Does it seem like lean has been under attack recently? For example, several lean proponents were up in arms in the wake of a July article in the Wall Street Journal. The article outlined component shortages faced by Apple and Nissan Motor, and concluded that in part "the drawbacks of lean manufacturing methods" were to blame, augmented by an overstretched global supply chain. Shoddy investigative reporting, commented one lean proponent about the article. Apple has never been considered a lean company, pointed out another. Lean has been completely misconstrued, said yet a third.

Toyota's recent woes, too, have been cited as an example of the failure of lean, a position frequently opposed by those who claim the failure was Toyota's straying from its own Toyota Production System (TPS), the epitome of a lean production system.

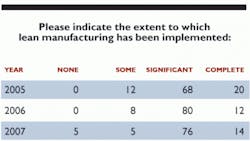

At the other end of the spectrum are the manufacturing companies and plants that extol the great productivity and other operational gains they have reaped through their implementations of lean manufacturing. Indeed, over the past five years more than 90% of finalists and winners of IndustryWeek's own Best Plants competition, which recognizes manufacturing excellence, reported implementing lean manufacturing to a significant degree or more. Those same plants reported median 30% reductions in manufacturing cycle times over the past three years, median scrap reductions of 33% and median productivity improvements of 24%.

Why the diversity of opinions regarding lean? If you speak with lean experts, a possible answer rears its head. That answer is that people are confused -- both about what defines lean as well as how to implement lean. Get that confusion straightened out and the value of lean as a driver of operational excellence grows more apparent.

What is Lean?

What precisely constitutes "lean" has been a challenge for many since the term joined the manufacturing lexicon more than 15 years ago. The term was coined by researchers led by James Womack to describe how Toyota ran its business. On Womack's Lean Enterprise Institute website, lean's core idea is described in this way: "to maximize customer value while minimizing waste. Simply, lean means creating more value for customers with fewer resources." Lean thinking, the explanation continues, "changes the focus of management from optimizing separate technologies, assets, and vertical departments to optimizing the flow of products and services through entire value streams that flow horizontally across technologies, assets, and departments to customers."

In reality, the definition of lean frequently varies depending upon whom you speak with -- whether it should or not. "I have always said if you had 100 lean practitioners in the room and asked for a definition, you might get 80 answers and about 20 themes, mostly around the tools of lean," says Sue Gillman, a partner with Aveus LLC.

Lean is Strategic

Lean is strategic, states Rick Bohan, principal of Chagrin River Consulting. He says that done right, lean should provide an organization with substantial core capabilities that are difficult for other companies to emulate even over the longer term. A sustained competitive advantage is how he describes it. Few lean experts likely would find fault with that description.

That said, managers don't always view lean in that fashion. "They tend to implement [lean] as if it were simply tactical," Bohan says. "They view it as simply a set of cost-cutting tools. Lean means providing better service to the customer at the same or lower cost, and looking at it simply as a set of cost-cutting tactics often can send a company down the wrong road." Unfortunately, there exist literature and even consultants who reinforce that viewpoint, Bohan adds.

The definition of lean is "pretty subjective," agrees lean expert Art Smalley. "The analogy I use is the four blind men and the elephant, and they're all touching a different part of the elephant and they're all trying to tell you the truth of what they're seeing or touching, but it's not the whole." Smalley is among the few Americans who have worked at Toyota in Japan, and he makes a distinction between lean and TPS. He is author or co-author of several books about lean, including "Creating Level Pull" and "Understanding A3 Thinking."

The lack of an agreed-upon definition may play a part in the current state of lean, which Smalley describes as a mixed bag. There are isolated success stories, he says, as well as a few plants that are implementing lean without results. Then, he says, there is a large pack in the middle that have started on the lean path, using a variety of tools and wondering why they're not getting better results. "They're starting to question themselves, which is a good thing," Smalley says.

Lack of a clear definition may impact peoples' perceptions about what lean is. It may contribute to lean implementation outcomes. But execution -- or lack thereof -- is a significant contributor to a lean implementation's success. That's because lean is ultimately about solving problems. "The lean movement has been characterized by a tool-based emphasis," Smalley says. People fall in love with tools like pull systems, 5S and standardized work, for example, and forget to problem-solve. "You really have to put [the tools] in the right structure and context with problem solving discipline to improve productivity, quality, cost, delivery, whatever dimension you are focusing on," he says.

Who is Doing Lean?

Good data to identify how many manufacturers are employing or attempting to employ lean are difficult to come by. Lean guru Norman Bodek suggests that maybe half of U.S. manufacturing companies are into some aspect of lean. "Many do run kaizen blitzes, but only a fraction are truly committed to using all of the aspects of lean," he suggests. "As an example, I feel that only 1% have the person pull the cord' [to] stop the process when they discover a problem." Bodek, an author and publisher, has traveled to Japan more than 50 times to bring Japanese manufacturing methodologies, including the Toyota Production System, to U.S. industry to help improve quality and productivity.

Bodek is leading a week-long lean study tour to Japan in September, which quickly sold out, seeming evidence of lean's continued draw. While that news is good, it's only 24 travelers, points out Bodek. "We should have 24,000 wanting to go," he says.

Thomas & Betts Corp. is among the manufacturing companies that have embraced lean in its operations. Most of the plants use some lean tools every day, says Herb Bradshaw, plant manager at Thomas & Betts' Athens, Tenn., facility, a 2005 IW Best Plants winner. Whether it be from when customers think about purchasing a product, to using pull on the manufacturing floor, to working with suppliers, or to stabilizing processes -- "We use lean in everything we do."

And lean continues to reap dividends for the Athens plant, even as it has been a constant for nearly 10 years. For example, he points to a recent team effort that improved throughput in a cell by 40%. "It never ceases to amaze me." Like others, Bradshaw also shared his belief that an operation never fully implements lean, "because you always see more things to work on."

What's Missing?

Companies' lean implementations frequently focus on singular aspects of the process rather than the whole, suggest several lean experts. For example, Smalley opines that quality is underemphasized. Just-in-time and flow seem to take precedence even though "jidoka" -- or quality built in during the manufacturing process -- is a pillar of equal importance to JIT in the Toyota Production System. Jidoka, which Toyota translates as automation with a human touch, means that equipment stops running when it detects a defect and ultimately when processing is complete.

That ties into another difference between lean and TPS outlined by Smalley -- the production equipment. TPS emphasizes the importance of quality machine tools, with significant emphasis on developing better machines that break down infrequently. That's not so much the case with lean, he opines. People often take the machinery for granted, while they will point out the kanban system or a standardized work chart. The equipment is underappreciated because what is happening is invisible inside the machine, he says. For many people, "You walk by all these big machines, and you don't even know what you're looking at," Smalley says.

At the other extreme is the human side of lean, an aspect Bodek says U.S. companies tend to overlook. Bodek cites automotive industry supplier Autoliv as one example of a manufacturer doing a good job of addressing the human side of lean. Last year at an Ogden, Utah, Autoliv plant, he notes, managers received 63 implemented ideas per person. "They are an excellent example of a lean plant. People are encouraged to use their brains, opposite to the [Frederick] Taylor concept of asking the workers not to think." That's not to say it doesn't still have a ways to go, he adds. Even Toyota, Bodek says, has not designed work for the full potential of its people's talent.

Lean is never successful without substantial involvement from employees at all levels, adds Bohan. In most companies, that requires a substantial culture change, an aspect of lean that Bohan says frequently is ignored. Adds Bodek: "People should be empowered at every level based on their experiences, expertise and knowledge, but our management system asks everyone before change takes place to get permission and that permission is rarely granted. There is a great fear of making mistakes and yet making mistakes is one of the only ways we learn."

Aveus' Gillman cautions that lean gains are not sustainable without employee buy-in and involvement, at least "not if the employee is expected to participate in the new process, or way of doing things, over time."

She adds, "Lean generates a lot of excitement and initial buy-in to the process and solution. However, the test of sustainability is if you can move the people who instituted the change and the process remains robust."

Asking "What's Next" Too Soon

The lean movement continues to grow and evolve, moving beyond manufacturing production and into areas such as product development, administrative, information technology and accounting. It has moved beyond the manufacturing industry as well, most notably into the health care industry.

Smalley suggests that asking what's next for lean is a question that may be posed too soon. He remains focused on today, noting there is still plenty in the here and now to address. "When we have 100% uptime, 100% quality, short lead times, then we can worry about tomorrow," he says. "If you want to get results, you have to address your problems of now."

Related Content: Don't Let Size be a Barrier to Lean

About the Author

Jill Jusko

Bio: Jill Jusko is executive editor for IndustryWeek. She has been writing about manufacturing operations leadership for more than 20 years. Her coverage spotlights companies that are in pursuit of world-class results in quality, productivity, cost and other benchmarks by implementing the latest continuous improvement and lean/Six-Sigma strategies. Jill also coordinates IndustryWeek’s Best Plants Awards Program, which annually salutes the leading manufacturing facilities in North America.

Have a story idea? Send it to [email protected].