Leadership Coaching 3.0: Directing Human Potential

Coaching is one of those words that we use on a daily basis in a business setting with quite different meanings for different people. Often, the first association is to a sports coach who will provide structured training for fitness and skills. Interestingly, the word originates from a horse-drawn carriage or coach. The idea of helping someone get to their chosen destination is still very much at the essence. We are all coaches in one way or another.

In the late 1970s, groups of skiers could be seen imitating eagles, experiencing the exhilarating weightlessness as they floated through the gravity-less fall line while changing from one direction to the other. At the same time, business executives were taking coaching lessons on the tennis courts near New York, Boston and London. Both groups were learning how to tap into the optimal state for performance and learning—"non-judgmental self-awareness” as Tim Gallwey would call it; “flow,” a term coined by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; “mental toughness,” as Jim Loehr would say. These days, we call it “psychological safety” in a business team. A decade ago, we might have referred to it as "trust.”

The Human Potential Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s significantly influenced the rise of the non-directive style of coaching that has become the standard we teach today. The movement was founded on the idea that people possess inherent potential which can be realized through goal-setting and cultivating the right mental state. It challenged the notion of viewing individuals as empty vessels who need to be filled with instruction.

Certainly, this shift improved on the legacy coaching model. However, I believe the pendulum has swung too far, and it’s time for a new coaching framework that reflects what we have learned since then.

Expertise Is Needed

Today, the mainstream of executive coach training advocates an approach independent of expert knowledge and advice.

The International Coaching Federation (ICF) is the most well-recognized training body and the primary source for professional accreditation in the field. However, the list of competencies that they train on are void of advice for the typical challenges a business leader might confront, such as developing a good strategy, managing change, stakeholder relations, dealing with an underperforming team or simply running effective meetings

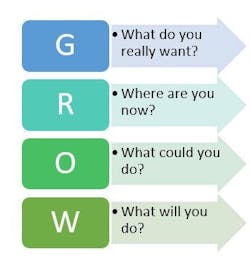

And the most widely used coaching model, GROW (Goal, Reality, Options, Wrap Up) is purely facilitative.

It centers on asking the “coachee” to describe what they want to get from their coaching session (Goal) and to list the possible solutions (Options) they see. The coach is encouraged to hold back from providing advice, fostering an environment where clients can solve problems themselves.

What Are the Benefits?

The rise and popularity of non-directive executive coaching is due to the substantial benefits it brings.

It’s an impressive list, and includes the following:

- It prioritizes the client’s goals, increasing the relevance of and buy-in to the development program.

- By offering confidentiality, it creates a safe space for learning to occur – for the candid conversation about strengths and how we need to be even more effective.

- By encouraging clients to find their own solutions, it puts them in charge, increases their sense of agency and counteracts dependency on the coach. Relatedly, it improves their problem-solving skills.

- It creates a greater ownership of solutions steps and the likelihood of developmental actions being taken.

- It meets the client “where they are at” by listening deeply to their concerns and exploring their perspectives rather than making assumptions that often miss the mark.

- It raises self-awareness both through reflection and often through guided peer feedback.

However, we have learned that a purely non-directive coaching approach has its shortcomings.

First, while empowering clients to discover and “realize” their inherent potential has many benefits, it can, and often does, lead to an unnecessarily long and painful learning path. In fact, it can create an ungrounded psychological “grandiosity” and potential failure.

Many years ago, I asked a partner in Boston Consulting Group’s London office if he thought that their clients could be facilitated through self-reflection to the right conclusions rather than being directed via their firm’s extensive analysis and conclusions. Of course, he said no! The big consulting firms are often criticized for providing too much advice and not enough attention to the psychology of change. On the flip side, I am aware of multi-million-dollar organizational change programs founded on the promise of the right collective mental state that have ended with clients in bankruptcy because the real problem was organizational and not psychological.

Even the more immediate challenges an executive team leader typically faces may not easily be solved intuitively and could benefit from expert suggestions. For example, the non-stop battle of figuring out when to Do, Direct or Delegate a task – or how to structure meetings for high productivity and motivation – or how to hold your team members accountable without pissing them off – or when to coach vs. replace – or how to balance commitments to investors, the board, the team, your family and your health.

Commitment and self-reliance are necessary but too often insufficient to solve the complex challenges business leaders face. An improved coaching framework needs to acknowledge the value of the traditional approach of providing expert advice. Clients will appreciate the guidance and achieve their goals faster.

A second issue with the non-directive coaching style is that its development goals are supposed to be self-determined. Much like seeing a therapist, the question a coach will pose is some form of “What are your goals from this coaching engagement?” and/or “What topics would you like to work on?”

Once again, we should acknowledge the benefits of engaging the client around their interests and empowering self-reflection. However, the reality is often that development goals are driven by the business. Sometimes, certain competencies need to be developed as part of a high-potential program; other times, there may be leadership-style issues to overcome.

In many ways, good executive coaching has already adapted to this challenge by bringing in some of the old directive style via feedback mechanisms that elevate development needs against expected competencies. Feedback is a very powerful learning tool, but giving feedback requires considerable expertise to surface and deliver accurate and useful insight in a way that helps rather than harms. Some coaches resist feedback, not wanting to demotivate their clients or harm the working relationship, while others strongly believe in the benefits of delivering candid and blunt messages. The best-trained coaches realize that getting feedback right is a matter of achieving both the right mental state and delivering the honest facts and advice.

Advising vs. Suggesting

Last month we lost Graham Alexander, one of the executive coaching “greats.” He pioneered the introduction of coaching in Europe, supported countless CEOs and was a mentor and a good friend to me. I once asked him about providing advice within the framework of non-directive coaching, and he lit up with his typical charming enthusiasm in his reply: “Chris,” he said, “I think it’s important to make the distinction between advice and suggestions. I am a big believer in making suggestions.”

If we aim to maximize an individual or a team’s performance, we need a new framework. Coaches should be trained on the human potential model and on solutions for common problems. Without connecting deeply to the client’s interests and providing a safe space for the learning conversation, we risk losing the client. Without the ability to guide the client to helpful solutions by drawing on our shared body of knowledge, we ignore this gift and lose precious time. When we consider the best performers in the world, whether in sports or business, it is clear that their success comes from a mix of raw talent, excellent mental state coaching and expert ‘suggestions’.

Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, Chris Morgan is an experienced and trusted executive coach. He is a partner at Morgan Alexander, and co-founder of Listentool, a real-time feedback software solution.

About the Author

Chris Morgan

Founder and Principal

Based in the San Francisco Bay area, Chris Morgan is founding principal of Morgan Alexander, a consulting firm that coaches senior management teams to lead winning organizations, and co-founder of ListenTool. He is one of a few executive coaches with more than 20 years of experience, having started with The Alexander Corporation. Morgan’s clients are primarily CXO engagements with Fortune 500 companies, and high-tech startups in the San Francisco Bay area.