The United States has been piling up current-account trade deficits for about 40 years, and it now totals in the trillions (no not billions) of dollars. Economists disagree on whether the deficit represents good or bad news for the nation's economy. So, my question is: Does it really matter whether we have this huge trade deficit, or is it simply an accounting convention that we can ignore?

In my opinion, the answer to this question depends on who you listen to — and who are the winners and losers when the country has a trade deficit.

The idea that trade deficits might be acceptable harkens back to the early days of free-market capitalism and the Chicago School of Economics. Milton Friedman, the original disciple of the free-market school maintained that “a sustained trade deficit is the best possible outcome….we get physical goods like cars, flash memory, oil, computers, toys and all sorts of other goods for cheaply produced paper known as currency.”

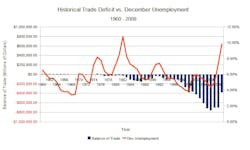

Some economists assert that employment is better when there is a trade deficit. The following graph is a historical depiction showing unemployment as related to trade deficits. The author specifically cites the great depression as a time when unemployment was at its worst and the country ran surpluses every year.

Here are some other examples:

- Mark J. Perry, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and professor of economics and finance at the University of Michigan's Flint campus, argued, in a blog post last year, that "Imports and trade deficits do not ‘hinder’ economic growth and are not a ‘setback’ for the U.S. economy." In the post, he asserts that every voluntary market transaction creates wealth because it benefits both the buyer and the seller. He concludes: “An increase in imports usually means that American consumers are better off (not worse off), U.S. businesses are more competitive (not less competitive), which translates into higher (not lower) standard of living and an increase (not decrease) in the number of jobs.”

- Perry's colleague at the AEI, Derek Scissors, also asserts that trade deficits do not cost America jobs. He suggest that since America has an $83 trillion household net worth we can afford to buy all of the imports that American consumers want, declaring, “Forcing down the trade deficit would mean unhappy consumers, a worse economy, and fewer jobs.”

- The Cato Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington D.C., also puts a positive spin on trade deficits. Daniel Griswold, quoted in a New York Times article says, “The trade deficit is not a problem to be fixed, but a symbol of America’s global economic strength, a Good Housekeeping seal of approval from the World’s investors.”

- The Wall Street Journal editorial page has a similar view of trade deficits. In a recent opinion piece, Trade Deficit Myths, it declares that "running a trade deficit isn’t necessarily bad. In the U.S. it can signal economic health: that American consumers and businesses are saving money buying cheaper foreign goods, and that the U.S. economy is attracting overseas investment, which drives productivity and demand for domestic and imported goods.” They tend to label anybody who is against trade deficits as being protectionist.

- The Republican candidate for President, Donald Trump, has been very outspoken about our trade with China and why it is bad for the U.S. He said, "China is like having a business that continues to lose money every year. Who would do business like that?” The American Enterprise Institute followed up with post, penned by Perry, with the title: “Donald Trump Flunks ECON 101...”

Are these valid arguments?

It is easy to get confused on this subject when it is presented as trade flows, savings rates, productivity growth, and manufacturing output. So I will instead present some common sense questions:

- Is the trade deficit simply an accounting convention that we will never have to pay back?

- Isn’t it dangerous to have our trading partners owning so much of our securities (what if they decide to cash them in)?

- What if China or Japan gets mad at us and don’t want to finance the trade deficit anymore?

- What if the dollar should crash like it has for 21 countries in the last 25 years?

- Why isn’t there a plan suggested by either political party to reduce the trade deficit?

- Who are the winners and losers of trade deficits?

- The trade deficit since 1971 has added up to over $10,096,097,000,000 as of Dec. 2014, according to the U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services -Table 1. How long can we sustain this?

I think the best analogy for the trade deficit is the consumer who piles up $10,000 of credit card debt and pays $10 a month on the balance. For the short term, he is happy purchasing anything he wants, but the balance is growing with fees and interest, and he may never be able to pay it back.

The Other Side of the Trade Deficit Debate

Let me offer an explanation of how trade deficits are supposed to work. When imports and exports of a country are in balance, all trading countries benefit. Each country specializes in what it does best — exchanging its most competitive products for products it could not produce as cheaply as the trading country.

Normally trade deficits are self-correcting, because as the deficit grows the country’s currency is supposed to decline in price in the world market. This makes exported goods less expensive and foreign goods more expensive, which brings trade into balance.

But this is not happening because we allow our trading partners to manipulate their currencies.

Still, trade deficits must be financed. A country simply cannot run a trade deficit unless private or government investors are willing to finance it. To finance the trade deficit, our trading partners (particularly China) loan us the money to pay for the deficit by buying U.S. bonds and other government assets, which enables us to buy more of their imports.

The conservative pundit's are supportive of trade deficits. They make the case that trade deficits are good for the economy, good for consumers, and create jobs. Let’s look at these questions one at a time:

-

GDP GROWTH - Contrary to what the free-trade supporters say, the trade deficit does affect GDP growth. In 2014, our imports were $2,850.5 billion and our exports $2,345.4, leaving a deficit of $505 billion. This subtracted 1.02 percentage point from GDP growth.

-

Federal Deficit – Some people hate the federal deficit but ignore the trade deficit, even though they are related. Trade deficits and surpluses are added to or subtracted from the Federal Deficit. Since we have been running trade deficits since 1971, they are added to the Federal deficit annually, making it worse.

-

Wage growth and living standards - U.S. living standards have fallen for most of the middle class. Since 1967, the median household income has only risen from $42,000 per year to $51,000 per year, a gain of $9,000 in 45 years. The median household income reached a high point of $56,080 in 1999, but has fallen $5,063 to $51,087 in 2012.

The decline of middle-class income also has resulted in the decline of the share of the nation’s total income going to the middle class. The U.S. Census Bureau shows that middle class income reached a high of 54% in 1968 and declined to 45.7% of total income in 2012.

Working people have seen a precipitous decline in living standards and income over the last 40 years. The reasons for this decline in living standards include the growing gap between the rich and poor, the shift to a service economy, weakened bargaining position of workers, corporate decisions to move production overseas, and the trade deficit.

-

Job loss - An article by the Economic Policy Institute makes a strong case that trade deficits are related to the loss of jobs. It asserts that between 2000 and 2007 3.6 million manufacturing jobs were lost. After the Great Recession, between 2007 and 2014, another 1.4 million manufacturing jobs were lost. Overall manufacturing lost about 5 million jobs since year 2000 during a time of increasing trade deficits.

Up until the late 90s, trade deficits were relatively small “never exceeding $131 billion annually, and they never exceeded 1.7% of GDP.” After 1998, trade deficits began rising sharply and peaked at $558.5 billion in 2006 (or 4.1 percent of GDP). In 2014, the trade deficit was still $505 billion. The author of the EPI study concludes “Thus, the growth in the manufacturing trade deficit was responsible for all, or virtually all, of the 3.6 million manufacturing jobs lost between 2000 and 2007.” He concludes that, during the period from 2007 to 2014, the trade deficit accounted for 72% of 1.4 million manufacturing jobs lost.

- Consumer Benefits - One of the rationales for running deficits is the claim of how much the American consumer is saving because of cheap imports. However, when you look at the reduction in household income and the decline of living standards of the middle class, it is obvious that saving on cheap imports has not been enough.

Who are the losers?

As I see it, the losers of the ongoing policy of financing trade deficits are small and midsize businesses, American workers, taxpayers, manufacturing, and the economy in general (America is now debtor nation). Continuing to run trade deficits has led to de-industrialization and the loss of millions of jobs

Who are the winners?

The winners are the multinational American companies and Wall Street who aggressively invest all over the world. By spending a lot of money lobbying they have kept Congress from passing any law that would negate currency manipulation or to develop a plan reduce our trade deficit.

Why Doesn't the Currency Market Correct Trade Imbalances?

An article in the Innovation Files, sponsored by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, asked, “Why didn’t currency markets work the way they were supposed to and force a decline in the value of the dollar?" It's answer: "In part, the answer is because the dollar has been the global reserve currency and therefore maintains its higher value because markets around the world have faith in it. But it has also remained strong because of a refusal from even the most free-market of advocates to support free markets when it comes to currency. This is coupled with economic policies designed to keep the value of the dollar high, which helps savers and financiers, but hurts producers and workers, promoting Wall Street instead of “Industrial Street.”

In macroeconomics there is no free lunch — benefits are always accompanied by costs."

In macroeconomics there is no free lunch — benefits are always accompanied by costs. All of the supporters of trade deficits never talk about whether or how we are going to pay for it. I can’t figure out whether they think we might not ever have to pay for it or if they really don’t care about the long-term and support trade deficits only for the short-term profits they can make. A deficit of $10,096,097,000,000 is a terrible load to put on future generations

I think the trade deficit is unsustainable and very risky. It is like trying to sustain a heroin addiction. The addict likes the high from the injection so much that he rationalizes that somehow he will always come up with the money to buy heroine in the future.

There are several reasons I think the high trade imbalance is unsustainable. The first assumption is that we will always have the foreign creditors that want to lend money to us to finance our debt. Right now, China has accumulated $4 trillion in U.S. government securities. What if they decide to cash them in? Or what if they get mad at us in the future and decide that they don’t want to finance us anymore. Can we get other countries to finance our huge debt quickly enough, or would we have to start paying our way in the world economy?

Another possibility that nobody talks about is a currency crash. In the last 25 years, 21 countries have had their currency crash, which led to hyperinflation. Since the dollar is still the trading currency of the world a similar crash in the U.S. would affect our 88 trading partners, particularly those who have loaned us a lot of money. Hyperinflation would cause the dollar to rapidly lose value (crash) leading to economic chaos.

The U.S. has been running trade deficits since the 70s when the free-market ideology came to dominate. In my opinion, this economic philosophy has led to deindustrialization, loss of jobs, lower GDP growth, declining wages, and an increasing federal deficit. It is very risky for the country, and the multi-national companies and Wall Street are reaping the rewards as Main Street continues to decline.

One idea to bring trade into balance was The Balanced Trade Restoration Act of 2006, sponsored by the late Sen. Byron Dorgan of North Dakota, and supported by Warren Buffet. It would have achieved balance in the foreign trade of the U.S., through a market-based system of tradable certificates and for other purposes. The act would tie other country’s exports to the U.S., to the exports they accept from us. This is a legal method under Article XII of GATT and is part of the World Trade Organization Agreement. The agreement, “permits any member country to restrict the quantity or value of imports in order to safeguard the external financial position and the balance of payments of the member country."

I think we have built a “house of cards” where we have little control, and which could come crashing down on us and our 88 trading partners. We need a plan to begin to balance our trade.