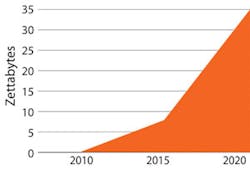

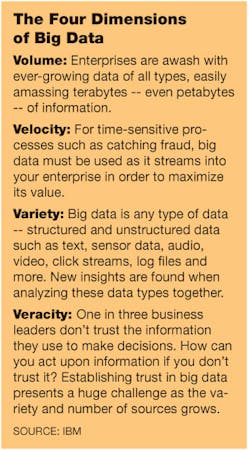

Petabytes and exabytes, zettabytes and yottabytes -- this is the new vocabulary of the digital age. It's an age in which over 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created every day -- an age that requires a whole new lexicon to describe, calling up prefixes usually reserved for counting atoms or stars.

See Also: Manufacturing Industry Technology News & Trends

As IBM figures it, some 90% of the data that exists in the world today was created within the last two years, born from sensors recording every turn of every engine, every tick of every machine, every tweet and every Facebook "like." It is the byproduct of a world in which everything is recorded, everything is searchable and permanent, where no detail, however minute, is missed.

This is the age of information -- the age of big data.

As we enter it, it's clear that neither life nor business will ever be the same. And already, manufacturers who have found the new alchemy of turning data to value are recording record profits and climbing to new heights of productivity.

The Next Big Thing

The big data wave struck the world in 2012, shooting the term to the top of the pop culture buzz list and to the top of the to-do lists for every IT manager in manufacturing. Since then, it has inspired a kind of digital revolution in manufacturing that has savvy, data-driven leaders climbing to the fore. As they do, data is quickly becoming the new currency of capital investment.

"CEOs and CFOs are used to looking at their physical assets, their plants and trucks and buildings, for returns," explains Keith Henry, vice president of global industry solutions, manufacturing at Teradata -- a data warehousing and analytic technology provider.

But focusing on those assets is an outdated mentality, he says. The new way to capital gain is through refocusing on big data and big data analytics and letting them steer the enterprise.

"This is the next great productivity breakthrough," he says. "But it's not going to be easy. It requires a new breed of business leaders in manufacturing brave enough to apply capital to big data and analytics to show the world how it works."

Luckily the industry has just the hero it needs for this task: Rob Schmidt, CIO of business intelligence at Dell (IW 500/20).

Dell's Data-Hungry Leader

Schmidt is a big data geek if ever there was one.

"I'm an IT guy. I love IT," he admits. "And man, if there's data out there, I want it. I want it because I know I can drive value out of it somewhere."

He possesses a techie's genuine appetite for information. But that appetite is tempered by a corporate leader's need for value. The result of that mixture is a data system uniquely arranged to capture and record as much information as possible while simultaneously putting it to work toward capital growth as fast and as efficiently as possible.

That system, based on a Teradata architecture, runs analytics across the company's vast business network from engineered suites by Teradata and SAS, but also through business-oriented programs running through the open-source Hadoop platform.

The result is a complex, custom-fit system that has now run, tracked and processed over 17 trillion transactions. And that is certainBut that part doesn't bother Schmidt.

"The size of the data doesn't matter," he says. "We could record every single point if we really wanted to. That's not the issue."

"The hard part," he explains, "is finding the right data to collect; the hard part is knowing how to apply it to drive the most value."

And that point strikes at the heart of the biggest big data concerns in 2013.

Data, Data Everywhere

"Storing data, recording data is cheap today. It's easy," explains Radhika Subramanian, CEO of analytics solutions provider, Emcien. "Now data is everywhere, everyone has data. It's like dirt."

According to Subramanian, in all the hubbub as the phrase "big data" passed through its hype cycle last year, no one stopped to consider that the data part of big data isn't really such a big deal.

"Data itself is useless," she says. "Nobody really wants more data; nobody wants another chart, another graph. What they want is a system that tells them how to do their jobs better." And that, she says, is the real issue at this point in the evolution of big data. It isn't about getting more data necessarily, the real concern is about driving intelligence from the data you have -- about making that endless supply of information into something actionable, something you can put to work.

"It's about intelligence," she argues. "People need systems that will turn their data into an action that they can go do."

Putting it in Context

"With the proliferation of devices out there bringing us information, we now have the ability to capture more data than ever before at the manufacturing level," says Mike Caliel, president and CEO of global technology giant, Invensys.

"What is critical from there is the ability to contextualize and act on that information in a way that will drive safety and drive reliability in the manufacturing and business processes," he explains.

Invensys Vice President Peter Martin calls this movement the "holy grail" of analytics.

To him, the way we handle data in the manufacturing world should be no different than the way we use it on our smartphones every day.

"You start up Google maps on your phone and it immediately knows where you are. You click a box and it can show you exactly the traffic from here to the airport," he explains. "Hungry? It can pull up restaurants along the way that serve the food you like. It'll show you the menu, find you an open table."

The data behind that functionality -- the ability for the system to pull together your location, preferences, and real time environmental information into a sensible, user-friendly interface -- is just absolutely mind boggling, he says. But it is so commonplace that we don't even think about it anymore.

"Take that back to manufacturing and we have the same situation," he says. "All of that information is available to us, but instead of looking for restaurants and traffic, you're looking for best batch, optimal production run variability, without a lot of custom code or fussing about."

A good system today, he says, "has to show me what's out there, show me the information available, what it means, how to react to it and then help me predict what's coming next," he says. "That's where we're going in the industry."

And that is exactly the vision Schmidt is puzzling out at Dell as he translates the long-standing and battle-worn PC staple into a new analytics-driven powerhouse.

Dell On the Move

Dell is a company in transition.

After dominating the enterprise PC markets for decades, the Texas-based configure-to-order manufacturer is making a definitive move away from the product side of the business and headlong into services and solutions.

Doing so has meant totally restructuring its business model, rethinking even the core configure-to-order option that helped make the company great.

"Historically, Dell has worked with low inventory, at best no inventory," Schmidt explains. "But in our new model, as we move forward over the next couple of years -- and actually coming into effect very quickly -- we are going to sell a significant amount more out of inventory."

This sounds like a manufacturing problem, or at least just a simple business problem. But for Dell, it hits squarely in the data.

Just a few years ago on the Dell website, variations in models, software configurations, memory, screens, design and every other customizable feature resulted in over seven septillion possible configurations of Dell products -- that's 7,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000 possibilities.

Moving to an inventory-based system required trimming a dozen or so zeroes off that range in such a way that the company could still satisfy the diverse needs of its broad customer base. And that meant putting Schmidt's data to work.

To do that, Schmidt and his team, led by Bart Crider, IT director for enterprise BI at Dell, created a new system called "optimized configuration" to help transform the product model.

"The analytical team clustered high-selling configurations from historian order data to create technology roadmaps," Schmidt explains. "They created automated algorithms to identify potential demand coverage for specific configurations -- so the data could tell us what configurations we should be building and what configurations we wanted to put into inventory."

"Basically," Crider adds, "we were able to take all of the historical data from our Teradata warehouse, and run cluster analysis to determine the most common configurations our customers were choosing."

Going through that pile, he says, they were able to trim those seven septillion options down to a couple million, even identifying certain models so common that the company could stock into a preconfigured inventory to sit, ready to ship.

"We targeted the ones that people were most interested in and which they could build within the best margins," Crider says. "We set it up in a system so that, if you order today, I can have it to you tomorrow."

Such a system is dangerous in a typical setting. In the wildly shifting, tumultuous PC market, a warehouse of product is too commonly a warehouse of shrinking value -- unless you have another warehouse of data on the other side backing you up.

But of course the real test is in the results. And, according to Schmidt, this "optimized configuration" experiment passed with an easy A, bringing the company an extra $40 million in positive revenue.

"From a Dell perspective, we fully agree that the rise of big data has a massive amount of value," Schmidt says. "I think a couple of years down the road, we're going to be able to drive faster insights and more value on data to information than we ever imagined possible."

"We're pretty excited about it."

About the Author

Travis M. Hessman

Editor-in-Chief

Travis Hessman is the editor-in-chief and senior content director for IndustryWeek and New Equipment Digest. He began his career as an intern at IndustryWeek in 2001 and later served as IW's technology and innovation editor. Today, he combines his experience as an educator, a writer, and a journalist to help address some of the most significant challenges in the manufacturing industry, with a particular focus on leadership, training, and the technologies of smart manufacturing.