“Forget it!” said Sam, shaking his head slowly. “That won’t work here, not with my people.”

I’d just been introduced by Joanne, an executive from headquarters, to Sam, a plant manager at a factory producing ceramic substrates for an electronic component used by an automobile company. He’d announced that I was to help Sam implement statistical process control, or SPC. Sam was dubious.

“Our production quotas are too tight to waste time with some theoretical technique. Besides, my process engineers are tapped out with the new contract.”

“Sam” I said, “I can get started without the process engineers. Let me prove this approach with one of your existing processes.”

Sam paused, looking skeptical. Then a look of inspiration appeared on his face. His office was in a corner with a window overlooking the production area. He pointed out the window at a machine that was running. “Ok,” he said, “start right there at that machine. Show me how this approach of yours can help us there. The parts from that machine are constantly rejected by the customer for one thing or another. Not only that, we almost never meet our production goals. The operator’s name is Ken, but everybody calls him Ken, the Grithead. Go introduce yourself and let me know how it goes at the end of the day.” Curiously, Sam was grinning widely as I left the office and headed for the shop floor.

Ken was a giant of a man, in his late 20s, with shoulder-length brown hair held by a red bandana headband. His job was dirty and his clothes were covered with the slurry that splashed out of the machine. He eyed me suspiciously as I approached. When there was a break in production I stuck out my hand and introduced myself. “What can I do for you,” said Ken, shaking my hand. I explained who I was and why I was there. “I’d like to have you record your usual measurements so we can plot them on a control chart.” I explained. “These are charts that signal when something caused the process to change so it can be fixed right away.”

Ken frowned, then shook his head. “When my boss stops by he’ll ask me how many parts I made, not how much paper I pushed.” He turned and returned to loading his machine. “Would you mind if I hung around here a bit?” I asked. Ken shrugged. Good enough for me.

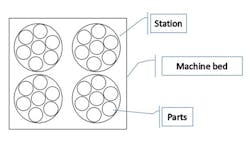

Ken’s machine was a grinding machine (see illustration.) The machine had four stations and each station ground seven parts. The part thickness was critical. Ken was required to check one part from each station for each batch.

I watched which part Ken selected in his sample and made a note of each measurement and which station the part came from. Ken ran about four batches per hour. I also noted any time Ken made an adjustment, added grit to the slurry, or made any other change. Ken pretended that I wasn’t there. This went on until lunch time. Finally, Ken acknowledged my existence.

“What do you have?” He asked, looking over my shoulder. I had the data plotted in sequence and I’d calculated tentative control limits which were drawn on the control chart. I’d marked the head from which each measurement came as well. I’d also marked where Ken made an adjustment or had done something else. Ken looked at the data for several minutes.

“This is when I changed from Acme brand grit to SuperGrit,” Ken said, pointing. “The thickness went down a little after that.” I nodded my head. “It’s only one sample,” I cautioned, “But you might have something.”

“What happened here?” He asked, pointing to an out-of-control point on the chart.

“You turned that dial,” I said, pointing to the adjustment dial. “I don’t know what that dial does, but it made the thickness jump. You turned it back after the next batch and the readings dropped back down.”

“Yeah, I did that because the thickness was getting close to the upper spec. and I didn’t want it to go out of spec.. But the next batch was much lower, so I set it back.”

“Right, “ I said, “the control chart shows that the process was stable when you made the change, so you didn’t really need to make the adjustment. Chances are that the process is barely able to meet the specs.. Adjusting the process when it’s stable will just make it vary more, so things get worse instead of better. The solution is to figure out how to make it more consistent to begin with.”

Ken nodded. “I think that this afternoon I’ll try staying with one brand of grit. That should help some. I’ll use one brand until I run out, then I’ll use another brand and adjust the setup. That should make it more consistent in the long run.”

Ken studied the chart a bit longer. “Say,” he said, “there’s no point in you hanging around here all afternoon. I can plot this chart easily enough. Why not take off and come back later to check what I’ve done?”

At the end of the day I returned to Ken’s machine, along with Sam. Ken eagerly showed Sam the chart, which showed a steady reduction in variation over the day. Ken explained how he’d used the chart to help him identify several ways to make the process better. Sam was floored at the transformation in Ken, but I’d seen similar transformations many times before.

When SPC is used to help people understand and improve their work, instead of just to decorate the walls, it is not just tolerated, it is welcomed.

A version of this article was published in Quality Digest.

Thomas Pyzdek is the President of The Pyzdek Institute LLC. He has written over 50 works, including such classics as The Six Sigma Handbook, The Quality Engineering Handbook and The Handbook for Quality Management. His works have been studied by many in their preparation for various certification exams. Pyzdek is a skilled trainer and a continuous improvement consultant who has worked with many organizations to implement continuous improvement and Lean Six Sigma. Pyzdek is a Fellow of ASQ and recipient of the ASQ Edward’s Medal and the Simon Collier Quality Award, both for outstanding contributions to the field of quality management, and the ASQ E.L. Grant Medal for outstanding contributions to Quality Education.