The 21st Century has been unkind to U.S. manufacturing workers. In January 2000, there were 17.2 million Americans employed in manufacturing. In January 2016, there were 12.3 million, a workforce about 1.5 million smaller than when the U.S. entered the Great Recession in December 2007. And the questions that have been gnawing at Americans are: Can we do anything about this? And if so, what?

There is a large and well-respected camp that says, in essence, accept the tide of history. Representing this camp, former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich wrote in Forbes in May 2009: “We should stop pining after the days when millions of Americans stood along assembly lines and continuously bolted, fit, soldered or clamped what went by. Those days are over.”

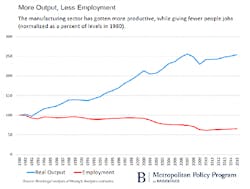

Reich’s essay, “Manufacturing Jobs Are Never Coming Back," did not proclaim that U.S. manufacturing is dead but it did make the case that many of the jobs that Americans had lost in the past two decades were gone for good. The culprit, said Reich, was “higher productivity.” Automation and increasing amounts of computer-aided analysis were reducing the number of “routine” jobs.

While “sometimes we need to consider what’s good for our economy and society as a whole regardless of where the market may lead us,” Reich wrote that the answer was not a larger manufacturing sector in the U.S.

“Creating and sustaining it would be very costly to American consumers and taxpayers. I just don’t get how those costs could possibly be justified,” Reich concluded.

Wait a minute, says another camp. We’ve been shooting ourselves in the foot for decades. If the U.S. puts the right policies in place, we can add millions to the manufacturing sector’s payroll.

“We will make America the best place in the world to start a business, hire workers, and open a factory,” then candidate Donald Trump told an audience on June 28 at an aluminum recycling plant outside Pittsburgh.

We will make America the best place in the world to start a business, hire workers, and open a factory."—President-Elect Donald J. Trump

For Trump, the reason for the slide in U.S. manufacturing jobs was not modernized factories that needed fewer workers. It was a disastrous economic cocktail of high corporate taxes, overregulation and crumbling infrastructure. Most importantly, it was globalization and trade deals such as NAFTA that had promoted international development at the expense of American communities and workers.

“We allowed foreign countries to subsidize their goods, devalue their currencies, violate their agreements, and cheat in every way imaginable. Trillions of our dollars and millions of our jobs flowed overseas as a result,” Trump said on that campaign stop and dozens of others.

That message resonated with millions of voters who had seen their stable, well-paying manufacturing jobs disappear and their communities gutted when they were unable to attract new businesses to replace shuttered factories. For these workers, manufacturing in the U.S. was all but dead and they were angry and scared about it. That simmering discontent helped turn traditional blue states red and make Donald Trump, once the unlikeliest of blue collar heroes, the 45th President of the United States.

Attention now turns to whether President-Elect Trump can come through on his campaign promises to galvanize manufacturing job creation. If he does, he will have achieved something his predecessor was unable to do. Barack Obama spent much of his presidency stressing the importance of manufacturing. While running for re-election in 2012, he set a goal for his second term of filling 1 million manufacturing jobs. To date, according to the Alliance for American Manufacturing, only 298,000 jobs in manufacturing have been created in the past four years.

That effort to create manufacturing jobs was to be fueled by Obama’s plan to double U.S exports, first expressed in his State of the Union speech in January 2010 and then in his 2012 re-election bid. He said achieving that goal would “support two million jobs in America.” Manufacturing, which accounts for more than $1.4 trillion in exports annually, contributes more than half of the nation’s exports in goods and would presumably add significant jobs as exports soared.

That goal is “stalled,” according to PolitiFact. U.S. exporters have been faced with weakened economies around the world and a strong U.S. dollar that has made American goods more expensive for foreign buyers. To meet Obama’s goal, U.S. exports needed to grow from $2.2 trillion in 2012 to $4.4 trillion in 2017. But exports in 2015 were just 1.9% higher ($2.26 trillion) than they had been in 2012.

The Formula for More Manufacturing Jobs

Robert Reich isn’t the only one skeptical of seeing U.S. employers hiring millions of new workers. In an April 26 New York Times article, “The Mirage of a Return to Manufacturing Greatness,” Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitiz observes, “Global employment in manufacturing is going down because productivity increases are exceeding increases in demand for manufactured products by a significant amount.” He concludes, “The likelihood that we will get a manufacturing recovery is close to nil…We are more likely to have a smaller share of a shrinking pie.”

Trump's goal to add millions of jobs is made more difficult by the fact that the U.S. "is already producing a lot" and doing it without adding huge numbers of jobs, says Mark Muro of the Brookings Institution in a recent article. The "total inflation-adjusted output of the U.S. manufacturing sector is now higher than it has ever been," he notes, a result of the "automated, hyper-efficient shop floors of modern manufacturing."

NAM and Trump agree on two major issues to propel manufacturing: regulatory reform and infrastructure investment. NAM has long complained that the regulatory system in the United States is overly burdensome. In particular, the manufacturing organization has complained that EPA has promulgated expensive regulations such as the Clean Power Plan and the Waters of the United States rule, which it says fail to provide sufficient benefits compared to their costs.

During his campaign, Trump said he would eliminate both rules. He also promised a moratorium on new regulations, cancelation of a number of Obama executive orders and a reform of the “entire regulatory code to ensure that we keep jobs and wealth in America.”

Infrastructure spending would also get a big boost if NAM gets its way. Calling the nation’s infrastructure “an embarrassment,” NAM President and CEO Jay Timmons in October announced an initiative, “Building to Win,” which recommended more than $1 trillion be spent on “roads and bridges in disrepair and ports and airports operating beyond capacity.”

“America’s infrastructure is vital to the future of manufacturing in America—to acquire materials for game-changing products, to get our employees to work and to transport what we make to consumers in our country and around the world,” he said.

The president-elect has campaigned to refocus government spending on infrastructure and in the process create “thousands of new jobs in construction, steel manufacturing, and other sectors to build the transportation, water, telecommunications and energy infrastructure needed to enable new economic development in the U.S., all of which will generate new tax revenues.”

And speaking of taxes, both NAM and Trump want to see the corporate tax rate lowered. NAM has proposed shrinking the rate from 35% to 25% or lower. Trump has called for a 15% tax rate. Both also want the U.S. to move to a territorial tax system. Trump has proposed that corporate profits held offshore, which he has estimated as high as $5 trillion, be repatriated at a one-time tax rate of 10%.

Challenging Trade Orthodoxy

While they agree on plenty of issues, NAM and Trump are miles apart on trade. NAM and many other business groups have been staunch supporters of NAFTA and have complained that the U.S. badly needs to ratify new trade agreements such as the Trans Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-Tip).

For his part, Trump has flayed NAFTA as “the worst trade deal in history” and roundly criticized the Clintons for allowing China to enter the World Trade Organization and then stand by while “China cheated on its currency, added another trillion dollars to our trade deficits, and stole hundreds of billions of dollars in our intellectual property.”

Timmons told IndustryWeek that the current protectionist sentiment demonstrates that NAM and its allies “have done a very poor job at educating the general public about the benefits of trade.” He said business groups needed to educate the public on the investments and jobs that trade creates in the U.S. Timmons said NAM was eager to work with the Trump team to identify areas of concern in TPP and NAFTA and determine “how we could be helpful in correcting any of those concerns.”

Timmons pointed to the vast global market outside the U.S. and warned, “Either we make the stuff that gets sold to them here in this country or other countries make the stuff that gets sold to them.”

But trade critics such as Robert Scott of the Economic Policy Institute say the U.S. needs to take a much tougher stance toward enforcement of its existing trade agreements and combating currency manipulation. In a paper published in 2014, Scott said currency manipulation was the “primary cause” of the nation’s enormous trade deficit. In 2015, the deficit in goods alone was $762.5 billion.

Scott said eliminating currency manipulation over a three-year period would reduce the trade deficit by $200 billion to $500 billion and create 2.3 million to 5.8 million jobs, 40% of which would be in manufacturing. That would mean an increase in the most optimistic range of the estimate of 2.3 million manufacturing jobs.

Some trade critics believe Trump must take a broom to the Washington trade establishment if he is going to effect real change. The incoming administration should “clean house of all the academically trained, free-trade economists, bureaucrats, and negotiators inhabiting the trade functions of the federal government,” says Kevin Kearns, president of the U.S. Business and Industry Council. “Trump has called them stupid; they are in the sense that they keep following the same free-trade template, making the same erroneous assumptions in their models, and piling up the same massive goods trade deficits. Yet they expect the next free trade agreement to turn out to be more beneficial to the United States than the last disaster.”

Kearns’ policy recommendations also include having a “concerted national manufacturing strategy,” keeping the U.S. dollar “continuously competitive” and assessing a value-added tax of 15% to 20% on all imports.

“Over 150 of our trading partners use such taxes to make American exports pricier in their home markets,” said Kearns. “We should reciprocate. The great irony is that as succeeding rounds of trade talks have successfully cut tariffs, our trading partners have raised their VAT taxes in response, thus offsetting the tariff cuts. This is a place our trade negotiators have truly been asleep at the switch.”

Manufacturing vs Manufacturing Jobs

While it is easy to understand why jobs were the focus of the presidential campaign, many industry experts are quick to make the distinction between manufacturing production and the growth of jobs.

At a manufacturing conference in Washington, Jason Miller, an Obama economic advisor, noted that manufacturing had been growing steadily after the Great Recession, but during the last 18 months, job growth in manufacturing stalled and production slowed.

Miller attributed the slowdown to several factors. The economies of trading partners in Europe, South America and other regions had slowed, resulting in fewer exports from the U.S. The dip in oil prices had a ripple effect through the economy, resulting in a substantial investment decline.

But U.S. manufacturers enjoy some fundamental advantages, noted Miller. Energy costs are lower than in many competing nations. And the convergence of technologies that has created the Internet of Things is a distinct advantage for the U.S., he said, with America enjoying an “enormous lead in software.” The U.S. also has an entrepreneurial culture with a philosophy of trying things, if unsuccessful failing fast and then moving on.

“The idea that we have been ‘losing in manufacturing’ is actually just flat wrong,” says Justin Rose, a Chicago-based partner with Boston Consulting Group. He said it was unclear whether there will be a net gain in jobs as U.S. manufacturers invest in advanced technologies and require new types of jobs such as data scientists, but he said it was vital for American productivity that they do so.

“Our view for companies and for countries is that they should be aggressive in using these new tools because it is the ones that are bold in adopting them and driving them that will have the biggest competitiveness gain,” said Rose. The “risk of inaction,” he said, is that their competitiveness simply deteriorates over time.

While U.S. manufacturing is not in dire shape, says Willy Shih, a professor at Harvard Business School and manufacturing expert, U.S. industry is changing because of globalization.

“It used to be that if you were an automaker, all your component suppliers were clustered around you in Michigan, Indiana or Ohio,” he said. “Increasingly we’re seeing more content come from abroad – Mexico, Asia, Europe.” Fueling that shift, he says, is that electronics are becoming more important in vehicles.

Using tariffs to draw manufacturing of these components back to the U.S. won’t work for electronics, says Shih, because “We don’t have the supply chain. We don’t make the components.” Establishing a domestic supply chain would take many years and cost billions of dollars.

In Shih’s view, it will be more productive if the U.S. focuses on strengthening its existing industries rather than trying to create or recreate new ones. Trump’s plans to spend more on defense, for example, could help with what Shih sees as a problem for manufacturers – lower defense spending in recent years. He notes that defense has spent heavily on aerospace, space systems, communications and other advanced technologies.

“That has been very beneficial for U.S. industry,” he says, adding, “Now you see the Chinese ramping up military spending in a big way and that is going to drive a lot of their manufacturing infrastructure, too.”

While it is too early for anyone to have any certainty about projecting a Trump administration’s success or lack thereof, forecasters are taking a cautious approach. Oxford Economics noted that the initial reaction of the business community to Trump’s election was generally upbeat but cautioned that “while lower taxes, more infrastructure spending and reduced regulation may be positives for businesses, increased policy uncertainty, more trade protectionism, congressional fiscal orthodoxy and stricter immigration are important constraints.”

The economic forecasting firm’s baseline view: “While private sector activity benefits from lower taxes and increased infrastructure investment in the near term, trade protectionism and elevated policy uncertainty constrain growth to just 2% in 2017 and 1.8% in 2018. The Fed still raises rates in December, but only proceeds with one rate hike in 2017.”

That cautious outlook has been echoed by many manufacturers, who have been reluctant to make major investments given so much uncertainty and tepid growth. NAM’s Timmons says that won’t change until they see “the legislative and executive branches work together to really get things done on behalf of American business.”

About the Author

Steve Minter

Steve Minter, Executive Editor

Focus: Leadership, Global Economy, Energy

Call: 216-931-9281

Follow on Twitter: @SgMinterIW

An award-winning editor, Executive Editor Steve Minter covers leadership, global economic and trade issues and energy, tackling subject matter ranging from CEO profiles and leadership theories to economic trends and energy policy. As well, he supervises content development for editorial products including the magazine, IndustryWeek.com, research and information products, and conferences.

Before joining the IW staff, Steve was publisher and editorial director of Penton Media’s EHS Today, where he was instrumental in the development of the Champions of Safety and America’s Safest Companies recognition programs.

Steve received his B.A. in English from Oberlin College. He is married and has two adult children.