Deregulation Under President Trump: Behind the Numbers

The Trump administration is claiming victory in its battle to cut red tape. On Dec. 14th at a White House ceremony, the president announced that in his first eight months in office, covered federal agencies issued just three new rules while taking 67 deregulatory actions (a 1:22 ratio), resulting in annual cost savings of $570 million. He promised even greater cuts in fiscal year 2018 (FY2018). And at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January, President Trump claimed to have “undertaken the most extensive regulatory reduction ever conceived.”

All of this raises some questions: Is the Trump administration significantly reducing the number and cost of federal regulation? Are more regulations being eliminated than are being created? And what does all of this mean for US manufacturers? And for society at large?

Fewer New Regulations under the Trump Administration

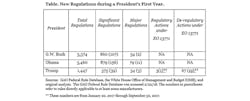

To see what is going on, let’s compare Donald Trump’s first year in office with that of Barack Obama and George W. Bush (see Table). The first takeaway is that there are significantly fewer new federal regulations coming out of the Trump administration than under his predecessors. Whereas the Bush and Obama administrations each issued more than 3,000 federal regulations in their first year, the Trump administration has issued fewer than half that number.

The next column shows the number of “significant” federal regulations. This is the subset of regulations that may have a material impact on the federal budget or the economy, interfere with the action of another federal agency, or raise novel legal or policy issues. Significant rules represent the most contentious rules and in recent years constitute about 25% of all federal regulations. The Trump administration issued 375 significant regulations in its first year, a much lower figure than the 860 and 879 under the Bush and Obama administrations, respectively.

Among significant rules is a subset of “major” regulations. A major regulation is one that will have an economic impact of $100 million or more in a single year—in benefits or costs. It is widely believed that the vast majority of benefits and costs of federal regulation arise from major rules. Here is where the Trump administration is making the biggest difference; just 34 major regulations were issued in its first year, compared to 79 under President Obama and 54 under President Bush. These numbers indicate that the net cost of federal regulation is not decreasing but increasing, and the rate of increase is much less under the Trump administration than under recent previous administrations.

The Regulatory Budget has a Narrow Scope

Interestingly, only a few of these major regulations are subject to President Trump’s Executive Order 1771, which imposed an incremental regulatory budget on federal agencies, the first in US history. Under this order, for fiscal year 2017, the issuance of a new rule must be offset by the elimination of two existing rules, and the net cost of all new rules must not exceed zero.

Soon after the executive order was issued, the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clarified its scope by narrowing its applicability to a subset of rules (significant rules) from a subset of federal agencies (“covered” federal agencies). OMB also created exemptions (for rules under federal benefit programs, for rules related to national security, for rules issued by the Federal Reserve Bank, etc.), which further reduced the scope of the executive order.

OMB also expanded the types of actions that qualify as “de-regulatory actions” to offset the number and cost of these covered new rules. A de-regulatory action need not be a rule; it could be an information collection (e.g., a government survey) or even a guidance document that has no mandatory effect.

Given this change in scope, a total of three regulatory actions and 67 de-regulatory actions were taken from Jan. 21, 2017, through Sept. 30, 2017. However, looking across all regulations from all agencies, the number of new regulatory actions continues to outnumber de-regulatory actions. Because no previous president has instituted a regulatory budget, the number of regulatory and de-regulatory actions under President Trump cannot be easily compared to that of previous administrations.

What about Regulation of Manufacturing?

These numbers, however, tell us little about the impact of the administration’s regulatory reform efforts on manufacturers. To do that, one must identify and compare regulations affecting manufacturers across presidential administrations. The table provides this information in parentheses. With respect to significant regulations, the Trump administration has issued 39 versus 156 under Obama and 107 under Bush. With respect to major regulations, the Trump administration issued a total of three compared to 11 under Obama and two under Bush. One of the Trump major rules was a de-regulatory action (removal of the Obama-era “Fair Pay and Safe Workplace Rule” for federal contractors). These statistics suggest the Trump administration is imposing less cost on manufacturers compared to the Obama administration, but not so different from the Bush administration.

And what about the rules and de-regulatory actions subject to the Trump regulatory budget? It turns out that one of the three new regulatory actions affect manufacturing (DOE energy conservation standards for walk-in coolers), while 19 of the 67 deregulatory actions remove mandates or extend compliance deadlines for at least some manufacturers. These numbers cannot be compared to previous administrations because the regulatory budget concept is a Trump administration innovation; previous administrations did not categorize deregulatory actions in the same way.

Although the Trump administration claims $570 million in annual cost savings during FY2017 under its regulatory budget, this figure does not include monetization of the benefits from new regulatory actions nor benefits foregone from de-regulatory actions. Previous administrations report annually both the costs and benefits of each major rule by fiscal year. Such an accounting is required by law; at some point in the future, OMB will need to submit such a report to Congress for FY2017. Once this is done, the net benefits (benefits minus costs) of the Trump regulatory budget can be discerned. If it turns out that de-regulation has eliminated more benefits than costs, expect a backlash against the administration’s regulatory reform efforts from economists and experts in cost-benefit analysis, who argue that regulation should not be judged on the basis of just one side of the accounting ledger.

What Does the Future Portend?

Based on the performance of the Trump administration thus far, manufacturers can expect that new regulatory burden will remain relatively low. However, it will be very difficult for the administration to reduce existing regulatory burden significantly. Here’s why: (1) compliance cost is often highest when a new rule goes into effect and this sunk cost cannot be clawed back later; (2) it is difficult and time-consuming for a regulatory agency to change an existing regulation that has gone through public notice and comment and survived legal challenge; and (3) there are few major existing regulations in the queue for revision. The Trump administration continues to solicit ideas for reforming regulatory requirements, especially deregulatory actions. If history is any indication, outdated or duplicative requirements have the best chance of being adopted. But even these may take years to undo and will likely be challenged in court.

In the aggregate, the Trump administration is issuing fewer major regulations on manufacturers than that of the Obama administration, and it is seeking to eliminate or delay several major regulations on manufacturers that were issued by the Obama administration. (The difference from the Bush administration is less stark.) The number and cost of new major regulations on manufacturers is likely to remain low, and it is unlikely that the cost of compliance with long-standing regulations will be reduced significantly.

Keith B. Belton is director of the Manufacturing Policy Initiative in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, Bloomington. The Manufacturing Policy Initiative is focused on public policies affecting the competitiveness of the U.S. manufacturing sector.

About the Author

Keith B. Belton

Director, Manufacturing Policy Initiative

Keith B. Belton is principal with Pareto Policy Solutions, LLC, a consulting firm advancing U.S. competitiveness.