react to their supply base capacity needs and demands.

Overcoming Lack of Information and Material Visibility Across the Extended Supply Chain

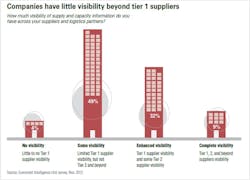

The Global Manufacturing Outlook also noted that most companies have little visibility beyond their Tier 1 suppliers. In fact, the largest proportion of respondents indicated having limited Tier 1 supplier visibility, and no visibility into the Tier 2 level and beyond.

This lack of visibility into the supply chain makes it more challenging to reduce risk, which can result in increased cost and inefficiencies within the supply chain. As supply chains and operations continue to expand beyond the U.S., supply chain visibility becomes increasingly challenging but potentially more critical to understand. Furthermore, as evidenced by several natural disaster incidents, without visibility, it becomes increasingly difficult to assess the impact and/or recover from unplanned disruptions.

This is highlighted by one of the more memorable automotive supply chain interruptions in recent history: the March 2011 earthquake and ensuing tsunami in Japan, which caused significant disruptions, including the shutdown of a Japanese supplier that was the only global producer of a pigment used in paint. It also caused certain major automotive OEMs to restrict the specific color of vehicles for a period of time.

A lack of understanding of other cultures, business practices and distant locales has often led to public embarrassment, regulatory issues, fines and other actions as U.S.-based entities expand globally. One example of regulatory impact on supply chain participants within the U.S. are the Dodd-Frank Act’s conflict mineral rules, which mandate SEC registrants to disclose the use of certain metals derived from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) anywhere within its supply chain in financial statements. Regulations like this have led companies to spend time and resources developing and documenting a process to understand sourcing of components throughout its supply chain.

New Challenges Within the Supply Chain

While the automotive industry has rebounded from the depths of 2008-2009, new challenges have emerged within the supply chain. Instead of production risk being linked to the financial health of the supply base, focus has shifted to a more comprehensive supplier risk assessment model encompassing financial, operational and external data. Further, companies within the automotive industry are continuing to expend resources to understand supplier capacity and improve collaboration and visibility throughout the supply chain.

While these are clearly complex issues to address and solve, it creates an opportunity for savvy automotive companies to undertake such initiatives in an effort to gain a competitive advantage over peers who may be resting on their laurels and viewing the increasing volume as positive reinforcement for future success.

Vincent Pavlak, CPA, is a partner in KPMG LLP’s Transactions & Restructuring service group. Based in Detroit, he has 20 years of experience leading supply chain advisory projects. He has deep experience within the manufacturing and automotive sector.

KPMG LLP’s Aaron Racey, director, Transactions & Restructuring, and Jack Williams, manager, Transactions & Restructuring, also contributed to this article.