Making Sound Decisions on Cap-Ex: A Guide for Early-Stage Companies

American manufacturing is back in the national conversation, but it’s a proposition vastly easier said than done. The challenge is that manufacturing requires physical assets, dictating substantial capital outlay before you earn a dime from them. It’s a risk that’s difficult for businesses of all sizes to address; however, for an early-stage company, overspending will kill your company before it even has a chance.

This article will give financial guidelines for early-stage firms to make sound decisions on capex spending. And as it turns out, the type of product you make has a huge impact on your strategy.

There are two important aspects of capital spending: how much you can spend, and how much you should spend. How much you can spend comes down to financing. Early-stage companies need to consider how much they can raise from markets, and how much of that to allocate towards capex versus other aspects of their business, like salaries. It’s a short-term play. How much you should spend comes down to ensuring your product is competitive in the marketplace, a long-term play. In addition to impacting product quality and revenue, your capex spending will affect your pricing structure for years to come.

Let’s first consider how much you can spend on capex. It’s limited by how much money you can raise. Part of this is equity, and part of this is debt. We looked at Pitchbook data for a variety of manufacturing sectors as a starting point for our analysis, to determine the equity side of the equation. The median deal size by industry sector, in 2023, is shown in Table 1.

You can see large differences among sectors, especially at advanced company stages.

- For the Seed stage, the median deal size ranged between $1-5M.

- For Series A, some differences emerge. The median size for Utilities, Food & Beverage, Household Goods and Agriculture was $3-7M. The median size for Utilities, Automotive, Chemicals and Industrial Machinery was ~ $10M, and Steel was larger, at $28M.

- For Series B, notable differences are observed. No deals were reported for Household Goods, Utilities has a median value of $40M and Iron and Steel has a median Series B value of $877, while other industries have median deal sizes between $14-22M.

- For Iron and Steel Mining, no Series C rounds were reported.

So what does it mean in terms of how much you can spend? First, companies in the Household Goods and Food & Beverage sectors should aggressively seek strategies that minimize capex spending. In general, they raise the least amount of equity, so they need to consider asset light business models, either producing with contract manufacturers or leased assets. Companies in the Utilities and Iron and Steel Mining consistently attract more funding. This gives them the greatest flexibility to deploy capital towards capex. But looking at the data, it’s not enough to stand up a manufacturing business alone.

Viewing the median-sized deal as the most likely scenario for fundraising, then it is clear equity financing alone is not sufficient to build a greenfield, first-of-a-kind (FOAK) facility. These facilities typically begin at $20M for a pilot facility, and full-scale facilities cost more than $100M. Even the steel sector, with a median Series B deal size of $877M, cannot cover the costs for a new steel mill, estimated at $3B. Furthermore, equity is needed to finance the operating expenses at a firm, such as salaries, working capital and leases.

What about debt? Companies often look to venture debt or equipment financing to help plug the gap. What we see as investors is that venture debt is typically limited to a fraction of an equity raise, typically up to 30%. And equipment financing is limited to the value of the equipment. Both can be effective strategies of extending equity, but not enough to fund a new facility. Additional debt structures, such as project financing or loans from banks, are available once you’ve established contracts or revenue and can get guaranteed pricing on facility construction. This isn’t typically an option for early-stage companies, building a FOAK facility.

What does this mean? For initial stages of production, companies must focus on purchasing just the key assets that cannot be found elsewhere. For Household Goods and Food & Beverage, there are very few exceptions to this rule. For other industries, there are exceptions, especially for Iron and Steel Milling. If you think you fit the exception, be crystal-clear with investors on why it is necessary, and be sure to build a compelling case.

With this approach, early-stage companies may be able to spend up to $5M on capex, increasing in later rounds. This should be sufficient to add parts of a manufacturing line, or even an entire line, so that they can manufacture their product. However, the capex spending must be sufficiently sized to production, so that its capital depreciation does not excessively burden production.

If you feel it’s absolutely necessary to build your own facility, fundraising has to be a top priority. This may be the case if you’re building a First-Of-A-Kind (FOAK) facility. In addition to equity, we’ve also seen some companies leverage the public funding system to unlock access to government grants and loans, as well as leverage project financing. But you should be aware that this is more the exception to the rule, and need to make it a key part of your strategy.

Cost of Goods Sold

The story doesn’t stop here. How much you can raise is just about the total you can spend. But how do you decide how much you should spend? It all starts with COGS, or Cost of Goods Sold. Assuming your goal is to compete in an open marketplace, you must sell competitively priced products. To do so, you must make products that have COGS similar to comparable products.

The COGS for any product contains a contribution from the capex spent on assets required to manufacture it. This contribution takes the form of capital depreciation attributed to the COGS. Therefore, you can assess the industry standard for capital depreciation, and then use that as a guideline for your capital spending.

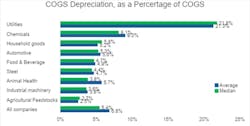

How do you get that information? Well, publicly traded companies that offer competitive products often report their COGS, as well as the depreciation component of their COGS. To determine what may be appropriate for common industry sectors in the climate tech space, depreciation, as a percentage of COGS, was determined for the top 400 publicly traded companies in the U.S. in selected industry sectors, along with 2-4 additional competitors based outside the U.S.

Below are the average and median contributions, to help demonstrate the range of values.

When all companies are included in the analysis, depreciation was 5% of COGS. However, the results vary significantly by sector. Animal Feedstocks has the lowest, at 3%, followed by Industrial Machinery, Animal Health and Steel, at 4%, then Food and Beverage, Automotive, and Household Goods, at 5%. Chemicals is 8%, followed by Utilities, at 21%.

The median for each sector gives a good preliminary approximation for the appropriate amount of depreciation to COGS. However, there are differences in the median and average for all sectors, and likely are a result of different operating and business models. It is especially notable in the Animal Health and Chemicals sectors, with values ranging from 3.1%-11.3%, and 3.9%-15.6%, respectively.

As a more refined approximation to the appropriate contribution of capital depreciation to COGS, your team firms should do further analysis on competitors that sell similar products. Once you firm determine a targeted depreciation for percentage of COGS, they should develop a capex budget that ensures you they do not exceed it.

If you overspend on your capex, it will hurt you in the short term, requiring you to raise more money than you need, and in the long term, it will impair your ability to compete in the marketplace. It’s enough to sink your company.

If you decide to spend money on capex, be convinced that it is imperative to getting your product in the marketplace. And make sure the contribution to your COGS is either inline with the industry, or gives you an advantage on pricing in other ways, so you can continue to compete effectively in the marketplace.

About the Author

Tony Moses

Entrepreneur-in-Residence, At One Ventures

Tony Moses is an entrepreneur-in-residence at At One Ventures, where he helps the firm’s portfolio companies successfully scale-up their climate technologies. He brings manufacturing experience of 23 years in various industries, including pharma (Merck), food and beverage (Conagra Brands) and flavor chemistry (Givaudan) among others, and has a Ph.D. in chemical engineering.