The Politics of Outsourcing

I have spent most of my career involved with “manufacturing jobs,” “outsourcing,” “offshoring,” and “globalization,” so I pay a lot of attention to the political discourse on these topics. Recently, the U.S. presidential race has gotten tied up in the debate about outsourcing and offshoring of manufacturing jobs, so it seems like a good opportunity to share some professional insight with Mr. Governor and Mr. President.

First of all, why did we get so enthralled by manufacturing jobs? A new national poll by the Alliance for American Manufacturing finds that 53% of American voters believe that manufacturing is the industry “most important to the overall strength of the American economy,” and 89% favor a national strategy to support manufacturing in the U.S.

The candidates are equally concerned. President Obama has issued a “Blueprint for an America Built to Last,” which is intended to encourage companies to create manufacturing jobs in the United States. Governor Romney has promised to issue an executive order to sanction China for unfair trade practices on his first day in office.

My first thought is, “Clearly, none of these people has ever actually worked in a manufacturing plant.” My first job out of college was working in a plastic bottle manufacturing plant in Houston, where it hits 100 degrees and 10,000% humidity. The plant was not air conditioned and we worked next to 400 degree extruders. When we had a problem with condensation on the molds, they built enclosures around the equipment and they air conditioned the machines. Not the people, the machines. Welcome to your manufacturing career!

And those manufacturing jobs you want back from China? I’ve been to the Foxconn Longhua plant in Shenzhen, where they put up nets to keep people from jumping off the buildings out of despair. Most of these jobs are repetitive, low skill, low pay, with little opportunity for advancement. If this is what we want for our children, then I’ll stop putting money in my 529 right now.

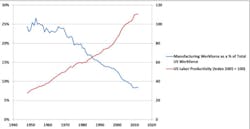

But manufacturing is the heart of our economy, right? Well, no. According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, post-war manufacturing employment, which as a percent of total U.S. employment peaked at only 27% of the workforce in 1953, has for the most part been steadily dropping since, to a current level of 8.4%. This is a trend that is decades old – before Obamacare or Bain Capital; before “outsourcing” existed as a term; before “Japan Inc.” or NAFTA, or any other scapegoat we hear about.

Nothing Magical About a Manufacturing Job

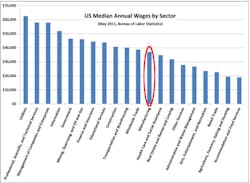

My point is not that people shouldn’t work in manufacturing, or that the United States should never encourage domestic manufacturing – my point is that there is nothing magical about a manufacturing job that makes it a particularly better career than being a cashier or a construction worker or a medical tech or many other jobs. In many ways, manufacturing jobs can be more difficult, lower paid and less glamorous than other options.

What I don’t understand is why we aren’t talking about farm jobs! That’s right, farm jobs. In 1900, 41% of the American workforce was employed in agriculture, according to the USDA. That’s way more than manufacturing ever was. By 2000, the percentage of the workforce in agriculture was down to 1.9%. Just imagine the millions of jobs we could create if we had an American Agricultural Renaissance!

Does it sound silly to want to revert to the economy of 1900? Is reverting to 1953 much less silly? What has happened to manufacturing is very similar to what happened to agriculture: We had huge increases in productivity, meaning we could make the same output with fewer people. Concurrently, we have had a growth in the workforce as a whole and a growth in other industries, so the resulting fractions of workers in agriculture and manufacturing have dropped. It’s the advancement of technology and the evolution of the economy, not any decline in American greatness.

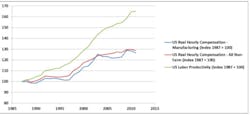

Americans are rightfully concerned about opportunity, but there is no silver bullet to be found in manufacturing. A job at the plant used to represent a way for a blue collar worker without a college education to have a middle class life, benefits, and retirement, and Americans still want that opportunity. If not manufacturing, then what are those jobs today? Real wages in the United States have not kept pace with productivity, meaning the average worker is not sharing in as much of the gains of the economy. This is a broader trend in the economy that includes manufacturing, but is not unique to it. I would like to hear our candidates address this trend and give a vision for career opportunity that doesn’t require a time machine to the 1950s.

Are Outsourcing and Offshoring Evil?

How about outsourcing? We all know that’s bad. Eighty-three percent of those surveyed by the Alliance for American Manufacturing had an unfavorable view of companies that outsource jobs to China. I’m sure they completed that survey on their iPads. Google recently announced that it is assembling its Nexus Q media device in the US. They say that building in the United States is not cheaper, so I suppose the only reason to do it is so they can fulfill their motto, “Don’t be evil.”

The candidates seem to be falling over themselves to condemn or distance themselves from “outsourcing.” The Obama campaign doesn’t quite know the difference between outsourcing (buying from another company a product or service which you used to do in-house) and off-shoring (moving production from the United States to another country). The Romney campaign would have us believe that he really didn’t run Bain when they did off-shoring, he was just CEO. Romney should probably avoid talk of “off-shoring” in any case because it sounds too much like what you do with your cash when you have an account in the Cayman Islands.

I have to say I am professionally offended by the name calling related to outsourcing. I mean, “Outsourcer in Chief”? Please, Mr. President – Mitt Romney and Bain Capital are nobodies in the real world of outsourcing. I have probably personally presided over more business transfers to China than Bain Capital ever did. I should get the title Outsourcer in Chief before he does. He hardly qualifies as Assistant Deputy Under-Secretary of Outsourcing in my professional circles.

And in my profession, outsourcing and off-shoring are no more “evil” than any other rational economic decision. The hard truth is that some economic decisions result in fewer workers at an individual firm, even while they benefit the economy (and therefore, the total number of jobs) as a whole. Automation, “Lean” manufacturing, and other productivity improvements or technology changes can affect jobs just as easily as outsourcing can. It would be great if we heard more from the candidates about how we can help people who lose their jobs – for whatever reason – stay on their feet, get retrained and get rehired somewhere else in the economy; and hear less blame assigned to individual companies.

The right way to think of off-shoring and international trade in general is as a form of technology. Imagine an entrepreneur who invents a fully automated process to make solar panels from wheat. He would be hailed as a great American success! Cheap solar panels would be available to everyone! Maybe Obama would give him a $500 million loan guarantee. Romney would undoubtedly call the inventor a “job creator” – never mind all the jobs that would be lost in traditional solar panel factories. Then imagine that you get to tour the factory, and you find that that his “invention” merely involves shipping wheat to Asia in exchange for solar panels. He’s a fraud! A job killer! He’s… He’s… (cover the children’s ears) an Outsourcer!

The cost and benefits of international trade are essentially equivalent to the magical wheat-into-solar-panel machine. We just use different technology. The technology that we use to enable outsourcing includes modern telecommunications, information systems, transportation, logistics, planning techniques, contracts, legal frameworks, etc. Fifty years ago we couldn’t outsource in the same way we do now because there was no ERP, WWW, DHL or WTO.

Drawing the Boundaries of a Firm

But isn’t manufacturing special? There are network effects with manufacturing centers – once you get a concentration of one industry in one place, it becomes more efficient for the industry to grow in that same location. So we should encourage domestic manufacturing so we establish those industries in the United States, right?

Yes, there are network effects in manufacturing, as evidenced by the concentration of consumer electronics manufacturing in south China, or semiconductors in Taiwan, for example. The mistake in the logic is to suggest that having the manufacturing is the same thing as having the industry. One of the great changes in the 21stcentury value chain is the dissociation between the centers of innovation and the centers of manufacturing. The technology of outsourcing allows companies to draw the boundaries of the firm in a different way. High value, differentiated activities can be separated from lower value, commoditized activities.

If you look on the back of your iPhone, it says “Designed by Apple in California”. The things that make the iPhone special – the industrial design, the user interface, the app store – are created mostly in the United States. It’s easy to find a knock-off iPhone in China that looks like an iPhone because it was manufactured in almost the same way, but it takes the Apple employees in California to make a real iPhone really valuable. Those are the high paying jobs we want in the United States, and having the manufacturing in the United States does not mean we get the engineers, programmers, designers and managers that make a company like Apple so valuable. So if we want to encourage science, engineering, R&D, innovation and industry clusters, then we can do that, but that does not necessarily equate to on-shore manufacturing.

The path the U.S. economy has followed, from agricultural to industrial to information age, is the path that China is on right now. The Chinese study the U.S. history of economic development and want to be more like us. They are eager to use manufacturing as a means to raise former agricultural workers into the middle class, build the energy and transportation infrastructure that we take for granted, and then focus the country’s investments in more advanced technology. We in the United States should keep moving forward, not look backward.

I hope our candidates are listening.