Are You Caught in the Cost-Cutting Death Spiral?

Have you experienced the dark, painful days of spending freezes and cost cutting? If you have spent any time in manufacturing, the answer is probably yes (My stomach hurts just thinking about how much I hated going into work during those days).

Layoffs, travel bans, no spending without mountains of paperwork, and squeezing suppliers for severe price reductions are just some of the tools used to quickly bring costs down. Good workers (those who can easily find a job somewhere else), routinely leave to avoid these gloomy times and since there is probably a hiring freeze, it is difficult to replace them.

If the company is having severe financial difficulties, then dramatic cost cutting might be understandable (There is the question of how management allowed the company to get in such bad financial shape, but that is for another day). However, there are times when the company seems to be thriving and management still plays the cost cutting card. “If we are doing so well, why do we feel so bad?” is a common thought. How does this happen?

The example below may shed some light on why cost cutting happens in good times and how dangerous this can be for the long-term viability of the business.

Doug was having a good day. In fact, he was having a good month. Things were finally falling into place. The company decided to replace the operations manager, and management brought in someone who believed in teamwork and empowering the employees. Instead of Doug trying to sell him on the need to do lean and Six Sigma, the new operations manager asked Doug to put a plan together to proactively drive improvement throughout the organization. Training was scheduled for next month and the first improvement team launch was scheduled to take place soon after. Doug could hardly wait.

“Hey Doug,” said Mary as she walked into his cubicle. “Big Santa is starting to act up again. Do you have time this afternoon to meet with me and my operators to discuss what we can do to keep that big press running?”

“Sure,” said Doug. “Oh, and by the way, congratulations on your latest promotion. Mary Jones, production line manager… has a nice ring to it. You have come a long way from your days working on the assembly line.”

“Yeah, thanks,” stammered Mary showing some embarrassment. “I have been meaning to ask. Why do they call the press ‘Big Santa’?”

“The shop-floor folks gave it that name,” said Doug. “It runs so poorly at times that in the morning when the operators start it up, they wish for the gift of a day without breakdowns. ‘Big Santa, please give me the gift of a pain free day,’ they would say. So, the name stuck.”

Doug’s boss, Scott, walked into the cubicle and in a heartbeat, it was obvious that he came with bad news. “I need to see you, Doug, and you might as well join us, Mary, since your department will be impacted also. Let’s go into the conference room so we can discuss this in private.”

Mandatory Spending Cuts

“What’s going on?” Mary whispered to Doug as they followed Scott down the aisle.

“I don’t know,” said Doug. “It can’t be good though. Scott looked like he had been run over by a bus.”

“Come on in and close the door,” Scott said as the three of them settled into the conference room chairs. “In the past hour, I have gotten a flurry of e-mails from the corporate folks. As of this moment, we are under a mandatory spending lockdown.”

“NO!” said Doug as the blood drained from his face. “You can’t be serious! Our orders are higher than ever and our backlog grows every day. The company has to be rolling in dough. Why… why… why?” gasped Doug as he buried his face in his hands.

“I don’t understand,” said Mary as she looked at the impact the news had on her friend. “What does a ‘mandatory spending lockdown’ mean exactly?”

“This is the fourth one of these Doug and I have been through over the past 10 years,” said Scott. “The next several months can be quite painful as we are challenged to look for ways to cut our spending to the bare minimum.”

“The recovery period after the spending cuts can be just as painful,” mumbled Doug as the shock of the news was still registering. “Wait a minute! What about the training we have scheduled for next month and the launch of the new improvement teams?”

Doug’s boss just shook his head and the meaning was clear. No training. No team meetings.

“Hmm…” thought Mary. “Does this mean I will not be able to fill the four open positions I have on the production line?”

“Afraid so,” said Scott. “In fact, you will probably be asked to lay off a few people as well.”

“We can’t keep up with the orders we have now,” exclaimed Mary. “I don’t understand. Won’t the spending cuts make this problem worse?”

“That is part of the pain,” said Doug. “Get ready to work a ton of overtime and don’t plan on seeing your friends or family anytime soon.”

“We might be able to convince the corporate folks to give us some relief, but every cent has to be justified,” said Scott. “And, since they don’t believe our capacity numbers, it can be a difficult sell.”

The three of them sat in the conference room for a few moments in silence as the gravity of the situation sank in.

All of a sudden, Mary jumped up, grabbed a pen, and started drawing on the white board.

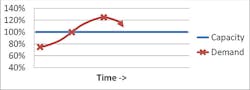

“Remember the lecture we attended a few months ago about the Demand/Capacity Curve? I think this will help explain what is going on around here. Unfortunately, we don’t really know where our bottleneck is or what our maximum capacity line would be. But we do know that the backlog is growing which would indicate that our sales orders are well above our maximum capacity.”

“Our on-time delivery percentage is also dropping as the amount of time it takes to ship a complete order increases,” added Doug.

“Right… So, that would indicate we are at the top of one of the Demand/Capacity peaks,” said Mary.

“Our customers are definitely upset with us,” said Scott. “I get calls every day from angry buyers wanting us to expedite their orders. Some are even threatening to charge us late fees or worse, cancel their orders. However, according to the diagram, new orders should start to fall as customers become more frustrated with our performance, but I have not seen any evidence of this. In fact, orders are as strong as ever.”

“So, what do you think the sales folks are doing to keep orders up?” asked Doug.

“I have a friend in sales. Let’s give him a call and find out,” said Scott.

He turned on the speaker phone and dialed his friend. They got a recorded message. “Thank you for calling. Unfortunately, I am not in to take your phone call. Before you leave a message, let me tell you about the sale we are holding. If you order now, you may be eligible for a 30% price reduction!”

“What!” exclaimed Mary. “We can’t keep up with current orders and they are running a sale?”

“Well, now we know why orders have not come down,” said Doug. “I bet the corporate bosses are putting the pressure on them to not allow orders to drop so they can meet their objectives.”

“Ahhh,” said Scott as a light bulb went on. “And if they are charging less for the product, costs need to be cut in order to hit the profit targets.”

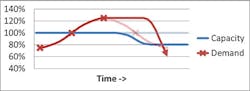

Doug went up to the white board to change Mary’s drawing. “Since we will not be allowed to buy spare parts, replace broken tools, fill open jobs, and our supply chain will hate us after we severely squeeze them on price, we have to assume capacity will take a hit. The gap between the demand line and the capacity line will continue to grow which means all of our delivery metrics will continue to get worse. Our customers will soon hate us even more than they do now, and sales will eventually collapse.”

“This explains a lot,” said Mary with a worried look. “It seems that we are working in a house of cards that is about to come crashing down.”

“Wow… and I started this day with so much optimism,” said Doug with a sigh. “Maybe it is time to update my résumé.”

Do you know where the bottleneck is in your company’s process? Does the bottleneck change from day to day? What is the capacity of the bottleneck?

If your team struggles to answer these questions, then don’t be surprised when your company unknowingly begins down the cost-cutting death spiral. This is one of the critical reasons why lean and Six Sigma needs to be a way of life in all companies.

But it goes deeper than this. Does the rest of the company know what the capacity is and believe the number? There is usually a belief within the other departments that manufacturing hedges its capacity in order to give themselves room for unreasonable demands. “We can only make 10 widgets an hour, but I will heroically drive the team and we will make 14 widgets an hour.”

If this happens, then there will be no trust between the departments. So, just like ‘crying wolf,’ the next time manufacturing says the capacity is “X,” everyone will think it is “X+Y” where “Y” is the amount of capacity that manufacturing is holding back.

The answer is to first stabilize the processes by eliminating unplanned downtime, using statistical process control to monitor key process parameters, and by redesigning product and processes in order to reduce errors. Next, try to make processes as visible as possible so bottlenecks become obvious to all employees.

Once these steps are done, a believable capacity number can be agreed upon. At this point a solid sales and operations planning (S&OP) process can be implemented and the company leaders can compare sales trends with the capacity constraint to help justify the costs associated with busting the bottleneck.

There may be times when demand jumps unexpectedly (competitor goes out of business, a new market opens, etc.) and if the leadership team is on the same page, they can work together to design a business plan to take advantage of the new demand by strategically adding additional capacity as needed.

In addition to manufacturing, these concepts apply to other types of businesses and processes as well. For example, several months ago, the CEO of Panera Bread, Ron Shaich, realized that his restaurants had a great menu, full of tasty, healthy choices. This was driving high demand. However, the customer experience was being negatively impacted by long waits at the order taking stations (the bottleneck).

Fortunately, Mr. Shaich and his leadership team realized that something had to be done and they invested in Panera Bread 2.0. This involves using technology such as touchscreen kiosks and call-ahead ordering to try and increase the capacity at their bottleneck.

If they had not acted, sales could have dropped, profit targets could have been missed, funds could have dried up, and they may have had to resort to cost cutting in order to survive. (If this had led to order takers being laid off, the problem could have gotten significantly worse and they would have spiraled down the cost cutting death spiral.)

This is a never ending journey. Once the order taking bottleneck has been broken, the Panera Bread team will need to search for and deal with the next constraint if they want to continue to grow same store sales.

So, if the company is not willing to work together to manage the Demand/Capacity curve, be prepared to live through months of painful cost cutting every so often. For those of you implementing lean and Six Sigma, know that if done correctly, the constraints will be easier to manage since the processes will be more stable and predictable. If there is broad understanding of the relationship between demand and capacity and all of the functions work together to manage expectations, your company might have a chance to avoid the cost cutting death spiral and those dark, painful days will become a distant nightmare.

John Dyer is president of the JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 28 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. Dyer can be reached at (704)658-0049 and [email protected]. Linked In Profile: http://www.linkedin.com/pub/john-dyer/0/646/75a/ He is on Twitter: @JohnDyerPI.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.