Hope Is Not a Plan: The Myth of American Manufacturing

In building a case for an American manufacturing renaissance, economists cite increasing productivity, cheap natural gas, and rising value-added figures to show that manufacturing is in good shape and will get better. Some of these positivists also claim that rising labor costs in Asia and the creation of U.S. manufacturing jobs since 2010 are evidence of a big turnaround in manufacturing. There are also some mysterious predictions, shared without data to back them up, that manufacturing exports will grow and imports will shrink.

Manufacturing has been battered so badly by China and other Asian countries and by American multinational corporation offshoring that people are desperate for positive news. But the question is, are these stories based on truth or are they just “happy talk”?

For example, the McKinsey Global Institute says growth in manufacturing is right around the corner. It projects that the United States could build on its strengths to boost manufacturing value add by up to 20% over current trends by 2025. This boost, the report adds, won’t bring back “1960s-style mass employment on assembly lines” but could raise GDP by more than $500 million and bring “income growth, new jobs, local investment, and ripple effects across other industries.”

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) resurgence scenario projects the creation of about 3.7 million new manufacturing jobs and a reversal of the manufacturing trade deficit. It also predicts exports will grow significantly faster (8.1% annually) than imports (2.5% annually), reaching a positive trade balance by 2024. Energy-intensive industries like chemicals, plastics, fabricated metals, steel and certain capital goods (computers engines, turbines, power equipment, aerospace equipment and semiconductors) are expected to drive that growth.

If you listen to those who paint these rosy scenarios, you wonder if these companies really have the economic data to prove their projections. I think it is natural to want to give the people who have suffered the most from the decline of manufacturing in the last several decades some kind of hope for the future—but hope is not a plan, and it is going to take more than optimistic projections to make American manufacturing grow.

Having a chance at a real turnaround requires a hard look at the long-term trends and verifiable data, as well as serious policy changes.

Does Manufacturing Really Matter?

At the other end of the spectrum, a second group of economists believe manufacturing is now irrelevant and that U.S. workers will all be working jobs in the service economy. As crazy as this might sound, I found that a fairly large group of economists support the postindustrial service economy idea.

William Strauss, a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, stated that “on average, manufacturing output has been growing 3.1% annually over the past 63 years. Automation has enabled U.S. manufacturers to produce significantly more with fewer workers than they did in previous decades. Today, 177 workers can generate as much output as 1,000 plant employees could produce in 1950. Far from a cause for concern, the dramatic loss in manufacturing jobs should be seen as a key metric of success.”

Strauss under-plays the effect on all workers who lose in this game, and he doesn’t even mention what the loss of manufacturing will do to R& D or exports.

Other economists say that the loss of manufacturing mirrors what happened to agriculture in the 20th century, implying that it is a normal economic correction. But the supporters of the agriculture analogy overlook a key point: When agriculture became automated and required only a tiny percentage of workers to increase output, we may have lost the employment, but we still kept the land and the industry. We are now facing losing entire manufacturing industries, not just the workers.

Economists who believe that a service economy will provide the needed growth for the American economy are simply relying on hope, not facts. The truth is if manufacturing continues to decline, then America will decline. The assumption that a service economy is adequate is a huge gamble which risks living standards, the economy, and in fact, our position as the No. 1 economy in the world.

Assessing manufacturing growth requires looking at 12 vital signs of manufacturing and how they are trending. Together, these signs make the case that American manufacturing is declining in terms of market share and employment but can be saved by policy changes.

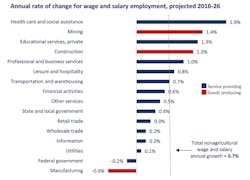

1. Manufacturing jobs – The following chart from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the long-term trend in manufacturing jobs is negative. This chart suggests that we may have a brief rebound but will continue to lose manufacturing jobs in the coming decades. Almost all of the other sectors in the economy (including mining and construction) show growth in new jobs between 2016 and 2026. The Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that manufacturing jobs will go from 12,348,000 jobs in 2016 to 11,611,000 in 2026 – a loss of 736,000 jobs.

2. Advanced training – Politicians are desperate for middle-class jobs that don’t require a college education, and they always point to manufacturing as the answer. But the fact is that most manufacturers don’t want the people who have been laid off. They want multiskilled employees (apprentice/journeyman) who will help them do more with fewer workers.

A recent report called “The Skills Gap in U.S. Manufacturing 2015 and Beyond” projects that with retirements in the next decade, 2 million manufacturing jobs will go unfilled.

This skilled workforce shortage problem is not new. The urgency of the problem was described as far back as 1990 by the National Center on Education and the Economy, with its report "The American Workforce - America’s Choice: High Skills or Low Wages." Since then, the problem has been well-documented, in five more reports: in 2003, 2005, 2007, 2011 and 2015.

It has been at least 25 years since the alarm was sounded on skills shortages in manufacturing and the threat of retiring baby boomers. So, the question is: Are the manufacturers investing in the apprentice/advanced training they say they need?

The proof that it is not happening is in the U.S. Department of Labor database of federally registered apprentices in the U.S. Of 533,607 registered apprentices across all industries in 2017, only 17,559 were in manufacturing.

Training the new manufacturing workers to do advanced troubleshooting and have the multiskill ability to do many jobs, I believe, will require an investment in long-term, comprehensive training programs. McKinsey estimates that a national apprenticeship program could cost $40 billion annually.

But I suspect that the publicly held companies will continue to view training as an expense rather than an investment. This kind of mindset is very suspicious of training programs that take years to complete, paying people for skills they attain, or issuing certificates to people that make their skills transferable.

The federal government has also offered a solution for training people with advanced skills. They propose building 15 Advanced Technology Centers around the country. It is amazing to me that both the federal and state governments always think that building brick and mortar buildings and hiring staff is the answer to training problems.

We need apprentice programs and corporations don’t want to fund them, so wouldn’t the money be better spent funding the wages of apprentices over the many years it takes to certify them as journeymen?

After his election, President Donald Trump promoted the idea of apprenticeship type training, but so far he has declined to commit any significant funding to training.

3. Machine tools – Machine tools are the foundation of manufacturing. They are the master machines that make other machines.

In 1965, U.S. machine tool builders were responsible for 28% of global production. By 1986, that share had declined to less than 10%.

According to the 2016 Gardner Market Research survey, our share of the global machine tool market now stands at 5.8%.

4. Trade deficit – When imports and exports of a country are in balance, all trading countries benefit. Each country specializes in what it does best—exchanging its most competitive products for products it could not produce as cheaply as the trading country. Normally trade deficits are self-correcting, because as the deficit grows, the country’s currency is supposed to decline in price in the world market. This makes exported goods less expensive and foreign goods more expensive, which brings trade into balance.

But this is not happening because we allow our trading partners to manipulate their currencies to always keep the dollar high and force the U.S. to run trade deficits. We then have to finance this deficit by borrowing from the same countries and issuing the government securities as collateral so that we can buy more of their imports and increase our deficit.

An article by the Economic Policy Institute makes a strong case that trade deficits are related to the loss of jobs. It asserts that between 2000 and 2007, 3.6 million manufacturing jobs were lost. After the Great Recession, between 2007 and 2014, another 1.4 million manufacturing jobs were lost. Overall manufacturing lost more than 5 million jobs since year 2000, during a time of increasing trade deficits.

Up until the late ’90s, trade deficits were relatively small, “never exceeding $131 billion annually, and they never exceeded 1.7% of GDP.” After 1998, trade deficits began rising sharply and peaked at $568 billion in 2017. The U.S. now owes $11.15 trillion to the countries that loan us money to finance the deficit. This is not an accounting convention; we really are obligated to pay this money back. Which begs the question: What if a loaning country decides they want their money back and want to cash in the government securities we gave them?

Who are the losers? As I see it, the losers of the ongoing policy of financing trade deficits are American workers, manufacturing, taxpayers, and the economy in general (because trade deficits are added to our federal deficit). Continuing to run trade deficits has led to de-industrialization and the loss of millions of jobs.

Who are the winners? The obvious winners are the multinational corporations who have built plants in Asia and can ship their products back to the U.S. Conservative pundits and lobbyists are always supportive of trade deficits. They make the case that trade deficits are good for the economy, good for consumers, and create jobs.

As more American manufacturers move abroad, the flow of money out of the country will eventually exceed the benefits of cheap imports. In the last five years, the trade deficit grew from $461 billion to $568 billion.

The trade deficit begs two questions. First, if we have to pay the money back, how will we do it with a growing federal deficit? Second, how much can we continue to borrow? We now have a balance of $11.5 trillion. Is it okay to go to $20 trillion?

President Trump has sent out numerous tweets decrying trade deficits. But I haven’t heard of anybody in either political party offering a real plan to begin reducing trade deficit growth or even admit it is not sustainable for the long term. Unless we can set a goal to reduce the trade deficit, there is simply no chance of a manufacturing renaissance or big increases in manufacturing jobs. And I am afraid that the continuous borrowing to finance deficits at some point will overwhelm us.

5. Federal research – Basic research by the federal government differs from private R&D in that federal basic research is high-risk and seldom translates into commercial products in the short term. Private R&D, on the other hand, is driven by shareholders for short-term profits.

Most people are unaware that federal basic research was the initial research that led to the development of many products seen today, including the Google search engine, the internet, GPS, supercomputers, artificial intelligence, smart phone technology, shale gas, seismic imaging, LED technology, MRI, Human Genome Project and advanced prosthetics, to name just a few.

What this demonstrates is that the best strategy for the future that America can employ is innovation, which comes from research—and government-funded basic research is crucial.

In the early 1960s, federal research spending was more than half of the total R&D spending; by 2012, it had fallen to 31% of total R&D. This decline is a very bad trend because this research is the lifeblood of all R&D, and most experts believe that declining basic research will eventually lead to declining GDP growth.

6. Manufacturing’s share of R&D – Manufacturing R&D is vital because it is 70% of all business R&D. Any decline in manufacturing will result in a decline of R&D and our strategy of innovation.

7. Advanced technology products – China has already swallowed the low-tech products we use to make. What they want now is our advanced technology products and all of the new technologies that go with them. The U.S. government-designated Advanced Industries sector includes 50 industries—35 manufacturing, three energy, and 12 service. They are our best shot at maintaining competitive advantage and sustainable economic growth. According to the Brookings Institution, Advanced Industries employ 80% of the nation’s engineers, perform 90% of private sector R&D, generate 85% of U.S. patents, and account for 60% of U.S. exports. These industries employ more than 12 million workers and another 27 million secondary workers for a total of 39 million jobs. America’s Advanced Technology Industries now produce 17% of the U.S. gross product.

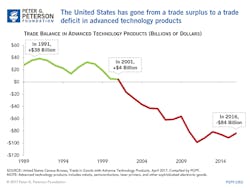

But as important as the Advanced Industries are, there are big problems emerging. Job creation in this category has been stagnant for many years and as the following chart from the Peterson Foundation shows, we have been running trade deficits since 2002. We need to protect the technology of these industries or we simply won’t be able to lead in innovation.

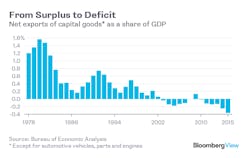

8. Net exports of capital goods as a share of GDP – Trade in capital goods, such as airplanes, medical equipment, semiconductors, etc., are a big part of our exports and have long been a factor of our competitive strength. But as the chart below illustrates, this is no longer true. Capital goods have changed from a surplus to a deficit.

9. Industries lost or in decline – It would seem that the simplest indicator of either growth or decline is the government figures on industries, which are available from the Monthly Labor Review in their employment outlook: 2008 to 2018.

The industries that are essentially lost and probably never coming back include textiles and apparel, semiconductors, coal, cellphones, robots, and luggage.

The industries that are in decline and may eventually die unless they get some protection include furniture, steel, aluminum, autos, computer and peripheral equipment, and motor vehicle parts.

As those industries decline, manufacturing’s share of GDP drops. From 1948 to 2003, manufacturing output increased along with productivity. But from 2000 to 2010, the share of GDP growth began to decline along with manufacturing jobs and overall GDP. In fact, in that decade, manufacturing productivity increased by 66%, while manufacturing jobs declined by 33%. Manufacturing’s percentage of GDP has been declining since 2014.

10. Exports – Manufacturing was a top priority of the Obama administration, which strove to double exports during Obama’s second term. But Robert Scott of the Economic Policy Institute said the U.S. economy fell well short of that goal, as exports only increased by 48.4%. Not only did the U.S. fall short, but the rise in exports between 2009 and 2014 was actually smaller in percentage terms than it was in the five years following the 2001 recession.

Most people do not know that U.S. manufacturing has contributed an average of 70% of American export shipments every year since 2000. But, exports are not growing fast enough to offset the trade deficit. In fact, we are beginning to lose our place as exporter to the world. China has taken over the No. 1 position in world exports. The U.S. exports have fallen to No. 2 and Germany is third and likely to take over the No. 2 position. If increasing the ratio of exports to imports is the only way we can reduce our trade deficit, then manufacturing exports are not only vital, they are the solution to the trade deficit problem.

11. Our strategy of innovation – Just about everybody, liberal or conservative, believes that innovation is the primary strategy America depends on to compete in the global economy. President Obama, in a State of the Union speech, summed up our competitive challenge when he said, “The only durable strength we have—the only one that can withstand these gale winds—is innovation.” But the loss of our technologies through partnerships, unfair trade, technology transfer and espionage has shown that we are fast losing our innovation edge to countries like China. If we can’t stop this ongoing loss of technology or halt the decline of U.S. manufacturing, we will not be able to compete with a strategy of innovation.

12. Manufacturing and national defense – Many industries, like aerospace, high tech, software and others build the products that allow America to have the world’s most powerful arsenal. Basic industries like the chemical, petroleum, mining, and electronics industries are part of our strategic and defensive reserves. Maintaining these industries and the suppliers and skilled workers in them is a matter of national security, yet we are losing ground to foreign manufacturers who manipulate their currencies, have government subsidies, or don’t have to pay the same tariffs they place on foreign imports. For most of the declining industries (despite increasing productivity) it means continuous decline of employment, more imports and the eventual loss of the industry to foreign competitors.

We have exported the manufacturing of many defense components and materials to lower cost foreign producers which has seriously eroded the supply chain that made them.

All of these issues problems are connected. If we are to keep an industrial base and have any hope of growing manufacturing or competing with an innovation strategy, we have to address each of these problems with new policies.

Specifically, we need to:

1. Develop a plan with specific objectives and a timeline to reduce the trade deficit.

2. Increase federal basic research.

3. Offer more incentives to keep jobs in the U.S.

4. Give more government support to the Reshoring Initiative developed by Harry Moser. Reshoring jobs may be the only way to increase manufacturing jobs under the circumstances.

5. Accept that the government is going to have to fund part of apprentice training.

6. Impose value-added taxes and tariffs to stop the decline of industries that are critical to national security, such as machine tools, the advanced technology industries, steel, aluminum, etc.

7. Impose severe penalties to stop the Chinese theft of our advanced technologies, including penalties on multinational corporations giving our technologies to China.

8. Impose sanctions on countries that manipulate their currencies to reduce our manufacturing exports and increase their imports.

9. Make a big investment in upgrading America’s infrastructure. This investment would have done more for improving employment in manufacturing and construction than any other policy decision, but we may have lost this opportunity when Congress voted for (and President Trump supported) a tax cut for corporations that resulted in a $1.5 trillion deficit.

It is time for policy makers to quit voting for the status quo and hoping for a magical turnaround, and instead take action. And supporters of manufacturers must stop believing that growth is right around the corner and look long-term at how to revive an industry on life support.

Michael Collins is the author of The Rise of Inequality and the Decline of the Middle Class. He was a vice president at Columbia Machine in Vancouver, Washington.