Profits are derived from customers via sales and distribution channels. But few organizations validly report profit and loss statements for each customer. What explains this?

First, let’s step back to understand the broader picture of management accounting intended for decision support and analysis. Its primary purpose is this: to generate questions that lead to needed conversations.

A Primer on Cost Accounting

I would like to believe that the reporting of more accurate product and standard service-line cost and profitability information using activity-based costing (ABC) principles is now common. ABC accurately traces expenses into costs with resource and activity drivers and provides cost visibility that is traditionally hidden.

Sadly, many organizations continue to use a single indirect and shared expense “pool” that allocates resource expenses into costs based on a single cost factor, which violates cost accounting’s causality principle. Hence, compared to ABC’s disaggregating a single cost pool into multiple ones and then tracing each pool with an activity cost driver based on a cause-and-effect relationship, the existing costs are flawed and misleading. The products and service-lines are simultaneously over- and under-costing because allocations always have a zero-sum error. It’s baffling how accountants can accept this deficient costing practice when ABC is a better alternative.

But let’s put that observation aside and focus on an increasingly more relevant information need: channel and customer profitability reporting. This includes not just product-related expenses but also the “costs to serve” expenses incurred through sales and distribution channels and by customers.

Why Do Channel and Customer Costs Matter?

In the past, companies focused on developing standard products and standard service lines and then incenting their sales force to push and sell them to existing customers and prospects. But many products or service lines are one-size-fits-all and have become commodity-like. For example, most banks offer similar checking and deposit services.

In addition, today competitors can more quickly replicate a company’s standard products and services. Consequently, the importance of services rises, which results in a shift from product-driven differentiation toward service-driven differentiation to differentiated customer microsegments in order to gain a competitive advantage. That is, as the competitive edge from product advantages is reduced or neutralized, the customer relationship grows in importance.

To complicate matters, suppliers are aware that they have a broad range of high- and low-demand customers. For example, high-demand customers might regularly change delivery schedules, require special treatments, return goods, or frequently phone the customer service help desk. Low-demand customers do none of these things. The extra consumption of expenses from high-demand customers means they are relatively less profitable than you might assume from the sales volume of their purchases.

What this means for the marketing and sales functions is that their objective is no longer solely about increasing market share and growing sales but about growing profitable sales. That requires tracing expenses below the product gross profit margin line, including channel distribution, selling, marketing, and customer service costs to serve.

The crucial challenge is to use ABC beyond calculating valid customer profitability data for decision support. The benefit comes from identifying the profit-lift potential of customers, and then realizing the potential and fulfilling it with smart decisions and actions. Marketing and sales need to view customers as an investment, such as in an individual’s personal stocks and bonds portfolio, rather than as someone or some company to spend money on.

Creating a Customer P&L Financial Statement

Customer profit and loss (P&L) information quantifies what everyone already may have suspected: Customers who purchase roughly the same volume and mix at similar prices aren’t nearly the same when it comes to profit. As I just described, some customers may be more or less profitable based strictly on how demanding their behavior is on a supplier. This information also provides cost visibility and transparency when it comes to the business processes and work activities that cause the higher or lower costs—the cost drivers.

Although customer satisfaction and loyalty are important, a longer-term goal is to increase both customer and corporate profitability. There must always be a balance between managing the level of customer service to earn customer loyalty and the impact it will have on increasing owner and shareholder wealth.

There are two major “layers” of profit margin that should be reported in a company’s P&L:

1. The mix of products and service lines purchased.

2. The non-product “costs to serve” apart from the unique mix of products and service lines purchased.

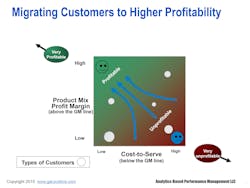

The accompanying graphic (“Migrating Customers to Higher Profitability”) combines these two layers in a two-axis grid: (1) the composite product gross profit margin of the product mix each customer purchases (reflecting net prices to the customer), and (2) their cost to serve. Any individual customer (or grouped cluster) can be located at an intersection where the circle’s diameter size reflects each customer’s revenues. The graphic debunks the myth that customers with the highest sales volume are also generating the highest profits.

The objective is to drive customers with profit-increase potential to the upper-left corner of the grid through a host of actions, such as surcharge pricing, upselling and cross-selling. For example, if a customer purchases a set of golf clubs, can they also be sold a golf shirt? And if they purchase the shirt, can they be sold a second shirt at a discounted price?

The data could also help suppliers identify customers who are substantially unprofitable: those who reside deep in the bottom-right of the grid. These relationships can be terminated through actions such as increased pricing or reduced service-level tactical actions that might encourage customers to “de-select” themselves (i.e., “firing” the customer).

One critical reason for knowing where each customer is located on the profit matrix is to protect your most profitable customers from your competitors. An additional use of this information is to reform the sales force’s incentive compensation bonuses from exclusively 100% on sales to a blend based on both customer sales and profits. This aligns the sales force’s goals with increasing shareholder wealth.

Customer Profitability Reporting Supports Sales and Marketing

The message here is that management accounting helps the sales and marketing functions satisfy shareholder desires. The wide gap between the CFO and sales and marketing needs to be closed!

A company needs to know which types of customers are attractive to retain, grow, win back and acquire—and those who are not. To maximize shareholder wealth, a company also needs to know how much to optimally spend retaining, growing, winning back and acquiring each type of customer. It can unnecessarily spend excessively on loyal customers and therefore destroy shareholder wealth. Or it can spend too little on marginally loyal customers and risk their defection to a competitor. Without this information, financial performance falls short of its full potential.

About the Author

Gary Cokins

Founder and CEO

Gary Cokins is the founder and CEO of Analytics-Based Performance Management LLC at www.garycokins.com located in Cary, North Carolina. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, and author in advanced cost management and performance improvement systems.

After earning an industrial engineering degree from Cornell University in 1971 and an MBA from Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management, Cokins began his career as a financial controller and operations manager with FMC-LinkBelt Corp. For 15 years, he was a consultant at Deloitte, KPMG Peat Marwick, and Electronic Data Systems (EDS), where he headed EDS's Cost Management Consulting Services. He recently concluded a 16-year career with SAS, a leader in business analytics and enterprise performance management software.

He was the lead author of the acclaimed An ABC Manager's Primer (ISBN 0-86641-220-4), sponsored by the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). His Activity-Based Cost Management: An Executive's Guide (ISBN 0-471-44328-X) recently ranked as the best-selling book of 151 titles on the topic. His other books include Activity-Based Cost Management: Making It Work (ISBN 0-7863-0740-4) and Activity-Based Cost Management in Government (ISBN 1-056726-110-8). His latest books are Performance Management: Finding the Missing Pieces to Close the Intelligence Gap (ISBN 0-471-57690-5) and Performance Management: Integrating Strategy Execution, Methodologies, Risk, and Analytics (ISBN 978-0-470-44998-1).

Cokins participates and serves on a number of committees, including the AICPA, CIMA, CAM-I, the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), and the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). He can be reached at [email protected].