Single Part or Multiple Part Operations: What’s Best for Your Company?

Manufacturing managers concerned about their operation’s performance and overall equipment effectiveness often ask us how their machine and fixturing investments should affect the number of parts that are loaded onto each machine’s work table. For example, if they observe that an operator only has one or two pieces loaded onto a pallet, they may (incorrectly) perceive that both productivity and OEE are suffering.

The optimal manufacturing setup for each product line – in other words, what drives the case for single part operations versus multiple part, or gang operations – depends on many factors. In isolation, the strict application of operation cycle time won’t get you there. You may finish a part on one machine 30 seconds sooner, but if it sits 30 seconds longer in queue before the next operation, there’s no benefit. You may create local efficiencies on one or two machines, but if you’re not looking at systemic delays across the entire process, those spot time reductions will disappear.

Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) has three elements: equipment availability, part quality, and performance efficiency. The key element is performance efficiency. This does not mean that multiple parts processed on one operation necessarily equals more efficiency. Rather, under the right circumstances, a multiple part operation can remove set-up, extra cuts and any maintenance related slow-downs from the operating time.

Getting Started

To arrive at the best set up for your operation, independently evaluate each value stream (product line). The lean approach is all about making parts flow to meet takt time, or customer demand requirements.

When designing a process for multiple part loads, make sure that all operations in that process are able to process multiple parts. Otherwise there is little to no net gain, from a value stream perspective, to have one operation produce 20 parts at a time only to have subsequent processes complete one part at a time.

While there may be some benefit to multiple part loads for smaller parts, gang-type operations tend to lead to batch flow, building up in front of downstream processes. If it’s a bottleneck operation, and there’s an efficiency in loading multiple parts, and as long as that flow supports downstream process requirements, it’s fine. In high volume machining operations, you will see multiple parts being machined at each operation. As soon as you see the parts are queued for an operation that produces one at a time, you just plug up the process with inventory.

The Right Approach? It’s Often Two Distinct Ones

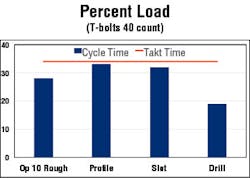

One client’s operation employs both processes. One product line is high-volume hardware parts milled in increments of 40. The parts are milled for a series of characteristics, then re-loaded on a different fixture in a different orientation to the cutting tool, which completes the part. So far, so good.

At the other end of the spectrum, the company also produces a high volume, complex part that’s milled gang style. Four parts are milled in the first operation. Then the second operation mills two parts at a time. The work flow would be okay if the second operation was half the time of the first. Unfortunately, the times were equal, causing a backup of work in process at the second operation.

It got worse. Following those two CNC operations, a series of six manual operations followed, compounding the backup. The six manual operations were fairly equal in machining time, but the operators ran the process in batch mode, further contributing to piles of work in process between operations.

In other instances where the company’s machines accommodate multiple parts, we recommended engineering the process to perform two or three operations in one cycle, employing a fixture for each operation to meet different clamping requirements.

One Flow, Three Operations, Machine and Manual Work

One of this company’s parts required a) machining of an outside profile, b) milling a series of pockets, and c) drilling, then reaming and counter-boring holes.

To make this complex part, the company set up a one-piece flow with three distinct operations that take advantage of machine size and capability, separate the operator from the machine for manual work, and minimize the need for set-ups.

So, What’s Best?

The key concept to remember is it’s all about flow. When multiple parts being machined at one operation at the same time is required for production rates, that rate needs to be maintained throughout the series of operations that produces a complete part. It does no good for large amounts of parts to be machined at one operation, only to sit idle while downstream operations are limited to one at a time, or a reduced number of parts. This only creates bottlenecks and builds up work-in-process inventory.

Daniel Penn Associates, LLC Senior Consultant Tom Voss has developed and implemented lean enterprise solutions for more than 15 years. Trained and mentored in Lean concepts by the founders of Shingijitsu Company, Ltd., his experience spans chemical, industrial, aerospace, automotive and telecommunications industries as well as insurance, banking and public sector services.