Process Management Programs in Manufacturing: Strengths and Weaknesses

At its core business process management is the administrative activities aimed at (1) defining a process, (2) establishing responsibilities, (3) evaluating process performance and (4) identifying opportunities for improvement.

However, even given the straightforward responsibilities of BPM teams, it often feels like there are almost as many variations and models as there are BPM programs.

There are a multitude of factors that shape an organization’s BPM program. Things like the primary purpose of the program, where it reports into, the organization’s structural model, support from leadership, and even corporate culture. However, there are still some core similarities in programs.

To understand the similarities and differences in BPM programs, APQC conducted a survey looking at 'How Process Programs Stack Up.' The survey explored business process management programs’ practices in key areas such as governance, strategy, change, improvement, measurement, tools, and models.

This article explores the findings from the survey and focuses on the strengths and improvement opportunities for manufacturing BPM teams.

BPM Program Strengths

Three common strengths of manufacturing BPM programs include:

- Centralize resources—access to a single source of truth and holistic view.

- Focus on value—support of organizational goals and measures that provide clarity on the team’s impact.

- Create context—provide comparative information on performance and new ways to execute work through benchmarking.

Centralize Resources

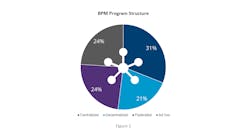

Most manufacturing organizations rely on some form of centralized management (e.g., department or centers of excellence) for their process efforts (Figure 1). While most use a centralized team, almost a quarter use a federated approach that combines centralized governance with process roles embedded in the business. This helps drive adoption and alignment.

Centralized resources (either through a centralized or federated team) provide strategic alignment, governance and accountability, and a consistent communication and implementation plan. In other words, centralization helps the organization deal with many of the challenges associated with change and shifting to a process-focused culture by supplying the following:

» One source of truth—one-stop shop for methodologies, policies, templates, and training.

» Holistic perspective—the ability to tie projects together into a portfolio and look for synergies or overlaps between projects across the organization.

» Top-down, bottom-up monitoring—ability to manage a centralized portfolio of projects provides the ability to look at process efforts across the organization, measure projects’ impacts against organizational goals and programs, and drill into specific projects for root-cause assessments.

For example, Cargill uses a centralized business process consulting group that is a centralized support team, housed in IT, to perform business readiness assessments and continuous improvement work necessary to lead businesses through a successful transformation and sustain cycles of continuous improvement efforts into the future. As part of global IT, the business process consulting resources focus less on technology and more on preparing people and processes for change.

Focus on Value

Supporting the strategic goals of the organization is the No. 1 purpose of most BPM programs (Figure 2). This is followed closely by creating a culture of continuous improvement and documenting processes to understand the how work gets done (i.e., discovery work). Process has traditionally been the team to support driving efficiencies in cost, cycle time and throughput. However, over the past few years process teams are shifting these tactical objectives under broader organizational drivers.

For example, an automotive organization conducted an organizational transformation to move from a cost-driven to a product-driven organization--all of which required a culture shift, empowered employees, and new capabilities. Consequently, the organization used a transformational team that included a BPM group to execute business capability modeling, lean, agile, change management, and design thinking efforts for the transformation.

Additionally, manufacturing BPM teams also leverage their foundational roots in standardization to free up their staff to focus on agility and innovation. By ensuring work is documented and standardized, teams can move quickly because they do not have to spend as much time on documentation and current state assessments during problem solving.

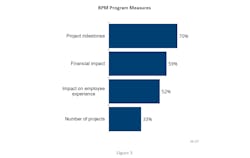

In addition to the purpose of programs, the measures the team uses to track their success indicate their role and unique value they provide the organization (Figure 3). Overall, manufacturing organizations use a mix of impact measures and productivity (project measures). The use of impact measures like financial impact and employee experience are especially vital to show the value that BPM teams bring to the organization’s goals.

Furthermore, these measures align well to the purpose of BPM teams—strategic support and creating a continuous improvement culture. Both purposes tend to include financial- or people- related goals executed through explicit projects.

Create Context

The majority (67%) of manufacturing BPM teams use benchmarking in their process work. Benchmarking processes both externally (with peers or through benchmarking databases) or internally (between teams and business units) helps organizations:

» create an objective foundation for decision making,

» provide context around performance to identify and prioritize improvements, and

» uncover new practices for adoption or adaptation.

For example, Chevron Lubricant’s steering committee for its order-to-cash transformation project leveraged benchmarking to check its performance measures against industry standards during its quarterly check ins.

Opportunities for Improvement

While there are many ways in which manufacturing BPM teams excel, there are also three key areas of opportunity:

- Governance and participation—process roles tend to be tactical and reinforce business silos.

- Process performance management—tend to rely on ad hoc measures, monitoring and manage process in business silos.

- Improvement portfolio—improvement opportunities tend to be ad hoc and managed in silos.

Governance and Participation

Though struggles with process governance has been an ongoing challenge for most organizations, manufacturing BPM teams have made headway in process governance. Over three-fourths of the survey participants leverage process owners, who in turn ensure control and accountability of the processes by the relevant business (Figure 4). Additionally, over half of the participants include process sponsors to support and champion process projects and improvement specialists to execute the work.

However, manufacturing organizations’ governance efforts tend to be tactical, relying on roles focused on a specific process project or in business silos. These roles are typically used as project team members (67%) or to validate or test new or re-engineered processes (61%).

Because of this, most BPM programs are missing out on senior-level strategic roles (e.g., steering committees). These roles are vital and provide oversight and governance for process work, prioritize opportunities, and align processes and process work with organizational strategy and objectives.

Process Performance Management

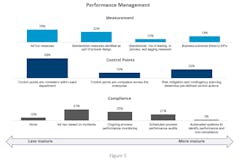

The biggest gap of BPM teams, regardless of industry, is how they manage process performance. Process performance management was assessed using three criteria:

- Measures—the types of measures used and their connection to business value.

- Control points—business activities that are embedded in the process to ensure that the process is executed in a controlled manner and mitigate risks.

- Compliance—audits and ongoing monitoring of process execution.

Measurement is another evergreen challenge for BPM programs (Figure 5). Almost a third of manufacturing teams identify measures as part of their process documentation. But these measures are ad hoc, based on what they’ve always measured, or focus on lagging indicators. Less that 20% of teams connect their processes’ performance to the business outcomes they drive. This in turn means problem solving is reactive and can make it more difficult for BPM teams to illustrate how their work drives organizational value.

Similar to measures, manufacturing teams use of control points are a good start that don’t quite provide the value that they could. Though the majority of manufacturing teams use control points, they are limited to process and business silos and are reactive. Only a quarter of teams have developed risk mitigation or contingency plans for when things go wrong. Additionally, given the tie between control points and measures, until process measures are more strategically determined it’s difficult to control execution effectively.

Finally, the last key element, compliance, assesses how performance is monitored and managed and is where manufacturing teams tend to be more mature. Though over a third of teams conduct compliance monitoring as a reaction to a performance incident, over 40% conduct some form of proactive performance supervision.

Improvement Portfolio

In addition to measures and governance, BPM teams struggle with process improvement, from identifying potential opportunities to prioritizing them for inclusion in a portfolio of projects. The majority (62%) of manufacturing improvement portfolios do not extend beyond business unit borders and just over a fourth use selection criteria for opportunity assessments.

This means teams struggle with ensuring their improvement efforts are balanced, proactive, and focus on the problems that have the highest value and not just which problems are the “loudest.” It also limits their ability to take a holistic perspective when it comes to improvements so that they can take advantage of synergies between projects and develop improvements that won’t fix one area while breaking something further downstream.

The solution is a project portfolio that uses standardized scope and clear selection criteria for assessing the improvement project’s need and fit.

The first step to project entry is defining the project’s scope. This helps create boundaries and ensures that everyone understands what the team is trying to accomplish, the complexity or potential difficulty of the project, and what’s in and what’s out.

To establish the scope of the project the team needs to work with its stakeholders to define:

- What is the business need that the process supports?

- What is the scope of the process you are trying to fix (e.g., process or value stream)?

- What are the inputs that trigger the process?

- What is the intended output of the process?

Once the team has outlined the scope of the potential improvement, they need to use clear criteria that assess things like value, strategic alignment, risk, and impact to determine the type of problem and what is the core need that should be addressed in the improvement project.

Conclusion

Overall, manufacturing BPM teams are constrained by business silos, ad hoc and reactive means to managing processes performance, and lack of standardized criteria for decision making. However, manufacturing BPM teams also exhibit high maturity practices in many key areas. They are focused on value and providing strategic support for their organizations. While they need a broader perspective on portfolio breadth, they are more likely to take a scheduled audit approach for identifying improvement opportunities. Which means they are more likely to spot issues early, rather than reactively. Finally, though they are unlikely to use selection criteria, their use of benchmarking helps create context around process performance for decision making.

Holly Lyke-Ho-Gland is a principal research lead who conducts and publishes APQC research on process management and improvement, quality, project management, measurement, and benchmarking for APQC’s Process and Performance Management research team.

About the Author

Holly Lyke-Ho-Gland

Holly Lyke-Ho-Gland is a principal research lead who conducts and publishes APQC research on process management and improvement, quality, project management, measurement, and benchmarking for APQC’s Process and Performance Management research team. Her research supports APQC members and clients across disciplines and centers on helping professionals and project managers solve business problems with strategy, process and measurement.