Half of the human population is female. More than half of all university students in the United States are female. Around a third of all MBA students, including those concentrating on supply chain studies, are female. And yet, when SCM World did a manual count of top supply chain executives in Fortune 500 companies, we found only 22 women among 320 businesses that had a true supply chain function. The numbers tell a story of winnowing down a talent pool to the point where nearly all diversity in gender terms is gone by the time careers in supply chain reach their peak. So what?

The problem is not really about fairness, but about value—value for shareholders, customers and society as a whole that could be created with greater gender balance in the increasingly critical supply chain function across industries. Supply chain as a discipline is suddenly crystallizing out of a series of silo functions, including purchasing, manufacturing, distribution and planning.

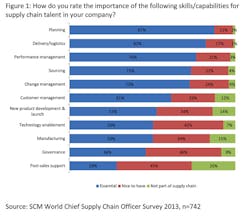

SCM World research on the essential skills required for success in supply chain points to high demand for competence in not only these classic skills but also such softer managerial skills as change management and performance management (Figure 1). Top supply chain executives in 2014 must be both technically proficient in operations management and also savvy as business leaders. Diversity in ability clearly trumps deep, narrow expertise in adding value to business.

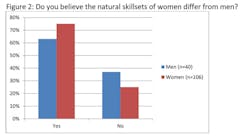

To understand whether the evident lack of gender diversity matters to business results, we surveyed 147 supply chain executives across industries in mid-2013 (Figure 2). The results were telling. Both men and women who responded agreed with the statement that “the natural skillsets of women differ from men.”

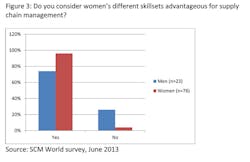

More important, and by an overwhelming majority, both genders also agreed that “women’s different skillsets [are] advantageous for supply chain management.” The near consensus seems to be that the diversity of skills possible with better gender balance in companies’ supply chain functions would be good for business (Figure 3).

A Difference in Skillsets

The obvious question then is how women’s skillsets differ from those of men and where this applies specifically to supply chain. Research on brain science comparing men and women that was conducted by the University of Pennsylvania finds dramatic and distinctive differences in neural pathways (Figure 4). Men, it seems, process information front to back, while women’s neural flows cross back and forth from one hemisphere to the other. The cognitive implications of this are that men are generally better equipped to learn and execute single tasks while women tend to excel at multi-tasking.

Applying this finding to what we know about the fast-evolving supply chain discipline, it seems reasonable to think that the “old-school” asset-centric optimization logic dominant in late 20th century manufacturing and distribution would have favored men. Today, we see far more ambiguity in analytical decision making around business trade-offs made constantly in the modern integrated supply chain. Is it possible that this new environment favors women? Yes it is.

Practitioners’ views on this include a recognition that women as leaders in supply chain often excel in forming, motivating and leveraging teams to get work done. Beth Ford, executive vice president and chief supply chain & operations officer at Land O’Lakes, says, “Women make very strong leaders… a leader will know how to access resources to get the tactical work done.… What do women bring to that? Well, I’ve noted strength in the ability to collaborate, to integrate views, to mentor… the empathy and belief that it’s important to shepherd others’ careers and to be good business partners with a level of humility.” She goes on to note that many men also possess these abilities, but concedes that the perhaps stereotypical female proclivity for shared success lends itself to this kind of leadership behavior.

Regarding the oft-mentioned capacity for multi-tasking, Sandra Wellet, vice president of EMEA supply chain for Lenovo, concurs, “We tend to just get it done… we do really well at multi-tasking.” The interesting thing about this relatively provable skill difference is that it is unfortunately sometimes accompanied by a paradoxical inattention to seeking credit.

Sheryl Sandberg’s much discussed book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, urges women to take credit where it’s due and assume the kinds of leadership roles described above by Beth Ford. From a supply chain perspective, this advice is vital since the function almost always depends on successfully delivering both high service levels and low cost at the same time. Supply chain, by its very nature, is all about multi-tasking, and while this inevitably requires teamwork, it also depends on leadership. Women can, and should, build on this advantage to make their operations more effective and to get ahead professionally.

From a CEO or board-level perspective, the issue must be seen in terms of business value. The dearth of female talent at the top of corporate hierarchies is problematic for the same reason that pure metals are weaker than alloys or monocultures less sustainable than diverse ecosystems—diversity brings strength. Looking ahead to businesses built on emerging economies and new industries, senior leadership teams will undoubtedly need more breadth of perspective to perceive nascent threats and opportunities before it is too late.

The lessons learned in post-apartheid South Africa apply here, as Sandra Kinmont, head of Unilever’s Supply Chain Academy, notes, “I’ve grown up in a country [South Africa] where we didn’t value everyone equally… I’ve seen the value you can bring when you bring real diversity to a workplace.” The world is changing and supply chains must keep pace.

Taking steps to address gender imbalance in supply chain requires action both at the top and bottom of an organization. From the top, active individualized sponsorship of rising female supply chain practitioners is seen as essential to overcome lingering cultural barriers as well as practical challenges attached to family responsibilities. Beth Ford notes that men are often promoted on potential, while women are promoted on results. Top-down sponsorship is needed to change this pattern.

At the bottom, companies looking to bring more women into the talent pipeline need simply to make a point of recruiting to the goal. Nicky McGroarty, head of supply chain at Telefonica UK, for instance, says recruiting inbound equality is key to success. Some, including Sandra Wellet at Lenovo, reluctantly concede that quotas may even be needed to begin reversing the established trend.

The value of diversity in supply chain talent is still just an inference, but opinions in the profession clearly point to some belief that it is a fact. It is certainly true that supply chain leaders need a more diverse set of skills today than in years past and that women, while still under-represented, are sought by organizations looking to improve performance. Making change, however, will require more than just a commitment to fairness. Concerted effort will be needed to recruit, develop and promote women in supply chain if the value of this added diversity is to be captured.

Kevin O’Marah is chief content officer with SCM World.