What, Exactly, Is a Leader’s Responsibility Around Psychological Safety?

The other day, a client of ours reached out expressing some confusion—frustration, actually—about the expectation that a team leader needed to create a psychologically safe environment, while some team members were underperforming.

“One of the problems I have with the modern workplace (and in parent-child relationships, for that matter) is that employees often want management to take responsibility for too much,” the client wrote. “Let’s foster safety and candor, sure; but when/where/how are employees accountable for developing mental toughness?”

There is a lot to be frustrated by here. What is the organization's definition of psychological safety? Is the plea for safety a way of avoiding performing? Is safety the sole responsibility of the leader? And so on …

The Limits of Psychological Safety

As many of you will know, the idea of psychological safety was made popular in Google’s study of high-performing teams in 2015. Google’s study is correct. Teams perform better when members are comfortable bringing more of themselves to the workplace—sharing their ideas, even if contradictory. The problem is that complete psychological safety in most organizations is a misnomer if not a fantasy.

In many workplaces today, sharing deep feelings about our identity may actually find us cast out. And while some of us may feel more self-assured than others to speak our mind, can any of us feel wholly safe in a setting where we are expected to perform and produce at a certain level, evaluated and then paid on that performance? Let’s take a deeper look.

Parent, Adult, Child

Interestingly, our client’s articulation of the problem mentioned a parallel to parenting. In psychological terms, one of the important dynamics between team members that is constantly at play is dependency, something we experience growing up. We depend on our parents for nurturing and protecting us as children. The nature of these “attachments”—knowing who we can depend on for what, and how we develop the capacity for self-caring and self-reliance—are critical in adulthood.

In 1957, the psychiatrist Eric Berne presented a paper to the American Group Psychotherapy Association titled “Transactional Analysis: A new and effective method of group therapy.” His

subsequent bestselling book Games People Play (1964, Grove Press), which has sold more than five million copies, offers a helpful framework for understanding an aspect of how we can easily promote or undermine accountability.

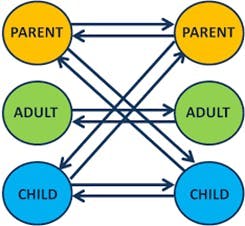

In Berne’s clinical work, he observed that interactions between people reflected one of three “ego-states” that were unconsciously playing out: Parent, Adult, Child. In these interpersonal transactions, how one person acts and communicates has a reciprocal effect on the other.

For example, when one person behaves like a Parent (either nurturing or critical), the other may react as a compliant or rebellious Child, or, perhaps, as an argumentative other Parent. And, if one party acts like a Child, the other may respond as the caring or reprimanding Parent, or go on to “play” as another Child.

These are not productive roles to assume in the workplace. If we want our team members to act like thoughtful, creative and accountable members, they need to be treated as and conduct themselves as Adults.

Structure Makes It Difficult

Among the challenges we all face is that organizations are hierarchical and office dynamics often value the superior-to-subordinate relationship, which fosters dependency and is often engaging in a Parent-Child relationship. We need to facilitate Adult-to-Adult interactions and work extra hard to counteract our tendency to see through a hierarchical lens. If we are honest, we also need to work against the superior status we enjoy if we are the team lead. We need to learn to lead from behind and work against any superior status as a leader. Leading is about people, not about your ego (2018, HBR).

The Need to Speak Up

Unfortunately, psychological safety has taken on a meaning beyond Amy Edmonson’s original use. Her research revealed how people often don’t tell the truth for fear of retribution: a nurse not telling the doctor that the chart or dosage was incorrect, or executives going along with the boss’s decision to acquire a company, knowing it will be a disaster.

Edmonson follows a legacy of research that shows how sharing our honest views is distorted by social pressure.

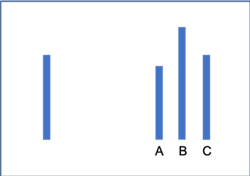

Solomon Asch’s experiment is a favorite. He asks 10 participants to match the length of a line on one side of a diagram with one of the three alternatives on the other. In fact, only one of the 10 participants is being studied. The other nine are stooges who follow Asch’s instructions to give the wrong answer before the participant makes their selection. Sure enough, in repeated attempts, 75% of the time participants yielded to group influence and went along with their incorrect answers.

And Leonard Bickman’s Uniform experiment in 1974 offers an illustration for how leaders will affect team members’ behavior, merely by being seen as an authority figure. In this experiment, three people played different roles: one dressed as a milkman, one as a security guard and one in plain clothes. Each actor approaches passersby on the street and asks them to perform a simple request, such as picking up a piece of litter or giving them a coin for a parking meter.

Passersby complied with the requests from the security guard 80-90% of the time, while only 35% with the other two actors. It’s a good reminder of how we need to counteract the compliance to authority bias that exists in organizational hierarchy, if we want our colleagues to be Adults and speak up.

So How Do We Address Underperformance?

In our view, the leader’s role is to facilitate people feeling free to speak up. It is not the leader’s role to ensure that everyone on the team is completely comfortable, or overly protected from the very real threats of competition, or the challenges associated with performing their roles and responsibilities. Is it the manager’s role to contain anxiety and offer support where needed? Absolutely!

If a team member, or members, are underperforming, we need to empathically address this issue head-on, not avoid it. Ironically, it is the leader who needs to feel “safe” to intervene. We need to be Adults working with Adults who are comfortable surfacing difficult conversations, listening with an open mind, leading with empathy and partnering to find solutions.

In Summary

Do employees want managers to take responsibility for too much these days? We are not sure. The team leader is ultimately responsible for the performance of their group, and that is completely dependent on the performance of the individuals. In this regard, the manager is responsible for setting the context in which those individuals can thrive, including:

- Ensuring the team has the right skills and resources

- Engaging team members as adults

- Creating a work environment that is inclusive of all types, where colleagues feel safe to speak up about the work

- Setting and aligning clear role expectations

- Discussing performance—what is working well and what can be even more effective

It’s important to recognize the limits of the leader’s responsibility. Overstepping may only encourage childish behavior. Having set the context, we must empower, trust, empathize and not overstep. Whether as leaders or parents, one of the hardest things we do is to provide a safe and open environment, while still supporting people to perform as best they can.

Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, Chris Morgan is an experienced and trusted executive coach. He is a partner at Morgan Alexander, and co-founder of Listentool, a real-time feedback software solution.

Marc Maltz is a partner at Hoola-Hoop LLC who brings over 40 years of experience advising for profit and nonprofit executives. Marc spent a number of years as an operating executive, is a limited partner, serves on boards and writes and lectures on organizational psychology. Marc resides in New York City.

About the Author

Chris Morgan

Founder and Principal

Based in the San Francisco Bay area, Chris Morgan is founding principal of Morgan Alexander, a consulting firm that coaches senior management teams to lead winning organizations, and co-founder of ListenTool. He is one of a few executive coaches with more than 20 years of experience, having started with The Alexander Corporation. Morgan’s clients are primarily CXO engagements with Fortune 500 companies, and high-tech startups in the San Francisco Bay area.

Marc Maltz

Partner, Hoola-Hoop LLC

Marc Maltz is a partner at Hoola-Hoop LLC who brings over 40 years of experience advising for profit and nonprofit executives. Marc spent a number of years as an operating executive, is a limited partner, serves on boards and writes and lectures on organizational psychology. Marc resides in New York City.